Translate this page into:

Structural and Functional Changes in Maternal Heart during Pregnancy: An Echocardiographic Study

Sumalatha Beeram, MS Department of OBG Gandhi Medical College, Hyderabad, TS 500003 India sumalatha_08@Yahoo.co.in

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Background Pregnancy is associated with profound physiologic alterations in the maternal cardiovascular system. This study aimed to investigate maternal cardiac performance during normal pregnancy by two-dimensional echocardiography parameters and various functional and structural alterations.

Methods This was a cross-sectional study of 100 normal pregnant women who attended the antenatal clinic, and all participants had clinical history, physical examination, and 12-lead electrocardiogram. Two-dimensional, M-mode, and Doppler echocardiography was done. Echocardiographic parameters were compared with normal age-matched controls from previously published studies.

Results The mean age of the study group was 23.35 ± 3.05 years, mean systolic blood pressure was 110.5 ± 8.69 mm Hg, and mean diastolic blood pressure was 71.6 ± 6.77 mm Hg. There was an increase in left atrial (LA) diameter, left ventricular end diastolic diameter, and interventricular septum (IVS) thickness as gestational age advanced. There was a gradual decrease in E-wave velocity, and E/A ratio increased during the second trimester and decreased during the third trimester. The E-wave deceleration time increased with gestational age There was no statistically significant difference between IVS thickness and E/A ratio (p = 1.000).

Conclusion Cardiac chamber dimensions, LV wall thickness, and LA size, most indices of systolic function although within normal range, were significantly higher in pregnant Asian Indian women than in the controls. This study shows that the subtle reduction in myocardial compliance appears as an adaptive response to changes of preload, afterload, and LV geometry.

Keywords

pregnancy

two-dimensional echocardiography

cardiovascular system

Introduction

Pregnancy is a physiologic state associated with a dramatic cardiac structural remodeling and an improved functional performance.1 Cardiac adjustments to a pregnancy state may mimic abnormalities of the cardiovascular system.2 3 4 Physiologic changes occur in pregnancy to nurture the developing fetus and prepare the mother for labor and delivery. Some of these changes influence normal biochemical values whereas others may mimic symptoms of heart disease. Plasma volume increases progressively throughout normal pregnancy. Most of this 50% increase occurs by 34 weeks’ gestation and is proportional to the birth weight of the baby, which adds hemodynamic load to the circulatory system that produces physiologic alterations resulting from structural and functional alterations in the cardiac muscle.

Echocardiography can assess the hemodynamic changes noninvasively; thus, it is widely used to measure cardiocirculatory indices during pregnancy and after delivery.5 Regarding the changes in echocardiographic parameters, left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic and end-systolic dimensions and wall thickness increase, and contractile function enhances. Functional pulmonary, tricuspid, and mitral regurgitation and mild pericardial effusion are occasionally seen in normal pregnancy. However, there was nonuniformity in the published literature with various echocardiographic parameters and their alterations with each trimester. As there were differences in echocardiographic findings in pregnant women of differing ethnicity, the authors wanted to study two-dimensional (2D) echocardiographic features in Asian pregnant women.

Methods

These were cross-sectional data of pregnant women across all stages of gestation who attended antenatal clinic at the institute on Women's Day. The study was conducted after obtaining approval by the institutional ethics committee. Informed consent was taken from each participant after explaining the procedure. Their medical and obstetric history was taken in detail and further clinical examination was done.

Inclusion criteria included normal healthy pregnant women with singleton pregnancy. Exclusion criteria included women with any organic cardiac disease, renal disease, thyroid disease, severe anemia, diabetes, hypertension, and on any chronic medication.

Each participant was interviewed with a structured questionnaire. All participants had clinical history, physical examination, and 12-lead electrocardiogram. Two-dimensional, M-mode, and Doppler echocardiography was done. Transthoracic echocardiography was performed using the 4s probe for adults with Philips ultrasound machine. Measurements were based on the recommendations of American Society of Echocardiography.6 7 8 9 Left atrial (LA) size, LV systolic and diastolic dimensions, LV systolic function by ejection fraction (EF), and LV diastolic function were assessed by 2D echocardiography. Diastolic function was assessed by determining early (E) and late (A) transmitral filling velocities as well as E/A ratio, deceleration time of the transmitral E wave, and the iso-volumetric relaxation time.

The data were analyzed using the Minitab version 17 (Minitab, Ltd.) Categorical variables were expressed as proportions (counts) and percentages, whereas continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). In all the statistical tests, a value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The study group consisted of 100 pregnant women, out of whom 7 women were in the first trimester, 28 in the second trimester, and 65 in the third trimester, as listed in Table 1. The mean age of the study group was 23.35 ± 3.05 years, mean systolic blood pressure was 110.5 ± 8.69 mm Hg, and mean diastolic blood pressure was 71.6 ± 6.77 mm Hg. Thirty-nine percent (n = 39) women were nulliparous and 61% (n = 61) were multiparous.

|

S. No. |

Group |

First trimester |

Second trimester |

Third trimester |

Total no. of patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Primigravidae |

4 |

11 |

24 |

39 (39%) |

|

2 |

Multigravidae |

3 |

17 |

41 |

61 (61%) |

|

Total no. of patients |

7 (7%) |

28 (28%) |

65 (65%) |

100 |

Cardiac chamber dimensions, LV systolic function, and LV wall thickness in normal pregnant and healthy nonpregnant women were compared. Data of the nonpregnant women were taken from previously published studies. Normal values were taken from previously published studies references (Tables 2, 3).10 11 12

|

Cardiac chamber dimensions |

FT |

ST |

TT |

Normal values |

ANOVA in between the trimesters |

p Value (comparison between all trimesters and normal, FT and normal, ST and normal, TT and normal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; EF, ejection fraction; FT, first trimester; IVS, interventricular septum; LA, left atrial; LV, left ventricular; PWT, posterior wall thickness; ST, second trimester; TT, third trimester. |

||||||

|

LA (cm) |

2.57 ± 0.09 |

2.81 ± 0.41 |

2.73 ± 0.27 |

2.7–3.8 |

F = 1.87, p = 0.16 |

p = 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

|

LV diastolic diameter (cm) |

4.08 ± 0.49 |

4.18 ± 0.43 |

4.02 ± 0.53 |

3.9–5.3 |

F = 1.02, p = 0.36 |

p = 0.00, 0.021, 0.001, 0.00 |

|

LV systolic diameter (cm) |

2.67 ± 0.22 |

2.6 ± 0.56 |

2.73 ± 0.34 |

3.1–3.3 |

F = 0.95, p = 0.89 |

p = 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

|

EF (%) |

71 ± 9.85 |

68.18 ± 6.5 |

69.14 ± 8.15 |

58 ± 3 |

F = 0.39, p = 0.68 |

p = 0.00, 0.012, 0. 00, 0.00 |

|

PWT (cm) |

0.88 ± 0.11 |

0.87 ± 0.11 |

0.90 ± 0.09 |

0.6–0.9 |

F = 0.94, p = 0.4 |

p = 0.00, 0.024, 0.01, 0.00 |

|

IVS (cm) |

0.85 ± 0.12 |

0.89 ± 0.12 |

0.93 ± 0.15 |

0.6–0.9 |

F = 1.12, p = 0.33 |

p = 0.01, 0.26, 0.01, 0.00 |

|

Doppler parameters |

First trimester |

Second trimester |

Third trimester |

Normal values |

ANOVA in between the trimesters |

p Value (comparison between all trimesters and normal, FT and normal, ST and normal, TT and normal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; DT, deceleration time; EDT, E-wave deceleration time; FT, first trimester; IVS, interventricular septum; ST, second trimester; TT, third trimester. |

||||||

|

E wave (m/s) |

0.84 ± 0.7 |

0.83 ± 0.15 |

0.79 ± 0.12 |

1.06 ± 1.1 |

F = 1.44, p = 0.24 |

p = 0.09, 0.12, 0.11, 0.06 |

|

A wave (m/s) |

0.60 ± 0.46 |

0.587 ± 0.13 |

0.59 ± 0.12 |

0.71 ± 0.95 |

F = 0.18, p = 0.88 |

p = 0.002, 0.007, 0.005, 0.07 |

|

E/A ratio |

1.41 ± 0.14 |

1.48 ± 0.32 |

1.37 ± 0.22 |

1.88 ± 0.45 |

F = 2.11, p = 0.12 |

p = 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

|

EDT |

117.14 ± 16.93 |

135.79 ± 40.46 |

125.68 ± 26.39 |

142 ± 19 |

F = 1.34, p = 0.22 |

p = 0.04, 0.016, 0.76, 0.03 |

There were increase in LA size and LV E-wave deceleration time (EDT) from the first to second trimester and slight decrease during the third trimester even though there was no statistically significant difference between trimesters and normal range. LV end-systolic diameter (ESD), LV posterior wall thickness (PWT), and IVS thickness gradually increased as the increasing trimesters. LVEF showed a declining trend with increasing trimester. However, all the values were in the normal range.

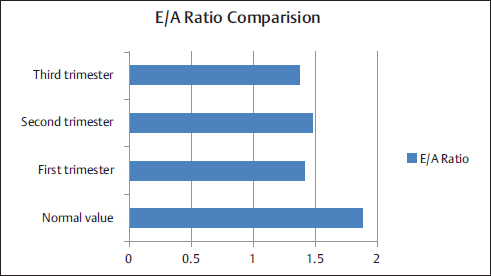

There was a gradual decrease in E-wave velocity and no significant change in A-wave velocity with increasing gestational age. The E/A ratio increased during the second trimester and decreased during the third trimester (Fig. 1). The EDT increased with gestational age reaching maximum in the second trimester and decreased during the third trimester (Fig. 2). There was no statistically significant difference noted between IVS thickness and E/A ratio, DT and E/A ratio, and DT and IVS thickness (Tables 4–6).

-

Fig. 1 E/A ratio comparison in normal pregnant women and healthy nonpregnant women.

Fig. 1 E/A ratio comparison in normal pregnant women and healthy nonpregnant women.

-

Fig. 2 Two-dimensional echo diastolic parameters.

Fig. 2 Two-dimensional echo diastolic parameters.

|

IVS < 0.75 |

IVS ≥ 0 0.75 |

Total |

p Value 1.000 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E/A ratio < 1.5 |

5 |

74 |

79 |

|

|

E/A ratio ≥ 1.5 |

4 |

17 |

21 |

|

|

Total |

9 |

91 |

100 |

|

DT < 123 |

IVS ≥ 123 |

Total |

p Value 0.000 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E/A ratio < 1.5 |

4 |

4 |

8 |

|

|

E/A ratio ≥ 1.5 |

19 |

73 |

92 |

|

|

Total |

23 |

77 |

100 |

|

DT < 123 |

DT ≥ 123 |

Total |

p Value 0.000 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

There was no statistically significant difference between IVS thickness and E/A ratio, DT and E/A ratio, and DT and IVS thickness. |

||||

|

IVS < 0.75 |

5 |

4 |

9 |

|

|

IVS ≥ 0.75 |

18 |

73 |

91 |

|

|

Total |

23 |

77 |

100 |

|

Discussion

It was well known that the maternal cardiovascular system undergoes significant changes throughout pregnancy, which imposes considerable stress on the pregnant woman's heart. In this study, the authors demonstrated structural and functional changes in the maternal cardiovascular system during pregnancy. During early pregnancy, LV filling rates increase because of increased venous return to the left atrium (preload), represented by an increase in LA size and LV internal diameters from the first to second trimester. As gestation advances, the myocardium develops physiologic hypertrophy to withstand the chronic volume overload on cardiovascular system. In this study, there was a gradual increase in IVS and LV PWT as increasing gestational age. There was a progressive increase in these parameters across trimesters in other studies.2 13 14 Mesa et al1 showed an increase in the LV end-diastolic volume as early as 10 weeks’ gestation and a peak during the third trimester by echocardiography, whereas Geva et al15 did not observe any change in LV end-diastolic or end-systolic dimension throughout pregnancy. Other reports showed that left and right atrial and right ventricular diastolic dimensions increased throughout the gestational period.14 16 LV end-diastolic septal and posterior wall thicknesses are increased similar to other studies.13 14 18 This may be due to preload alterations.18 Previous studies observed variable results with LVEF. In this study, there was no significant change in EF as gestation increases. Adeyeye et al13 reported a gradual increase in LVEF with increasing gestational age. More recent studies showed no significant change in LVEF during pregnancy,1 15 contrary to earlier report by Hunter and Robson3 who found an increase in LVEF during the first two trimesters. A progressive decrease in LV fractional shortening (LVFS) was found by Schannwell et al,14 whereas Mesa et al1 and Clapp and Capeless17 did not observe any change in LVFS during normal pregnancy. Cardiac diastolic function has been less studied than systolic function during pregnancy. The ratio of early-to-late diastolic flow velocity (E/A ratio) has been documented to be lower during the third trimester than at early trimesters and postpartum.14 16 19 In this study, the authors observed that there was a decrease in E-wave velocity, without decrease in A-wave velocity leading reduced E/A ratio during the third trimester. The E/A ratio was decreased significantly in the patients similar to other studies.13 14 16 19 However, there was no significant correlation between E/A ratio and IVS thickness as gestational age increases. As gestational age increases, the LV compliance decreases because of realignment of collagen fibers of the myocardium. As a result, the early diastolic filling rate decreases, which was reflected by the decrease in E-wave velocity. At the same time, the left atrium plays a predominant role in filling; therefore, the A-wave velocity increases with gestation and reaches a maximum level in the third trimester. These results are in agreement with those of other studies on transmitral inflow velocity during pregnancy in most, but not all, parameters. Mesa et al demonstrated that E-wave and E/A ratio decreased with advancing gestation, whereas the A wave increased throughout pregnancy, maximally in the third trimester. In conclusion, during pregnancy, LV compliance was reduced with augmented late-diastolic function to accommodate the increase in preload. Cardiac chamber dimensions, LV wall thickness, and LA size, most indices of LV systolic and diastolic functions although within normal range, were significantly higher in pregnant Asian Indian women than in the controls.

References

- Left ventricular diastolic function in normal human pregnancy. Circulation. 1999;99(04):511-517.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal cardiovascular hemodynamic adaptation to pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1994;49(12):S1-S14. Suppl)

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy and heart disease. Related live CME: 9th Annual Intensive Review of Cardiology; August 17–21, 2007

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of echocardiography in assessing pregnant women with and without heart disease. J Echocardiogr. 2008;6:29-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations regarding quantitation in M-mode echocardiography: results of a survey of echocardiographic measurements. Circulation. 1978;58(06):1072-1083.

- [Google Scholar]

- Doppler Quantification Task Force of the Nomenclature and Standards Committee of the American Society of Echocardiography. Recommendations for quantification of Doppler echocardiography: a report from the Doppler Quantification Task Force of the Nomenclature and Standards Committee of the American Society of EchocardiographyJ Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15(02):167-184.

- [Google Scholar]

- Doppler tissue imaging for the assessment of left ventricular diastolic function: a systematic approach for the sonographer. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(01):80-88. quiz 89

- [Google Scholar]

- Problems in echocardiographic—angiographic correlation in the presence or absence of asynergy. Am J Cardiol. 1976;37:7-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Normal echocardiographic parameters of healthy adult individuals working in National Heart Centre. Nepalese Heart J. 2012;9(01):3-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Normal values of echocardiographic measurements. A population-based studyArq Bras Cardiol. 2000;75(02):107-114.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22(02):107-133.

- [Google Scholar]

- Echocardiographic assessment of cardiac changes during normal pregnancy among Nigerians. Clin Med Insights Cardiol. 2016;10:157-162.

- [Google Scholar]

- [Left ventricular diastolic function in normal pregnancy. A prospective study using M-mode echocardiography and Doppler echocardiography] [in German]Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2000;125(37):1069-1073.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of physiologic load of pregnancy on left ventricular contractility and remodeling. Am Heart J. 1997;133(01):53-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal cardiac systolic and diastolic function: relationship with uteroplacental resistances. A Doppler and echocardiographic longitudinal studyUltrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;15(06):487-497.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular function before, during, and after the first and subsequent pregnancies. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80(11):1469-1473.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac structure and function in normal pregnancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;24(06):413-421.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal left ventricular mass and diastolic function during pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;18(05):460-466.

- [Google Scholar]