Translate this page into:

Sex-Based Difference in Clinical Presentation and Outcomes—A Single-Center Experience

Harini Anandan, BS Physician Assistant- cathlab, Madras Medical Mission 4-A JJ Nagar, Mogappair, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India- 600037 harinisundar2255@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Background and Aim The aim of this study was to compare the gender-based differences in baseline characteristics, clinical presentation, and outcomes among patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in our institute.

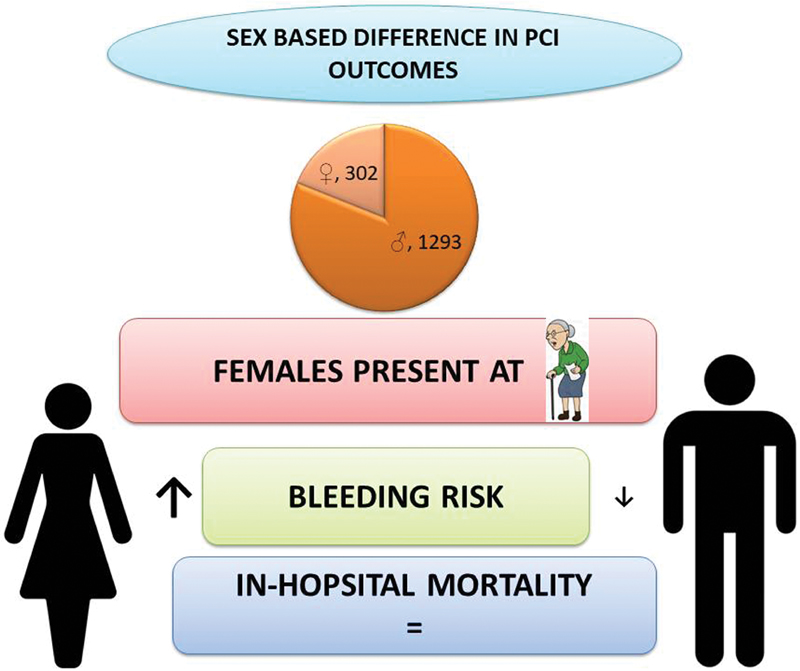

Methods This is a single-center, retrospective observational study. A total of 1,595 patients underwent PCI from a period of January 2019 to December 2019, in which 1,293 were males and 302 were females. Demographic characteristics, clinical and procedural details, and their in-hospital outcomes were all collected and analyzed.

Results Females presenting with symptoms were older than males (58 vs. 60.8 years, p < 0.001) and had higher body mass index (26.2 ± 6.7 vs. 27.2 ± 4, p < 0.001). Risk factors like diabetes mellitus (57.8 vs. 69.5%, p < 0.001) and systemic hypertension (50.2 vs. 65%, p < 0.001) were more common in females. Women were more likely to present with unstable angina (16.2 vs. 22.7%, p-0.009) and the rate of thrombolysis is low in women who presented with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (13.5 vs. 6.3%, p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in in-hospital mortality between both groups, but bleeding complications were higher in females (1.3 vs. 4%, p-0.006).

Conclusion Women who underwent PCI tend to be older and had higher rates of diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. Although mortality rates did not differ between groups, bleeding risk is higher in women.

Keywords

ST-elevation myocardial infarction

diabetes mellitus

cardiovascular disease

- Abstract Image

Abstract Image

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) was considered to be a disease of men, but it is the leading cause of mortality in women globally.1 CVD remains less diagnosed and poorly treated among women2 possibly due to differences in clinical presentation. Endogenous estrogen has wide-ranging effects throughout the circulatory system in women. It increases high-density lipoprotein and decreases the low-density lipoprotein.3 There is a loss of estrogen effect after menopause and also it is stated that heart disease develops 7 to 10 years later in women than in men.3 4 Women's Heart Alliance in 2017 showed that 45% of women are unaware of CVD is the leading cause of death,5 which shows that awareness is much needed among women. Generally, the presentations of women with ACS differ compared with men as 37% of women with ACS reported no chest pain. Commonly reported symptoms are back, neck, or jaw pain.6 An unrecognized symptom leads to delay in treatment with a longer time from symptom onset to balloon, thrombolysis, or timely interventions. GUSTO IIb trial (Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes) showed that women with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) were older than men and have a high incidence of risk factors like diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HTN), and dyslipidemia.7 The pathophysiology of ACS also differs among men and women. Plaque erosion due to endothelial dysfunction, toll-like receptor signaling, leukocyte activation, and modification of subendothelial matrix by endothelial or smooth muscle cells, trigger loss of adhesion to the extracellular matrix or endothelial apoptosis is the strong risk factors for ACS in women.8 The in-hospital mortality and morbidity are particularly higher in younger women than in man.9 10 The purpose of this study is to report a single-center experience in gender-based differences among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and related outcomes.

Methods

This is a single-center, retrospective observational study. Consecutive patients who underwent PCI between January 2019 to December 2019 were enrolled in the study. A total of 1,595 patients underwent PCI in which 1,293 were males and 302 were females. Demographic characteristics, clinical and procedural details, and their in-hospital events were all collected. The primary outcome of the study is to assess the demographic, clinical, and angiographic characteristics of male and female groups who underwent PCI. The secondary objective is to analyze their clinical outcomes and major cardio and cerebrovascular events (MACE). The clinical events reported in this study include all-cause mortality, reinfarction, and hemorrhagic stroke, major bleeding, minor bleeding, target lesion failure, and repeat revascularizations. The MACE rate has been reported as a composite of death, reinfarction, and stroke. The definitions of the above-mentioned outcomes were provided in Appendix A and Appendix B.11 12 13

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were summarized using descriptive statistics and the categorical data are presented as numbers with percentages. Comparison of categorical variables between the two groups has been done with a chi-squared test. Comparison between two means was tested using two-tailed, unpaired t-tests for normal distribution and Mann–Whitney U test for non-normal distribution and is set at the statistical significance of 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0

Results

Overall, 1,595 patients were enrolled in the study in which 81.1% were males and 19% were females.

Table 1 shows the baseline clinical characteristics. Females presenting with symptoms were older than males (58 vs. 60.8 years, p < 0.001) and had higher body mass index (BMI) (26.2 ± 6.7 vs. 27.2 ± 4, p < 0.001). Risk factors like DM (57.8 vs. 69.5%, p < 0.001) and systemic HTN (50.2 vs. 65%, p < 0.001) were common in female. Smoking and alcohol consumption were reported high among males. Chronic kidney disease was more common in males (3.6 vs. 0.7%, p = 0.005). The clinical presentations were reported in Table 2. Females were more likely to present as unstable angina (16.2 vs. 22.7%, p-0.009) and they are less likely to get thrombolysed when presented with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) (13.5 vs. 6.3%, p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in STEMI and non-STEMI group. The laboratory findings of blood parameters were shown in Table 3. Females had low hemoglobin (13.7 ± 2 vs. 11.7 ± 1.5, p < 0.001) and poor glycemic control (7.45 ± 1.9 vs. 8.06 ± 2.2, p < 0.001). The left ventricular function was given in Table 4.

|

Total no of patients: 1,595 |

Male: 1,293 |

Female: 302 |

p-Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age, mean (SD), years |

58.2 ± 10.8 |

58 ± 10.9 |

60.8 ± 9.1 |

<0.001 |

|

Height, mean (SD) |

162.6 ± 8.3 |

164.6 ± 7.5 |

154 ± 7.3 |

<0.001 |

|

BMI, mean (SD) |

26.3 ± 6.2 |

26.2 ± 6.7 |

27.2 ± 4 |

<0.001 |

|

Diabetes mellitus (%) |

957 (60) |

747(57.8) |

210 (69.5) |

<0.001 |

|

Hypertension (%) |

845 (53) |

649(50.2) |

196 (65) |

<0.001 |

|

Dyslipidemia (%) |

273 (17) |

215 (16.7) |

58 (19.3) |

0.3 |

|

Smoker (%) |

99 (6.2) |

99(7.7) |

0 |

<0.001 |

|

Alcoholic (%) |

91 (5.7) |

90 (7) |

1 (0.3) |

<0.001 |

|

Family history of CAD (%) |

240 (15) |

204 (15.8) |

36 (12) |

0.1 |

|

CVA (%) |

34 (2.1) |

29 (2.2) |

5 (1.7) |

0.6 |

|

COPD (%) |

5 (0.3) |

5 (0.4) |

0 |

0.6 |

|

CKD (%) |

49 (3.1) |

47 (3.6) |

2 (0.7) |

0.005 |

|

K/C/O CAD (%) |

471 (29.5) |

390 (30.2) |

81(27) |

0.3 |

|

H/O PCI (%) |

232 (14.5) |

190 (14.7) |

42 (14) |

0.9 |

|

H/O CABG (%) |

94 (5.9) |

82 (6.3) |

12 (4) |

0.1 |

|

Clinical presentation |

||||

|

Unstable angina (%) |

277 (17.4) |

209 (16.2) |

68 (22.7) |

0.009 |

|

MI < 90 days (%) |

513 (32.2) |

434 (33.6) |

79 (26.3) |

0.02 |

|

Thrombolysis (%) |

196 (12.1) |

174 (13.5%) |

19 (6.3%) |

< 0.001 |

|

NSTEMI (%) |

298 (18.7) |

236 (18.3%) |

62 (20.5%) |

0.4 |

|

STEMI (%) |

381 (23.8) |

310 (24%) |

71 (23.5%) |

0.9 |

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; MI, myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction.

|

Total no of patients: 1, 595 |

Male: 1,293 |

Female: 302 |

p-Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hemoglobin, mean (SD), g/dL |

13.3 (2.1) |

13.7 (2) |

11.7 (1.52) |

<0.001 |

|

Urea, mean (SD), mg/dL |

26.2 (11.9) |

26.4 (11.6) |

25.1(9.8) |

0.4 |

|

Creatinine, mean (SD), mg/dL |

0.9 (0.5) |

0.9 (0.6) |

0.7 (0.3) |

0.9 |

|

HbA1c, mean (SD), mg/dL |

7.5 (2) |

7.45 (1.9) |

8.06 (2.24) |

<0.001 |

Abbreviation: HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; SD, standard deviation.

|

Total no of patients: 1,595 |

Male: 1,293 |

Female: 302 |

p-Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

LVEF ≤45 (%) |

949 (59.5) |

782 (60.5%) |

167 (55.6%) |

0.1 |

|

LVEF > 45 (%) |

646 (40.5) |

511 (39.5%) |

135 (45%) |

Abbreviation: LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

|

Total no of patients: 1,595 |

Male: 1,293 |

Female: 302 |

p-Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Systolic BP mm Hg, mean (SD) |

140.6 (24.6) |

139.7 (24.5) |

146.5(25.7) |

<0.001 |

|

Diastolic BP mm Hg, mean (SD) |

78.4 (13.5) |

79.1 (13.9) |

75.6 (11.9) |

0.001 |

|

TPI (%) |

32 (2) |

23 (1.8%) |

9 (3%) |

0.2 |

|

IABP (%) |

83 (5.2) |

75 (5.8%) |

8 (2.6%) |

0.03 |

|

GpIIb/IIIa (%) |

198 (12.4) |

160 (12.4%) |

38 (12.6%) |

0.9 |

|

Heparin (%) |

1336 (83.7) |

1072 (83%) |

264 (87.7%) |

0.04 |

|

Bivalirudin (%) |

255 (116) |

220 (17%) |

35 (11.6%) |

0.02 |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; IABP, intraaortic balloon pump; TPI, temporary pacemaker implantation.

Sex Difference in Procedural Characteristics

The procedural and angiographic characteristics were reported in Tables 5 and 6. Intraaortic balloon pump usage was more in men (5.8 vs. 2.6%, p-0.03). There was no significant difference in vessels involved or the total number of lesions. Femoral access (53.6 vs. 65.3%, p < 0.001) was most preferred access for females as radial access (44.8 vs. 33.4%, p < 0.001) in men.

|

Disease |

Total no of patients: 1,595 |

Male: 1,293 |

Female: 302 |

p -Value |

|

SVD (%) |

1225 (76.8) |

999 (77.2) |

226 (74.8) |

0.4 |

|

DVD (%) |

334 (21) |

265 (20.5) |

69 (22.8) |

0.4 |

|

TVD (%) |

36 (2.3) |

29 (2.2) |

7 (2.3) |

1 |

|

Vessel involved |

Total no of lesions: 1,983 |

Male: 1,616 |

Female: 367 |

p -Value |

|

LAD (%) |

957 (48.2) |

767 (47.4) |

190(51.7) |

0.1 |

|

LCX (%) |

385 (19.4) |

322 (20) |

63(17.1) |

0.1 |

|

RCA (%) |

549 (27.7) |

455 (28.1) |

94(25.6) |

0.2 |

|

LM (%) |

28 (1.4) |

19 (1.2) |

9 (2.5) |

0.09 |

|

ISR (%) |

32 (1.6) |

23 (1.4) |

9(2.5) |

0.3 |

|

SVG (%) |

32 (1.6) |

30 (1.9) |

2(0.5) |

0.07 |

|

Access |

Total no of patients: 1,595 |

Male: 1,293 |

Female: 302 |

p -Value |

|

Brachial artery (%) |

1 (0.06) |

1 (0.1%) |

0 |

<0.001 |

|

Dorsoradial (%) |

12 (0.8) |

12 (0.9%) |

0 |

|

|

Femoral artery (%) |

889 (55.7) |

693 (53.6%) |

196 (65.3%) |

|

|

Radial artery (%) |

680 (43) |

579 (44.8%) |

101 (33.4%) |

|

|

Radial and femoral (%) |

13 (0.8) |

8 (0.6%) |

5 (1.7%) |

Abbreviations: DVD, double vessel disease; ISR, in-stent restenosis; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; LM, left main; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery; SVD, single-vessel disease; SVG, saphenous vein graft; TVD, triple-vessel disease.

|

Total no of patients: 1,595 |

Male: 1,293 |

Female: 302 |

p-Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hospital stay, mean (SD), days |

4 (2.2) |

3.9 (2.2) |

4 (2.3) |

0.2 |

|

Mortality (%) |

19 (1.2) |

16 (1.2) |

3 (1) |

1 |

|

Minor and major bleeding (%) |

29 (1.8) |

17 (1.3) |

12 (4) |

0.006 |

|

Stroke (%) |

9 (0.6) |

8 (0.6) |

1 (0.4) |

1 |

|

Repeat revascularization (%) |

6 (0.4) |

4 (0.2) |

2 (0.6) |

0.3 |

|

Reinfarction (%) |

9 (0.6) |

5 (0.4) |

2 (0.6) |

0.6 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Sex Difference in Clinical Outcomes

In-hospital clinical outcomes were shown in Table 6. The bleeding complications were high in the female group (1.3 vs. 4%, p-0.006). There were no significant differences in in-hospital mortality and other MACE events.

Discussion

Our study showed that women admitted for PCI were on an average of 2.8 years older than men that is inconsistent with previous studies published.14 15 This could be due to the protective role of circulating estrogens in younger women. The cardioprotective actions of estrogen are vasodilatation, reduced reactive oxidative stress, and fibrosis.16

DM and HTN were more prevalent in women when compared with men. Even though DM might affect men and women equally females are highly impacted by its consequences. Premenopausal diabetic women lose protection against heart disease.17 A study also reported that the diabetic women who presented with ACS had 36.9% mortality when compared with euglycemic women presenting with ACS 20.2%.18 Women aged ≥55 years have a higher prevalence of HTN than men, indicating the loss of arterial elasticity.19 20 Endogenous estrogens maintain vasodilation and contribute to blood pressure control in premenopausal women.21 During the menopause transition, the rise in systolic blood pressure is due to a decline in estrogen levels. Postmenopause, there is an upregulation of the renin-angiotensin system and increased plasma renin activity.22 With higher systolic blood pressure, the risk of coronary heart disease increases. Systolic blood pressure of at least 140 mm Hg increases coronary heart disease risk by 37% and for stroke by 86% in women.23

Increasing body weight is associated with increased coronary risk and fourfold increased risk in cardiovascular events in the heaviest category women compared with lean women.24

Few studies reported that truncal obesity and increased BMI as independent risk factors in young female patients with coronary artery disease (CAD). For predicting premature CAD, the sagittal abdominal diameter to skin fold ratio seems to be a good indicator.25

Clinical presentation of ACS differs between men and women. Women commonly presented with unstable angina compared with men.

From “bench to beyond premature ACS” study, irrespective of the type of ACS, chest pain is the most prevalent symptom among both sexes. However, women were more likely to present with diverse symptoms.26 They generally present with pain in the upper back, arm, neck, or jaw, and also as indigestion, nausea, vomiting, and palpitations. Shoulder pain and arm pain are twice as predictive of an ACS diagnosis in women compared with men27

The rate of thrombolysis is also less among women in our study. In a pooled analysis of 22 trials, 6,763 STEMI patients were randomized to primary PCI versus thrombolytic and found that women had lower 30-day mortality in primary PCI regardless of the time of presentation.28 Because of multiple relative contraindications for thrombolysis in women, treating physicians are reluctant to use thrombolytic therapy for STEMI in women.2 Another important observation in our study is that bleeding rates are higher among females. GUTSO-I trial reported that bleeding risk increased by 1.43-fold in women and showed higher risk of bleeding complications.29

The mortality due to CVD is the leading cause of death in women worldwide and higher among women when compared with men30 there is no significant difference in mortality noted in our study, perhaps due to the inequality in sample size. Kerala ACS registry also showed among 25,748 ACS patients, 5,825 were women, and there was no difference in the outcome of death, reinfarction, or stroke between both genders.31 Detection and management of coronary heart disease (DEMAT) registry also showed similar results.32

Though there is no significant mortality difference, bleeding events are significantly higher in women in our study that is consistent with other studies. Higher rates of bleeding after MI are seen in women than men.33 Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) trial showed that bleeding risk increased by 43% in women during hospitalization. PCI in women showed a significantly higher incidence of in-hospital major bleeding in other studies34 35

Conclusion

Our single-center study among patients undergoing PCI showed that women with ACS present at a later age compared with men and have a higher prevalence of risk factors like DM and HTN. Though there is no gender-based difference in in-hospital mortality after PCI, women have an increased risk of bleeding. Larger studies are needed to confirm this study's findings.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Authors do not have any conflict of interest.

References

- More similarities than differences: an international comparison of CVD mortality and risk factors in women. Health Care Women Int. 2008;29(01):3-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute myocardial infarction in women: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(09):916-947.

- [Google Scholar]

- [Effects of estrogens and progestogens on the lipid profile in postmenopausal hypogonadism] Ginecol Obstet Mex. 2001;69:351-354. [in Spanish]

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge attitudes, and beliefs regarding cardiovascular disease in women: the women's heart alliance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(02):123-132.

- [Google Scholar]

- Symptom presentation of women with acute coronary syndromes: myth vs reality. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(22):2405-2413.

- [Google Scholar]

- A clinical trial comparing primary coronary angioplasty with tissue plasminogen activator for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(23):1621-1628. [published erratum appears in N Engl J Med 1997;337(4):287]

- [Google Scholar]

- Endothelial erosion of plaques as a substrate for coronary thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115(03):509-519.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coronary heart disease mortality declines in the United States from 1979 through 2011: evidence for stagnation in young adults, especially women. Circulation. 2015;132(11):997-1002.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trends in acute myocardial infarction in young patients and differences by sex and race, 2001 to 2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(04):337-345.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hemorrhagic events during therapy with recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator, heparin, and aspirin for acute myocardial infarction. Results of the thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI), phase II trial. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(04):256-265.

- [Google Scholar]

- American College of Cardiology key data elements and definitions for measuring the clinical management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes. A report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Acute Coronary Syndromes Writing Committee) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(07):2114-2130.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115(17):2344-2351.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sex-Related Differences in Outcomes for Patients With ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI): A Tamil Nadu-STEMI Program Subgroup Analysis. Heart Lung Circ. 2021;30(12):1870-1875.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gender difference in risk factor profiles in patients referred for coronary angiogram. Ind J Cardiovasc Dis Journal in Women (IJCD). 2016;1(02):15.

- [Google Scholar]

- The protective role of estrogen and estrogen receptors in cardiovascular disease and the controversial use of estrogen therapy. Biol Sex Differ. 2017;8(01):33.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sex differences in cardiovascular and total mortality among diabetic and non-diabetic individuals with or without history of myocardial infarction. Diabetologia. 2005;48(05):856-861.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of diabetes on mortality after the first myocardial infarction. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(01):69-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perspectives on systolic hypertension. The Framingham study. Circulation. 1980;61(06):1179-1182.

- [Google Scholar]

- Systolic blood pressure and risk of cardiovascular diseases in type 2 diabetes: an observational study from the Swedish national diabetes register. J Hypertens. 2010;28(10):2026-2035.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coronary artery disease in young females: current scenario. Ind J Cardiovasc Dis Women-WINCARS. 2017;2(03):39-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sex differences in acute coronary syndrome symptom presentation in young patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(20):1863-1871.

- [Google Scholar]

- The economic burden of angina in women with suspected ischemic heart disease: results from the National Institutes of Health–National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. Circulation. 2006;114(09):894-904.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does time matter? A pooled analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing primary percutaneous coronary intervention and in-hospital fibrinolysis in acute myocardial infarction patients. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(07):779-788.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparisons of characteristics and outcomes among women and men with acute myocardial infarction treated with thrombolytic therapy. GUSTO-I investigators. JAMA. 1996;275(10):777-782.

- [Google Scholar]

- Heart disease and stroke statistics–2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(04):e29-e322.

- [Google Scholar]

- Presentation, management, and outcomes of 25 748 acute coronary syndrome admissions in Kerala, India: results from the Kerala ACS Registry. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(02):121-129.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association between gender, process of care measures, and outcomes in ACS in India: results from the detection and management of coronary heart disease (DEMAT) registry. PLoS One. 2013;8(04):e62061.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127(04):e362-e425. [published correction appears in Circulation. 2013;128:e481]

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of major bleeding in acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Eur Heart J. 2003;24(20):1815-1823.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sex differences in major bleeding with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors: results from the CRUSADE (Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines) initiative. Circulation. 2006;114(13):1380-1387.

- [Google Scholar]