Translate this page into:

Gender-wise Long-term Predictors for Major Adverse Cardiac Events Following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in the Elderly Population

V. Satish Kumar Rao, MD DTCD Department of Cardiology, Nizam Institute of Medical Sciences Hyderabad, Telangana 500 082 India drsatishrao09@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Background We aimed to recognize the predictors of long-term major adverse cardiac events (MACE) in the elderly candidates for elective percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in relation to gender at our center.

Methods In this retrospective cohort study, we reviewed the data of the elderly patients (age ≥70 years) who underwent elective PCI who met our study criteria in our institution during 2008 and 2018. Demographical data, clinical history, angiographic details, PCI procedure, and follow-up data of the patients enrolled in the study were studied by using the angiographic and PCI procedure details. Patients were characterized in the study group as those with or without MACE, which were then compared and analyzed using the statistical analysis in a univariable and binary linear regression analysis.

Results A total of 355 elderly patients (older than 70 years) undergoing elective PCI were selected who fulfilled the inclusion criteria; 277 patients were men and had more comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, history of heart failure, previous coronary artery bypass graft, and presentation with acute coronary syndrome. MACE occurred in 24 events patients of whom 20 were suffering from DM. Binary logistic regression showed that the only determinant for the 1-year follow-up outcome is diabetes (p = 0.000). Even in univariate analysis, DM (0.01) is the determinant. DM is a strong predictor for death in univariate analysis (p = 0.00).

Conclusion PCI is a safe and effective method of coronary revascularization in elderly patients, and some risk factors can predict long-term MACE in this group of patients.

Keywords

elderly population

diabetes mellitus

major adverse cardiac events

percutaneous coronary intervention

Introduction

The world’s population is increasing at a rapid pace, and the aging population is also increasing; an increase in the life expectancy of the aging population has resulted in the increased prevalence of non-communicable diseases, particularly cardiovascular diseases and coronary artery disease (CAD). So there is an increased number of elderly people who present with chronic stable angina and acute coronary syndrome (ACS) who are referred for coronary revascularization, either by coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Elderly patients have significant comorbidities and risk factors, which preclude them, to undergo CABG. Relatively less invasive methods, like PCI, are preferred in the elderly, and gradually the number of elderly patients for revascularization procedures like PCI is on the rise. Elderly people have several comorbidities and are usually not in a healthy condition, and most of the risk factors are the cause for mortality and morbidity following coronary revascularization.

Nevertheless, elderly patients are less likely to undergo revascularization than younger patients, despite having more extensive CAD. Age alone is often the main reason why PCI is avoided. Moreover, elderly patients are often frail and have multiple comorbidities, which increase the risks associated with PCI. Over the last decades, advancement in PCI outcomes has led to an increasing number of elderly patients undergoing revascularization for symptomatic CAD.

Several studies have discussed the risk factors for mortality and outcome of CABG in the elderly,1 2 but the number of studies on the predictors for major adverse cardiac events (MACE) following PCI is limited. As of now, higher age; female gender; urgent or primary PCI; multivessel disease; hemodynamic instability; renal insufficiency; and some other clinical, angiographic, and procedural factors have been described as predictors for MACE in the elderly in some studies.3 4 5 6 However, the results of many of these studies are inconsistent, and this may be due to the differences in the clinical settings, and ethnic and genetic factors; more studies are required to reach an opinion for predicting factors that are responsible for MACE. Moreover, most studies have shown that in-hospital and short-term MACE, but not the long-term outcomes. In this present study, we studied the various predictors of long-term MACE in the elderly candidates for elective PCI at a tertiary care center for cardiovascular diseases.

Material and Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, we have studied the details of elderly patients (age ≥70 years) who underwent elective PCI at our center between 2008 and 2018. Inclusion criteria were age ≥70 years; single- and multivessel disease; normal, mild, moderate, and severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction; and complete follow- up data, unless the study endpoint occurred. Incomplete clinical and angiographic data, patients who had primary or early PCI within 24 hours after acute myocardial infarction, chronic kidney disease (CKD), cardiogenic shock, and patients whom we could not do follow-up even for 1 year were the main exclusion criteria. Demographic data, clinical history, angiographic data, and PCI procedure data of the selected patients were retrieved based on the study criteria from the angiography/PCI records of our center. Demographic data included age and sex, and anthropometric measurements of weight and height for calculating body mass index (BMI). The clinical history comprised cardiovascular risk factors, including diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking, and family history of CAD. Other details that were collected included previous CABG or PCI, presence of peripheral vascular disease or cerebrovascular accidents, ejection fraction based on echocardiography before the intervention, as well as the angiographic and angioplasty data. The PCI procedures were performed based on the standard techniques with either radial or femoral approach. Based on our routine, all patients received 300 to 600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel plus 325 mg of aspirin, rosuvastatin 40 mg before the procedure, and 70 to 100 IU/kg intravenous unfractionated heparin during PCI.

The clinical follow-up data were collected by scheduled clinic evaluations or direct telephone interviews at 15 days, 1 month, 6 months, and every yearly. All events were recorded from the time of intervention. MACE was defined as the occurrence of one or more of the following items within at least 5 years after PCI: (1) cardiac death, (2) myocardial infarction, (3) CABG, (4) re-hospitalization due to unstable angina, (5) target vessel revascularization (TVR) or target lesion revascularization (TLR), and (6) heart failure. Patients were characterized in the study group as those with or without MACE, and their data were then compared and analyzed using the statistical analysis in a univariable and binary linear regression analysis to identify the predictor determinants for MACE. Chi-square test and student’s t-test were used to know the significance between the continuous and discrete data. A p value of <0.05 is taken as significant level; descriptive statistics were done using SPSS software version 21 (Quarry Bay, Hong Kong).

Results

The patients were older than 70 years, and of all the 355 patients underwent elective PCI. There were more men than women in the elderly patients aged 70 years and theyhad comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, history of heart failure, previous CABG, and presentation with the acute coronary syndrome (Table 1). They are less likely to be current smokers and to present with ST segment elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI).

|

Variable |

Mean ± standard deviation |

|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CSA, chronic stable angina; DM, diabetes mellitus; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HTN, hypertension; K+, potassium; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; Na+, sodium; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RBS, random blood sugar; PCV, packed cell volume; SM, smoker; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein. |

|

|

Age (y) |

74.23 ± 4.21 |

|

• Male |

247 (69.5%) |

|

• HTN |

273 (76.9%) |

|

• DM |

232 (65.35%) |

|

• SM |

42 (11.83%) |

|

• CSA |

234 (65.9%) |

|

• LV dysfunction present |

104 (29.29%) |

|

• Previous PCI |

54 (15.21%) |

|

• CABG |

26 (7.32%) |

|

• Systolic BP (mm Hg) |

158.86 ± 32.05 |

|

• Diastolic BP (mm Hg) |

72.74 ± 14.15 |

|

• RBS |

143.58 ± 66.77 |

|

• Leucocyte count |

8,617 ± 2,699 |

|

• Hemoglobin (g[%]) |

12.25 ± 1.45 |

|

• PCV |

33.89 ± 5.62 |

|

• Platelet count |

2.23 ± 0.78 |

|

• Blood urea |

34.22 ± 16.91 |

|

• Serum creatinine |

1.15 ± 0.38 |

|

• GFR |

51.7 ±18.03 |

|

• Na+ |

137 ± 10.16 |

|

• K+ |

4.02 ± 0.81 |

|

• Total cholesterol |

149 ± 29.07 |

|

• LDL |

77.30 ± 28.47 |

|

• HDL |

39.04 ± 11.86 |

|

• VLDL |

32.38 ± 29.59 |

|

• Triglycerides |

112.63 ± 49.20 |

|

• Ratio (cholesterol/HDL) |

3.64 ± 1.22 |

|

• BMI |

24.9 ± 3.37 |

The differences in risk factors and laboratory parameters are listed in Table 2 and the demographic, clinical, and PCI follow-up between both sexes along with p values are noted in Table 3. Female elderly patients were more anemic (p = 0.000) with less GFR (p = 0.002).

|

Variable |

Male (n = 247) |

Female (n = 108) |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: CSA, chronic stable angina; DM, diabetes mellitus; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HTN, hypertension; K+, potassium; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; Na+, sodium; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RBS, random blood sugar; PCV, packed cell volume; SM, smoker; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein. |

|||

|

• HTN |

188 (76.1%) |

85 (78.7%) |

0.588 |

|

• DM |

163 (65.9%) |

69 (63.89%) |

0.703 |

|

• SM |

40 (16.2%) |

2 (1.8%) |

0.000 |

|

• CSA |

168 (68.01%) |

66 (61.11%) |

0.214 |

|

• SVD |

169 (68.4%) |

67 (62.03%) |

0.248 |

|

• Radial route |

168 (68.01%) |

73 (67.5%) |

0.937 |

|

• Leucocyte count |

8,545 ± 2,832 |

8,780 ± 2,379 |

0.518 |

|

• Hemoglobin |

12.59 ± 1.39 |

11.48 ± 1.32 |

0.000 |

|

• PCV |

33.89 ± 5.93 |

33.89 ± 5.93 |

0.986 |

|

• Platelet count |

2.260 ± 0.774 |

2.188 ± 0.817 |

0.542 |

|

• Urea |

33.7 ± 15.7 |

35.4 ± 19.4 |

0.454 |

|

• Creatinine |

1.169 ± 0.338 |

1.115 ± 0.465 |

0.324 |

|

• GFR |

54.4 ± 18.5 |

46.3 ± 15.9 |

0.002 |

|

• Na+ |

136.79 ± 7.50 |

137.5 ± 14.7 |

0.702 |

|

• K+ |

3.938 ± 0.779 |

4.208 ± 0.824 |

0.019 |

|

• RBS |

142.1 ± 65.7 |

147.7 ± 70.2 |

0.647 |

|

• Total cholesterol |

146.9 ± 23.7 |

152.9 ± 38.7 |

0.681 |

|

• HDL |

38.4 ± 11.7 |

40.2 ± 12.7 |

0.731 |

|

• LDL |

70.9 ± 23.1 |

90.0 ± 35.1 |

0.168 |

|

• VLDL |

29.9 ± 18.3 |

37.1 ± 45.0 |

0.655 |

|

• Triglycerides |

112.7 ± 52.7 |

112.4 ± 44.3 |

0.989 |

|

Variable |

Male |

Female |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CSA, chronic stable angina; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; LVD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SM, smoker; SVD, single-vessel disease. |

|||

|

No |

244 |

105 |

|

|

• Age (y) |

74.33 ± 4.17 |

74.11 ± 4.30 |

0.662 |

|

• BMI |

25.48 ± 3.05 |

23.58 ± 3.71 |

0.000 |

|

• HTN |

185 (75.8%) |

84 (80%) |

0.381 |

|

• DM |

160 (65.6%) |

66 (62.8%) |

0.628 |

|

• SM |

40 (16.4%) |

2 (1.9%) |

0.000 |

|

• Type of CAD (CSA) |

166 (68.03%) |

64 (60.9%) |

0.208 |

|

• LVD (yes) |

66 (27.05%) |

32 (30.48%) |

0.519 |

|

• Previous PCI |

41 (16.8%) |

13 (12.3%) |

0.270 |

|

• Previous CABG |

20 (8.2%) |

5 (0.47%) |

0.207 |

|

• SVD |

166 (68.03%) |

67 (63.8%) |

0.447 |

|

• Radial |

167 (68.4%) |

71 (67.6%) |

0.880 |

|

• In-hospital events • occurred |

9 (3.7%) |

2 (1.9%) |

0.321 |

|

• Follow-up events |

13 (5.2%) |

11 (10.2%) |

0.129 |

As mentioned in Table 3, the only prominent difference between both the genders was BMI other than smoking. Women had lesser BMI (p = 0.000); there were lesser smokers among women (p = 0.000).

In a total of 355 elderly patients, 24 events occurred in 1 year. The descriptions of the events are mentioned in Table 4. Mortality occurred in 6 (25%) patients.

|

Event description |

Number (%) |

|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CIN, contrast-induced nephropathy; CSA, chronic stable angina; Re-PCI, repeat percutaneous coronary intervention; SVD, single-vessel disease. |

|

|

Death |

6 (25%) |

|

• CSA |

1 (4.16%) |

|

• Heart failure |

10 (41.6%) |

|

• Subacute stent thrombosis |

2 (8.33%) |

|

• Statin-induced myopathy |

1 (4.16%) |

|

• Re-PCI |

2 (8.36%) |

|

• CABG |

1 (4.16%) |

Univariate analysis (Table 5) showed that DM (0.01) was the determinant for the occurrence of events. In addition, in the subgroup analysis of events, DM was a strong predictor for death (p = 0.00). This analysis did not show any other correlating parameters with the follow-up events.

|

Variable |

With follow-up events |

Without follow-up events |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CSA, chronic stable angina; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; LVD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SM, smoker; SVD, single-vessel disease. |

|||

|

No |

24 |

331 |

|

|

• Age (y) |

74.2 ± 5.6 |

74.2 ± 4.1 |

0.12 |

|

• BMI |

23.8 ± 3.4 |

24.98 ± 3.4 |

0.99 |

|

• Sex (male) |

13 (54.2%) |

234 (70.7%) |

0.12 |

|

• HTN |

18 (75%) |

255 (757.03) |

0.82 |

|

• DM |

20 (83.3%) |

212 (64.1%) |

0.02 |

|

• SM |

2 (8.3%) |

331 (12.1%) |

0.52 |

|

• Type of CAD (CSA) |

18 (75%) |

216 (65.3%) |

0.29 |

|

• LVD (YES) |

8 (33.3%) |

91 (27.9%) |

0.56 |

|

• Previous PCI |

2 (8.3%) |

52 (15.7%) |

0.22 |

|

• Previous CABG |

3 (12.5%) |

23 (6.9%) |

0.42 |

|

• SVD |

17 (70.8%) |

219 (66.2%) |

0.63 |

|

• Radial |

13 (54.2%) |

228 (68.9%) |

0.16 |

|

• In-hospital events occurred |

2 (8.3%) |

10 (3.02%) |

0.35 |

Binary logistic regression (Table 6) also showed that the only determinant for the 1-year follow-up adverse outcome was diabetes (p = 0.000).

|

Variables |

Chi-square |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CSA, chronic stable angina; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; LVD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SM, smoker; SVD, single-vessel disease. |

||

|

Age |

0.28 |

0.598 |

|

• BMI |

2.11 |

0.146 |

|

• Sex |

1.90 |

0.168 |

|

• HTN |

0.52 |

0.472 |

|

• DM |

6.68 |

0.01 |

|

• SM |

0.01 |

0.931 |

|

• CSA |

1.02 |

0.314 |

|

• LVD |

0.12 |

0.731 |

|

• Previous PCI |

0.99 |

0.32 |

|

• Previous CABG |

0.30 |

0.586 |

|

• SVD |

0.14 |

0.706 |

|

• Radial |

2.30 |

0.129 |

|

• In-hospital events |

1.94 |

0.164 |

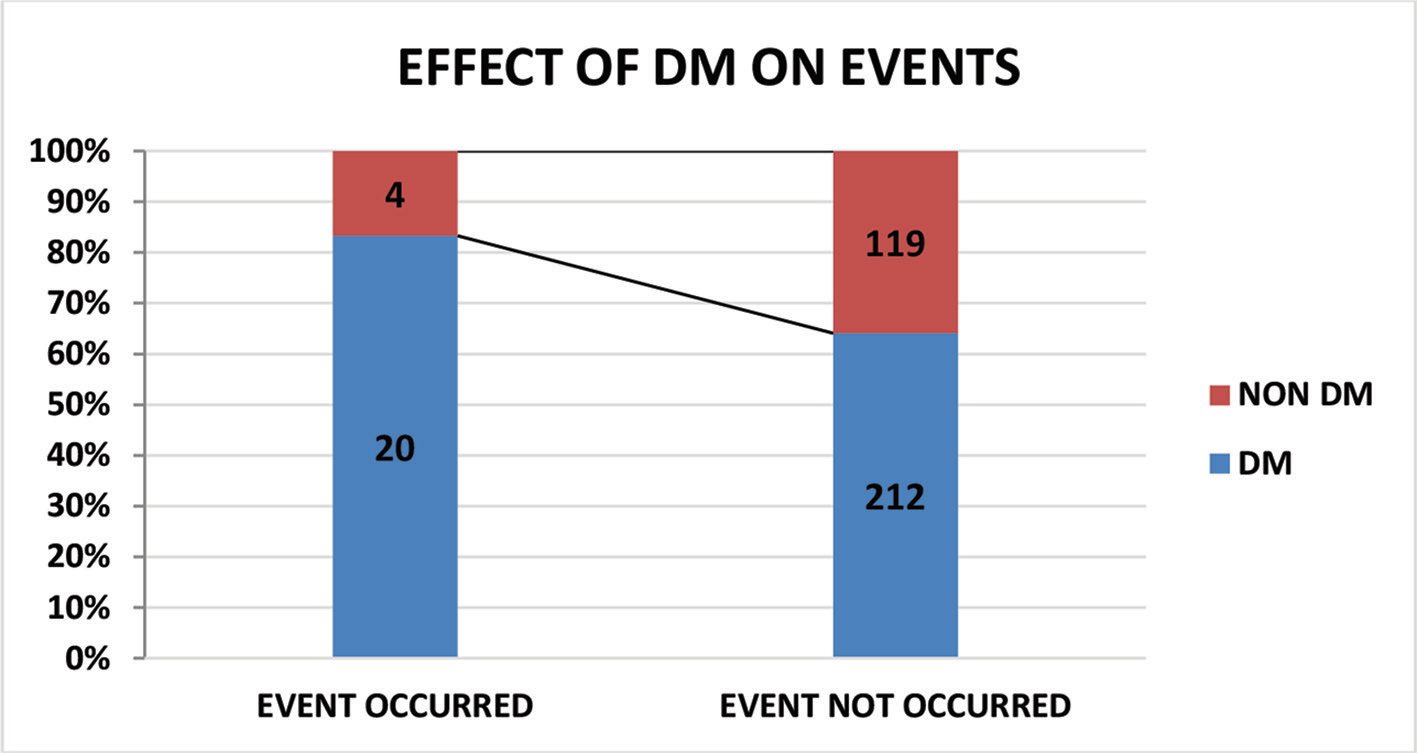

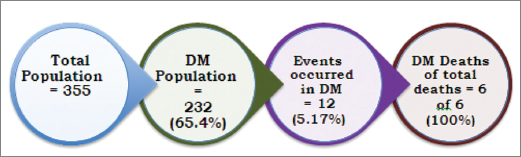

DM was more (83.3%) in patients who had MACE (20 out of 24), whereas DM was there in 64.1% in the group who did not have MACE (221 out of 331) (Fig. 1), which was statistically significant (p = 0.02). Fig. 2 is showing in events in the patients with DM.

-

Fig. 1 Effect of DM on events.

Fig. 1 Effect of DM on events.

-

Fig. 2 Events in DM patients.

Fig. 2 Events in DM patients.

Discussion

In the present study, we analyzed the risk factors which predict MACE in patients older than 70 years who underwent PCI in our center. We found that when compared between male and female sexes, presence of higher BMI and smoking were risk factors for MACE. However, as BMI is high in men because of high body surface area (BSA), when corrected to BSA the utility of BMI as a long-term predictor for MACE is not reliable. Similarly, smoking in Indian women patients is less and also under-reported, so it is less reliable as a predictor for MACE. The MACE in our population occurred in 24 patients, of whom 20 had DM; 212 patients had no events out of a total of 232 patients with DM. Clinical research in the elderly, who have significant comorbidities and whose population is increasing rapidly, is a crucial issue.7 Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death all over the world, and the number of patients undergoing elective PCI is increasing day by day for coronary revascularization.8 PCI is currently taken as a method for revascularization in the elderly.9 Therefore, studying the predictors for long-term MACE in the elderly patients who are subjected to elective PCI is an important issue as they have a higher rate of MACE as compared with the younger patients who underwent elective PCI.10 11

Several research studies have been done to evaluate the short-term predictors of adverse outcomes MACE in the elderly following the elective PCI, but then there is a paucity of research conducted for the long-term MACE outcomes in elderly people who underwent elective PCI. In one study, older age was a risk factor for MACE, and renal, neurological, and access-site complications were all more frequent in the very elderly (≥85 years) patients. Based on the data of a large PCI registry, hemodynamic instability and acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction were the strong predictors for in-hospital mortality and morbidity in patients with age ≥75 years who underwent primary PCI. Causative factors for death also include the periprocedural complications like contrast-induced nephropathy and stroke, which account for the powerful determinants in the elderly population who are undergoing elective PCI. Other studies which analyzed the influence of age on the procedural success and long-term outcomes following primary or elective PCI in elderly patients showed that decreased ejection fraction, not the age, was the most reliable predictor of mortality at 1 year; so, elective PCI in the elderly population is a better choice as the rate of MACE depends on the LV function.12

To study the long-term outcomes of PCI and their predictors in the elderly, a study conducted by Boudou et al with a follow-up of 51.3 months has shown that older age, LVEF <40%, high creatinine level, and prior carotid surgery or stroke were the independent predictors of long-term mortality.13 Gao et al studied that elderly women have the most significant risk factors for MACE in a 3-year follow-up study.14 In a study with a 5-year follow-up of 201 cases conducted by Chen et al, recognized incomplete revascularization is the only predictor of adverse outcomes following PCI in the elderly.15 Similarly, a study conducted by Hoebers et al showed that procedural success and diabetes mellitus were the independent predictors of MACE in the patients aged ≥75 years, which is similar to our study group.16 In our study, we have only selected patients with successful PCI; therefore, the effect of unsuccessful PCI on MACE could not be assessed, which is one of the limitations of our study. A study conducted in Mexico by Miranda et al showed that heart failure, cardiogenic shock, DM, TIMI flow 0 to 2 before and after intervention, and A-V block or atrial fibrillation as the long-term predictors of MACE.17 Hypertension was the only predictor of all-cause mortality in patients aged ≥75 years in another study conducted by Schroder.18 A study conducted by Sinning et al showed that combined model of angiographic and clinical characteristics, patients with high Euro score and high SYNTAX (The Synergy between PCI with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery) score were at higher risk for developing MACE within 3 years of follow-up.19 The study conducted by Uthamalingam et al showed that the use of bare metal stent (BMS) had increased the risk of MACE compared with those patients who are treated with DES.20

In our study, six deaths are reported; out of them three had single-vessel disease (SVD) and the other three had multivessel disease (MVD), and all six patients had DM. DM is the single strongest predictor of mortality in our group.

Similar to our findings, diabetes mellitus is shown as an independent risk factor for mortality in the elderly with chronic total occlusion treated by PCI.16 17 21 22 This suggests the devastating effects of diabetes mellitus on the body, in particular to cardiovascular systems.

Future Perspective

Future research should be focused on the effects of DM on the body, type of antiglycemic treatment, or the levels of glycosylated hemoglobin or fasting blood sugar and duration of DM on the occurrence of MACE in the elderly candidates who undergo elective or primary PCI.

Large population, long-term follow-up period, and the effect of various risk factors that predict MACE in the elderly population are the strengths of our study.

Limitations

This study had the following limitations.

This is a single-center study, performed at a tertiary care hospital.

The effect of unsuccessful PCI on MACE could not be assessed.

Cases were spread over a decade; so, PCI gadgetry improvements that also influence the PCI outcomes were not included in the analysis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, PCI is safe and is an effective method of coronary revascularization in elderly patients. We found that diabetes mellitus was an independent predictor of MACE in the elderly. Gender, single- or multivessel involvement, and left ventricular systolic dysfunction have an influence on MACE in elderly. Univariate analysis showed that BMI and smoking were also the risk factors seen in the men in our study, but not in multivariate analysis.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Comparison of the safety and efficacy of on-pump (ONCAB) versus off-pump (OPCAB) coronary artery bypass graft surgery in the elderly: a review of the ANZSCTS database. Heart Lung Circ. 2015;24(12):1225-1232.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mortality in isolated coronary artery bypass surgery in elderly patients. A retrospective analysis over 14 years. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2017;64(05):262-272.

- [Google Scholar]

- In-hospital outcomes of very elderly patients (85 years and older) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;77(05):634-641.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of hospital mortality in the elderly undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndromes and stable angina. Int J Cardiol. 2011;151(02):164-169.

- [Google Scholar]

- Survival outcomes post percutaneous coronary intervention: Why the hype about stent type? Lessons from a healthcare system in India. PLoS One. 2018;13(05):e0196830.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lotfi-Tokaldany M, Hakki E, Sheykh Fathollahi M. Using workload to predict left main coronary artery stenosis in candidates for coronary angiography. J Tehran Heart Cent. 2007;2(03):145-150.

- [Google Scholar]

- The necessity for research on the elderly in Iran. J Tehran Heart Cent. 2012;7(01):40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global burden of cardiovascular disease.Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2005. In: eds.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous coronary intervention in elderly patients: is it beneficial? Tex Heart Inst J. 2011;38(04):398-403.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous coronary intervention in the elderly: changes in case-mix and periprocedural outcomes in 31,758 patients treated between 2000 and 2007. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3(04):341-345.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term clinical outcome of elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome treated with early percutaneous coronary intervention: Insights from the BASE ACS randomized controlled trial: bioactive versus everolimus-eluting stents in elderly patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;37:43-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous coronary intervention in very elderly patients. In-hospital mortality and clinical outcome. Heart Lung Circ. 2011;20(10):622-628.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous coronary intervention in the elderly: procedural success and 1-year outcomes. Am J Geriatr Cardiol. 2003;12(06):366-368.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term clinical outcome after percutaneous coronary interventions in the elderly: results for 512 consecutive patients. EuroIntervention. 2008;3(04):512-517.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is being an elderly woman a risk factor for worse outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention? A large cohort study from one center. Angiology. 2014;65(07):596-601.

- [Google Scholar]

- Safety and effectiveness of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in elderly patients. A 5-year consecutive study of 201 cases with PCI. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;51(03):312-316.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term clinical outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention for chronic total occlusions in elderly patients (75 years): five-year outcomes from a 1,791 patient multi-national registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;82(01):85-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of mortality and adverse outcome in elderly high-risk patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Arch Cardiol Mex. 2007;77(03):194-199.

- [Google Scholar]

- Are the elderly different? Factors influencing mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention with stent implantation. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;46(02):144-150.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combination of angiographic and clinical characteristics for the prediction of clinical outcomes in elderly patients undergoing multivessel PCI. Clin Res Cardiol. 2013;102(12):865-873.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long term outcomes in octogenarians undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: comparison of bare metal versus drug eluting stent. Int J Cardiol. 2015;179:385-389.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of diabetes on long term follow-up of elderly patients with chronic total occlusion post percutaneous coronary intervention. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2013;10(01):16-20.

- [Google Scholar]