Translate this page into:

Vasopressin-Induced Ventricular Arrhythmia

Soma Sekhar Ghanta, MD, DM Department of Cardiology Aayush Hospital, Vijayawada, Andhra Pradesh India somasekharghanta1978@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Long QT and ventricular tachyarrhythmias can occur due to a number of causes including dyselectrolytemia, drugs, and intracranial lesions, predominantly subarachnoid hemorrhage. Here the authors report a rare case of acquired long QT with R on T ventricular ectopics due to vasopressin in the setting of intracerebral bleed, which reverted on withdrawal of vasopressin.

Keywords

long QT

vasopressin-induced long QT

vasopressin-induced ventricular ectopics

drug-induced long QT

Introduction

Vasopressin is used to manage anti-diuretic hormone deficiency. It has off-label uses and is used in the treatment of vasodilatory shock or gastrointestinal bleeding. Vasopressin is used to treat diabetes insipidus related to low levels of antidiuretic hormone.

The most common side effects during treatment with vasopressin are dizziness, angina, abdominal cramps, and water intoxication. The most severe adverse reactions are myocardial infarction and hypersensitivity. Acquired long QT and Torsades de pointes is seen in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Here, we report a case of drug induced QT prolongation and arrhythmia in setting of intracranial bleed which reversed on discontinuation of drug.

Case Report

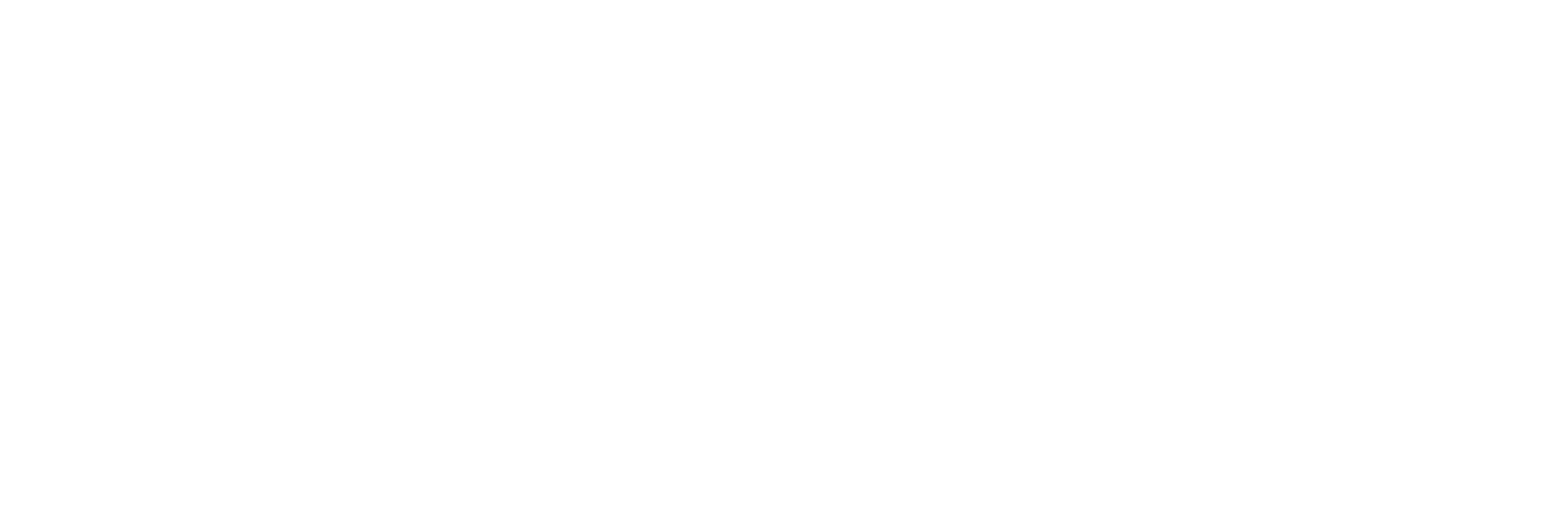

A 45-year-old man presented to our hospital with acuteonset hemiparesis. Computed tomographic (CT) imaging of the brain revealed intracerebral bleed with mass effect. His bedside cardiac evaluation including 12-lead electrocardiogram (Fig. 1a) and transthoracic echocardiography was normal at presentation. On progressive deterioration of neurologic status, the patient underwent emergency craniotomy with improvement in neurologic status. During postoperative recovery period, the patient developed hypotension with normal cardiac function. Other causes of hypotension including sepsis and other sources of bleeding were ruled out and the patient was started on vasopressin. He was noticed to have ventricular arrhythmias manifesting as prolonged repolarization with R on T ventricular ectopics (Fig. 1b). His neurologic status and serum electrolytes including sodium, potassium, calcium, and magnesium were in normal range, and other causes of QT prolongation including drugs and dyselectrolytemia were ruled out. Vasopressin is discontinued with normalization of QT interval and disappearance of ectopics (Fig. 1d).

-

Fig. 1 (a) Baseline ECG showing sinus rhythm with normal QT interval. (b) ECG showing prolonged QT interval with R on T ectopics after initiation of vasopressin. (c) Prolonged QT interval with decrease in frequency of ectopics. (d) Resolution of normal QT interval on day 2 after withdrawal of vasopressin.

Fig. 1 (a) Baseline ECG showing sinus rhythm with normal QT interval. (b) ECG showing prolonged QT interval with R on T ectopics after initiation of vasopressin. (c) Prolonged QT interval with decrease in frequency of ectopics. (d) Resolution of normal QT interval on day 2 after withdrawal of vasopressin.

Discussion

Electrocardiographic (ECG) changes are commonly seen in neurologic disorders, especially in subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). ECG changes commonly seen in SAH are sinus bradycardia,1 tachycardia, atrial ectopics, repolarization abnormalities seen as ST-T changes, prolonged QT intervals, prominent U waves, R on T ectopics, and life-threatening torsades de pointes. These ECG changes are misinterpreted, causing delay in neurointervention and also inappropriately treated as acute coronary syndrome. Long QT and torsades in setting of neurologic disorders are primarily neural-mediated mechanisms. Factors that influence the development of arrhythmias include cerebral vasospasm,2 hypoxia, electrolyte imbalance, and sudden increase in intracranial pressure triggering a sympathetic or vagal discharge due to compression of brain structures.

Common causes of long QT and ventricular ectopics in the setting of intracranial bleed in addition to neural mechanisms are dyselectrolytemia and drugs. Ventricular arrhythmias are seen in SAH patients, more so if they have both prolonged QT and hypokalemia.1

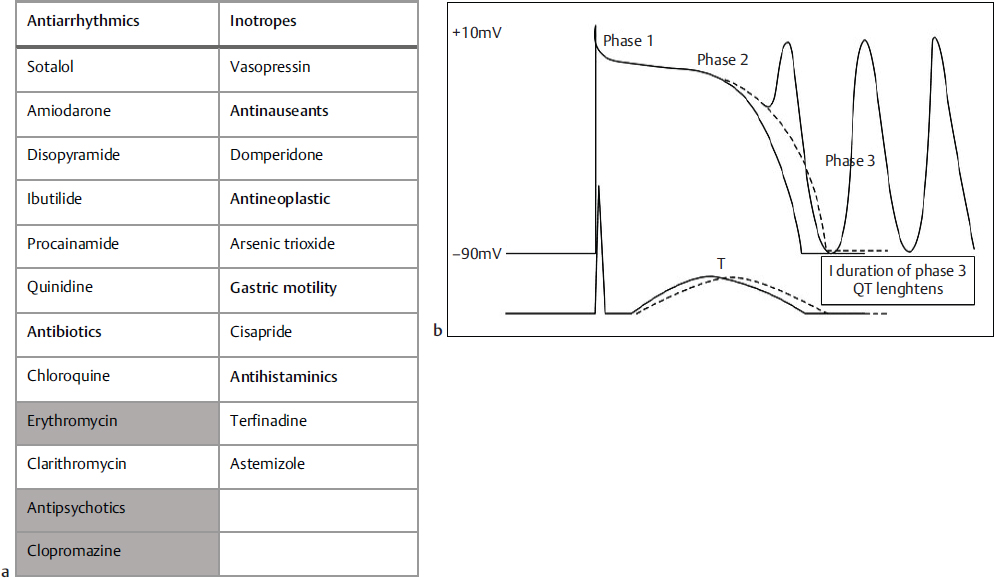

Drug-induced long QT3 4 is commonly seen (Fig. 2a) and can cause torsades increasing mortality in hospital scenario. Many drugs including vasopressin can cause prolongation of repolarization and refractory period by blocking iKr, iKs channels leading to prolongation of phase 3 action potential, and early after depolarizations (Fig. 2b) due to activation of Na+-K+ pump and ICa channel triggering ectopics, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (VT), and torsades. Some of these patients can be silent carriers of long QT genetic mutations5 who manifest arrhythmia precipitated by drugs or dyselectrolytemia. Here in our case either long QT or ectopics may not be due to intracranial bleed as initial ECG is normal and abnormality starts after vasopressin infusion,6 and it is manifestation of drug itself or bradycardia due to baro receptor reflex by increasing blood pressure causing prolongation of QT and R on T ectopics. Polypharmacy,4 dyselectrolytemia, and bradycardia are the common causes of long QT and ventricular tachyarrhythmia in patients with or without silent long QT. Prompt recognition of the event, withdrawal of precipitating factors, and treatment of arrhythmia are required to avoid mortality. Recognizing underlying genetic abnormality and counseling is required for family members.

-

Fig. 2 (a) Table showing commonly used drugs causing long QT. (b) Figure showing how prolonged QTc can cause early after depolarization.

Fig. 2 (a) Table showing commonly used drugs causing long QT. (b) Figure showing how prolonged QTc can cause early after depolarization.

Conclusion

Long QT and ventricular ectopics are commonly seen in patients with intracranial bleed.

Predominantly they occur due to neurogenic mechanisms and dyselectrolytemia. However, drugs that are used in treatment such as vasopressin can rarely cause QT prolongation precipitating life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. Prompt recognition and withdrawal of drug are important and lifesaving.

References

- Holter detection of cardiac arrhythmias in intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage. Am J Cardiol. 1987;59(06):596-600.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrocardiographic abnormalities in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Am J Crit Care. 2002;11(01):48-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Poly pharmacy-induced long-QT syndrome and torsades de pointes: a case report. J Pharma Care Health Sys. 2017;4:174.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanisms, risk factors, and management of acquired long QT syndrome: a comprehensive review. Sci World J. 2012;2012(12):212178.

- [Google Scholar]

- Drug induced QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. Heart. 2003;89(11):1363-1372.

- [Google Scholar]