Translate this page into:

Novel Variations in β-Myosin Heavy-Chain Gene (β-MYH7) and Its Association in South Indian Women with Cardiomyopathies

Deepa Selvi Rani Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology Uppal Road, Hyderabad 500 007, Telangana India deepa@ccmb.res.in; thangs@ccmb.res.in

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Background Mutations in β-MYH7 gene is a main genetic cause of cardiomyopathy and sudden cardiac arrest, yet the molecular mechanisms have not been fully understood.

Objectives To identify variations in β-MYH7 gene and their possible mechanistic role in cardiomyopathies among Indian women.

Methods We sequenced all exons and their flanking regions of the β-MYH7 gene in 188 Indian women consisting of 33 hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), 48 dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), and 107 healthy controls.

Results Our study showed 21 variations in β-MYH7 gene, including 7 novel mutations. In addition, we compared this dataset with our previously studied datasets of seven other sarcomere genes (ACTC, TNNT2, MYL2, MYBPC3, TPM1, TNNI3, and MYL3) and found no causative mutation, confirming the nonexistence of compound heterozygosity. Interestingly, we detected a Val431Met mutation exclusively in patients, and its pathogenicity has been predicted using the protein homology model. In native, Val431 is evolutionarily conserved across many species. In the homology model, mutant Met431 gets further buried in the hydrophobic core by creating an aberrant hydrophobic interaction with Leu352. As a result, it probably reduces the spatial distances between other hydrophobic interactions in the hydrophobic core that may produce steric hindrance and strain. It may lead to deviation in the structure (root means square deviation [RMSD] of ~3.9), and might possibly causing the cardiac remodeling and cardiomyopathy.

Conclusion We identified a novel Val431Met mutation, exclusively in patients, and its homology model p.Met431 has profoundly increased the mechanistic understanding of disease specifically in personalized medicine, to block/inverse/diminish the disease phenotype.

Keywords

β-MYH7 gene

homology model

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

dilated cardiomyopathy

cardiomyopathy

Introduction

South Asia has the highest proportion of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), including heart attacks and strokes of any region globally,1 probably due to their lifestyle and genetic architecture.2 Cardiomyopathy is one of the CVDs, which changes the heart morphology and damages the heart pumping ability, and it consequently leads to heart failure and sudden cardiac arrest in all age groups, particularly in young children, adults, and competitive athletes.3 Two major types of cardiomyopathies are dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM); each has significant heritable components.4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 HCM is identified with left ventricular increased wall thickness, mostly the involvement of interventricular septum, myocardial fibrosis, myocyte disarray, and affects diastolic function. Although debated, the estimated occurrence of HCM is approximately 0.2% or 1:500.13 14 15 DCM is detected with left ventricular dilatation, myocardial fibrosis, systolic dysfunction, myocyte death, and expected occurrence of approximately 1:2,500.10 16 Clinical heterogeneity varies from asymptomatic to symptomatic that results in failure of heart and sudden heart attack.17 Heterogeneity occurs because of environmental impacts such as food habits and exercise or genetic impacts due to modifying effects of genetic materials or the existence of more than one disease-causing mutations in patients.15 18 19 20 21 It has been well established that a mutation in sarcomeric genes can cause cardiomyopathies; In addition, compound mutations were also reported in a few HCM cases in association with early disease onset. Patients with double and triple mutations were with severe clinical symptoms because of the compound effect.17 18 19 20 21 22 Yet the molecular mechanisms for SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) that cause the diseases have not been fully understood.7

Though cardiomyopathies are the disease common for both men and women, there are substantial data indicating that sex bias in disease manifestation, severity, prevalence, and prognosis under the sociocultural and psychological influence. A cohort study consisting of 969 HCM patients showed a high incidence of disease in men than women.23 During athletic training, male athletes are found to develop a high degree of hypertrophy and sudden cardiac death (SCD) than females.24 25 A study based on the echocardiographic features revealed a high prevalence of HCM phenotype in men, however, almost an equal prevalence of both HCM and DCM phenotypes in women.26 Estrogen showed a profound protective effect in women with CVDs.27 Particularly in Takotsubo’s cardiomyopathy, there is a transient apical and medial left ventricular ballooning without coronary artery lesions, which arises exclusively in postmenopausal women and are typically initiated by physical or mental strain caused by repetitive stresses.28

Many studies have demonstrated a gender difference in clinical presentations, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention.29 Sadly, many women may not always understand the caution and indication signs of a cardiac arrest. An analysis was performed on 515 women patients who experienced an episode or more heart failures disclosed that approximately 43% had not experienced any type of classic signs such as palpitation, arrhythmias, chest pain, shortness of breath, or pressure during the heart attack.30 In the absence of classic signs, women have experienced some peculiar symptoms, such as extreme tiredness, vomiting, dizziness, indigestion, nausea, neck pain, back pain, etc.31 The American Heart Association (AHA, 2011) suggest that a CVD is no more man’s disease,32 33 34 and deaths due to CVD in women have surpassed those in men.32 In women, the diagnoses are mostly established after the onset; however, in men, the diagnoses are made normally during routine medical examinations. Therefore, it is a major reason that average age at disease diagnosis in men is considerably less than in women.23 In general, women may not understand symptoms correctly and moreover give much importance for those like men, because the symptoms are often nonspecific, such as giddiness, nausea, extreme tiredness, indigestion, vomiting, and back and neck pain. Therefore, a disease manifestation in women might be either misunderstood or unnoticed. Still, many questions are unanswered, and further researches in women are certainly needed. Many studies in female patients with different types of cardiomyopathies were performed in western countries; however, it is lacking in India. Hence, we performed the analyses in β-MYH7 gene of both men and women with cardiomyopathies from southern Indian and deposited in (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/snp_viewBatch.cgi?sbid=1062022) dbSNP data bank (unpublished data—men’s data under review). Here, we presented only the female patients’ data because this journal is specific for women. Moreover, we are keen on increasing awareness among women about the prevalence of CVD and to educate about a disease and its consequences. Therefore, in this study, we have presented the data of β-MYH7 gene variations observed in 81 female patients consisting of 33 HCM and 48 DCM along with 107 healthy control women from the same ethnic background.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Statement and Samples Collection

In this study, we have collected blood samples from 33 HCM and 48 DCM female patients with their informed written consents along with 107 healthy ethnically matched voluntary women controls (Table 1) from south India. The Institutional Ethical Committees of CARE Hospitals, and CSIR-Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB), Hyderabad, Telangana have approved the study, and it follows the ethics of Declaration of Helsinki, the World Medical Association. Blood samples of these women are collected, transthoracic 2D echocardiography after they have undergone the 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) and Doppler studies.

|

Baseline characteristics |

HCM (n = 33) |

DCM (n = 48) |

Controls (n = 107) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; ECG, electrocardiogram; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD, left ventricular end-systolic dimension; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SCD, sudden cardiac death. |

|||

|

Age (y) |

49 ± 12 |

49 ± 8 |

50 ± 0.2 |

|

Consanguinity (%) |

80.25 |

30.61 |

0 |

|

Diet: non-veg (%) |

85.80 |

81.63 |

65 |

|

Diabetes (%) |

1.85 |

17.69 |

0 |

|

Hypertension (%) |

4.94 |

27.21 |

22 |

|

Dyspnea or shortness of breath (%) |

67 |

66.7 |

0 |

|

Angina pectoris (chest pain) (%) |

56.8 |

57.2 |

0 |

|

Syncope (fainting) (%) |

31.9 |

32.1 |

0 |

|

Abnormal ECG (%) |

47.4 |

47.6 |

0 |

|

LVEDD (mm) |

36 ± 6.8 |

67 ± 10 |

51.3 ± 2.7 |

|

LVESD (mm) |

21.3 ± 3.7 |

54 ± 7.7 |

32.1 ± 1.2 |

|

Septum (mm) |

23.2 ± 4.2 |

6 ± 2.7 |

9 ± 0.2 |

|

Family history (%) |

82 |

79 |

0 |

|

Sudden cardiac death (%) |

15.8 |

14.2 |

0 |

|

LVEF (%) |

49 ±7 |

30 ± 6.6 |

65.2 ± 6.1 |

|

NYHA class III and IV |

34.8 |

35.2 |

0 |

Genetic Analysis

We screened for mutations in β-myosin heavy-chain β-MYH7 gene, using DNA extracted from patients and controls blood samples by a method described elsewhere.35

In Silico Analysis

Analysis of possible pathogenic effects of missense mutations is predicted using homology models along with the information from two bioinformatics tools: polymorphism phenotyping 2 (PolyPhen-2) and sorting intolerant from tolerant (SIFT). Homology models are constructed for two observed missense mutations using 3D template structure having 99% similarity obtained from RCSB (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structure) PDB,36 by SWISS-MODEL repository system (http://swissmodel.expasy.org).37 38

Results

We identified 21 genetic variations in β-MYH7 (Table 2), including 7 novel of which 2 (A423T and V431M) are single nucleotide substitution/ nonsynonymous/missense mutations in HCM and DCM patients; however, the A423T is also detected in a healthy control, but the V431M mutation is completely absent in 107 ethnically matched healthy controls (Table 2). We used the SIFT and PolyPhen-2 bioinformatics prediction tool to sort intolerant to tolerant or possibly/probably damaging to benign variants (Table 2). Apart from missense mutations, we identified a total of 16 silent or synonymous mutations (4 in both HCM and DCM, 4 in DCM, and remaining 8 are found to be polymorphic) (Table 2), 2 intronic variations are being detected exclusively in cases. Further, this study data are compared with our previous datasets of seven other sarcomere genes, MYL3, TPM1, ACTC, TNNI3, TNNT2, MYBPC3, and MYL2,8 14 35 39 40 41 42 and found no additional causative mutation suggesting nonexistence of compound heterozygosity.

|

S. No |

Chromosome position |

SS# No |

Major> Minor allele |

Location |

rs# No |

Amino acid |

PolyPhen2 |

SIFT |

CON |

HCM |

DCM |

Novel/Reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: CON, controls; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; SIFT, sorting intolerant from tolerant. Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/snp_viewBatch.cgi?sbid=1062022 |

||||||||||||

|

1 |

1423900942 |

1505811304 |

A>T |

Intron 7 |

rs606231314 |

– |

– |

– |

0 |

1 |

2 |

Novel |

|

2 |

1423900887 |

1505811306 |

G>A (IVS7–1G) |

Intron 7 |

rs606231315 |

SA |

– |

– |

0 |

0 |

1 |

Novel |

|

3 |

1423900794 |

974488077 |

C>T |

Exon 8 |

rs2069542 |

F244 |

– |

– |

1 |

3 |

5 |

Reported |

|

4 |

1423899060 |

974488074 |

C>T |

Exon 12 |

rs735712 |

G354 |

– |

– |

0 |

1 |

2 |

Reported |

|

5 |

1423898994 |

974488072 |

C>T |

Exon 12 |

rs2231126 |

D376 |

– |

– |

0 |

0 |

3 |

Reported |

|

6 |

1423898304 |

1505811312 |

G>A |

Exon 14 |

rs606231321 |

A423T |

Benign |

Damaging |

1 |

2 |

3 |

Novel |

|

7 |

1423898280 |

1505811313 |

G>A |

Exon 14 |

rs606231322 |

V431M |

Damaging |

Tolerated |

0 |

1 |

1 |

Novel |

|

8 |

1423897781 |

4915743 |

G>A |

Exon 15 |

rs3729813 |

K502 |

– |

– |

1 |

3 |

4 |

Reported |

|

9 |

1423896897 |

Reported |

A>G |

Exon 16 |

CP025164 |

Q595 |

– |

– |

1 |

1 |

2 |

Reported |

|

10 |

1423896894 |

1505811316 |

G>A |

Exon 16 |

rs606231325 |

K596 |

– |

– |

2 |

2 |

3 |

Novel |

|

11 |

1423896852 |

1505811317 |

G>A |

Exon 16 |

rs606231326 |

Q610 |

– |

– |

1 |

1 |

3 |

Novel |

|

12 |

1423896002 |

342383804 |

T>C |

Exon 18 |

rs145564868 |

N676 |

– |

– |

0 |

1 |

2 |

Reported |

|

13 |

1423895289 |

4041783 |

G>C |

Exon 19 |

rs1126421 |

G682 |

– |

– |

1 |

2 |

3 |

Reported |

|

14 |

1423895045 |

1505811325 |

G>A |

Intron 19 |

rs606231333 |

– |

– |

– |

0 |

2 |

3 |

Novel |

|

15 |

1423895006 |

1067544334 |

G>A |

Exon 20 |

rs148650290 |

A728 |

– |

– |

0 |

0 |

2 |

Reported |

|

16 |

1423895003 |

Reported |

C>A |

Exon 20 |

CM057344 |

A729 |

– |

– |

0 |

1 |

1 |

Reported |

|

17 |

1423894132 |

1505811299 |

G>A |

Exon 22 |

rs397516154 |

E875 |

– |

– |

0 |

1 |

2 |

Reported |

|

18 |

1423893287 |

4041786 |

C>T |

Exon 23 |

rs1041957 |

A917 |

– |

– |

2 |

3 |

3 |

Reported |

|

19 |

1423892888 |

974488065 |

T>C |

Exon 24 |

rs7157716 |

I989 |

– |

– |

0 |

0 |

2 |

Reported |

|

20 |

1423892819 |

990927921 |

C>T |

Exon 24 |

rs145379951 |

A1012 |

– |

– |

0 |

0 |

1 |

Reported |

|

21 |

1423891481 |

1350190204 |

G>A |

Exon 25 |

rs45540831 |

A1051 |

– |

– |

1 |

3 |

2 |

Reported |

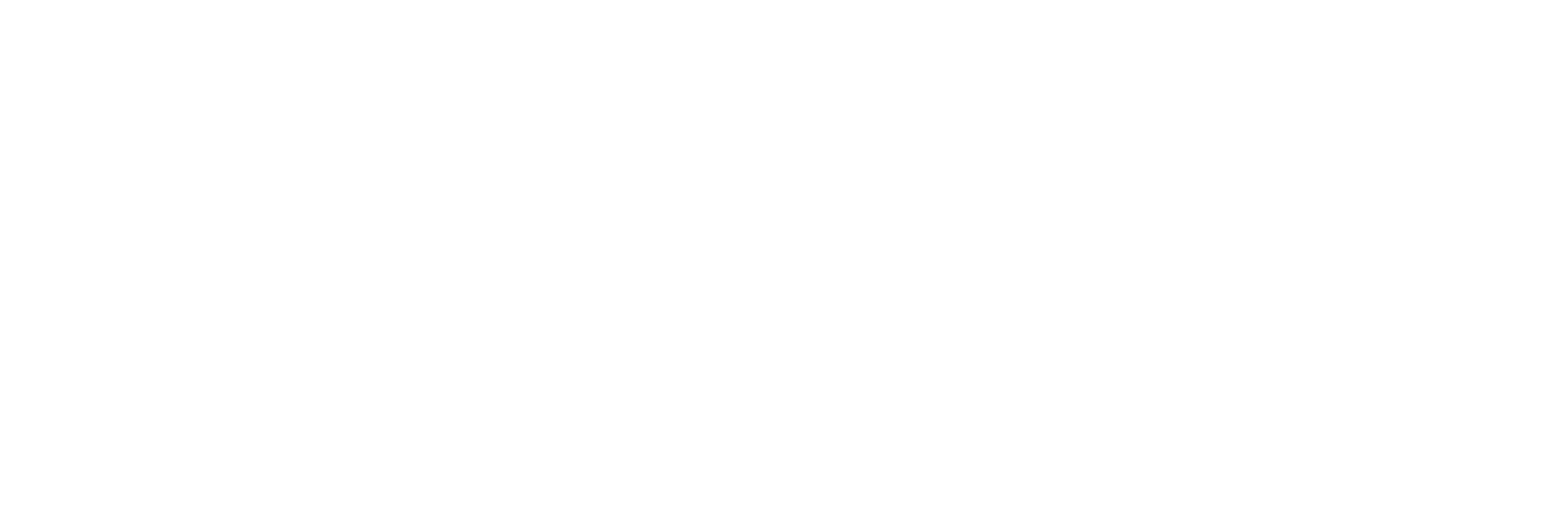

The age of onset for HCM was about 37 years; however, the age of onset for DCM cases was about 40 years. Our study revealed a V431M single nucleotide substitution in both HCM and DCM patients and completely absent in controls. The native Val431 is evolutionarily conserved across species. The pathogenicity of V431M is predicted using a protein homology model. A 45-year-old DCM patient with V431M mutation also carried A423T single nucleotide substitutions along with a synonymous F244 (homozygous) and a novel splice acceptor variation (IVS7–1G) G>A), indicating the phenotypic plasticity (Fig. 1; Table 2). All these four mutations have also been detected in her 15-year-old daughter who showed marginal DCM phenotype (asymptomatic). The proband showed dilated left ventricle and decreased contractile function with less ejection fraction of 25%. SCD of her sister at the age of 65 years (asymptomatic) was noticed as an evidence of inheritary component. Therefore, the disease onset, symptoms, and severities vary greatly in the family itself, suggesting environmental influence such as sociocultural and psychological factors that are being involved.

-

Fig. 1 Electropherograms (arrows) showing few SNPs of β-MYH7 gene observed in this study. A splice acceptor variation (IVS7–1G) G>A; 2 nonsynonymous mutations GCC→ACC (A423T) and GTG→ATG (V431M); and three synonymous mutations A728 (G>A), F244 (C>T), G354 (C>T) in south Indian female patients with both HCM and DCM.

Fig. 1 Electropherograms (arrows) showing few SNPs of β-MYH7 gene observed in this study. A splice acceptor variation (IVS7–1G) G>A; 2 nonsynonymous mutations GCC→ACC (A423T) and GTG→ATG (V431M); and three synonymous mutations A728 (G>A), F244 (C>T), G354 (C>T) in south Indian female patients with both HCM and DCM.

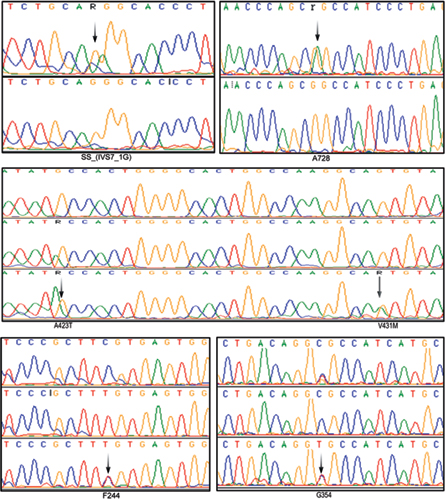

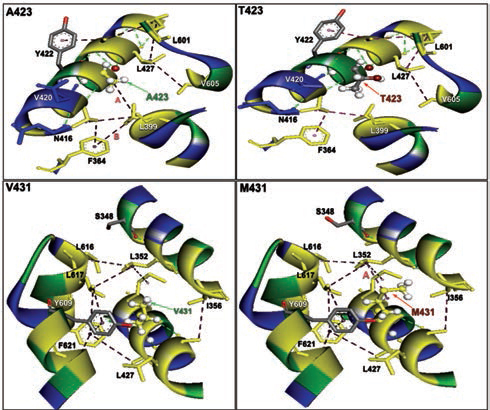

Furthermore, homology models are built for these two nonsynonymous mutations, A423T and V431M using 3D template structure having 99% similarity and analyzed against a native protein. In a native p.A423 protein, the hydrophobic Ala423 is being held by hydrophobic interaction with Leu399 and that in turn forms a second hydrophobic interaction with Phe364 in the α-helix (Fig. 2), but located near the surface. However, substitution of polar Thr423 has destroyed both the hydrophobic interactions (Ala423:Leu399 and Leu399:Phe364) formed by native Ala423 (Fig. 2), and as a result, the mutant polarThr423 laid on the surface (Fig. 2). As expected, the superimposed structure of mutant p.T423 homology model with the template has not shown much deviation (RMSD ~1.17Aº) (Fig. 3).

-

Fig. 2 The nonbonding (NB) interactions at the mutation site of two β-myosin mutant homology model versus native. A423T: NB interactions in mutant p.T423 homology model destroyed a hydrophobic bond formed between alanine 423 and Leucine 399 having a bond distance of 4.997 and labeled as A. V431M: NB interactions in mutant p.M431 homology model: NB interactions at 431 valine substituted with methionine at 431 destroyed a conventional hydrogen bond A formed between valine 431 and alanine 428 with a bond length of 3.3996 and labeled as A, whereas a hydrophobic bond was created in mutant between leucine 352 and methionine 431 with a bond distance of 4.626 labeled as B.

Fig. 2 The nonbonding (NB) interactions at the mutation site of two β-myosin mutant homology model versus native. A423T: NB interactions in mutant p.T423 homology model destroyed a hydrophobic bond formed between alanine 423 and Leucine 399 having a bond distance of 4.997 and labeled as A. V431M: NB interactions in mutant p.M431 homology model: NB interactions at 431 valine substituted with methionine at 431 destroyed a conventional hydrogen bond A formed between valine 431 and alanine 428 with a bond length of 3.3996 and labeled as A, whereas a hydrophobic bond was created in mutant between leucine 352 and methionine 431 with a bond distance of 4.626 labeled as B.

-

Fig. 3 Two mutant homology models (p.T423 and p.M431) are superimposed with 3D native template structure and calculated root means square deviations (RMSD). The whole native structures (helix, β-sheets, and turns) were shown in yellow color, whereas each of the eight mutant homology models; the helixes were in red, β-sheets were in cyan and turns were in ash color.

Fig. 3 Two mutant homology models (p.T423 and p.M431) are superimposed with 3D native template structure and calculated root means square deviations (RMSD). The whole native structures (helix, β-sheets, and turns) were shown in yellow color, whereas each of the eight mutant homology models; the helixes were in red, β-sheets were in cyan and turns were in ash color.

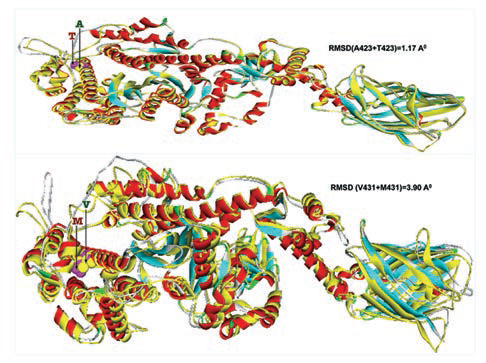

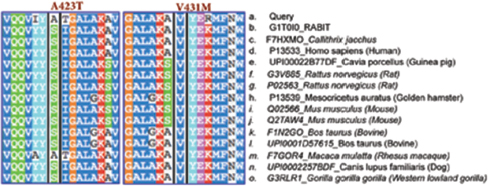

In the native protein, the valine residue at 431 is evolutionarily conserved across many species (Fig. 4); therefore, this mutation is predicted to have a significant impact on disease phenotype. In a native protein, the hydrophobic val431 is located in the hydrophobic core. In mutant protein, the substitution of met431 creates an additional aberrant hydrophobic interaction with Leu352 and gets buried within the hydrophobic core (Fig. 2), which also further decreases the spatial distances between other hydrophobic interactions in the hydrophobic core (e.g., the hydrophobic interaction distance between the Leu427 and Leu601 from 5.23 in native to 4.88 in mutant and that creates the strain in the mutant protein structure), which led to more deviation in the mutant protein structure (RMSD of ~3.9Aº) (Fig. 3). Therefore, in this study, we predict that the deviated structure is possibly the cause for cardiac remodeling and change the morphology of the heart into HCM and DCM phenotype. The V431M in the DCM patient along with three other additional variations (A423T, F244, IVS7–1G) as contributing factors for the DCM disease phenotype shows the phenotypic plasticity in this family. Moreover, the DCM patient attained menopause at the age of 44 years, and since then she has been suffering from more severe complications. Therefore, a decline in the natural hormone estrogen may be a matter of concern.

-

Fig. 4 Of the two A423T and V431M single residue substitutions (SRSs) in the motor head domain of β-MYH7 gene, the V431 is highly conserved across many species, including (A) Query (Homo sapiens: human), (B) G1T0I0—Oryctolagus cuniculus (rabbit), (C) F7HXMO—Callithrix jacchus (common marmoset), (D) P13533—Homo sapiens (human), (E) UPI00022B77DF—Cavia porcellus (guinea pig), (F) G3V885—Rattus norvegicus (rat), (G) P02563—Rattus norvegicus (rat), (H) P13539—Mesocricetus auratus (golden hamster), (I) Q02566—Mus musculus (mouse), (J) Q2TAW4—Mus musculus (mouse), (K) FIN2GO—Bos taurus (bovine), (L) UPI0001D57615—Bos taurus (bovine), (M) F7GOR4—Macaca mulatta (rhesus macaque), (N) UPI0002257BDF—Canis lupus familiaris (dog), (O) G3RLR1—Gorilla gorilla gorilla (Western lowland gorilla), however, A423 is not.

Fig. 4 Of the two A423T and V431M single residue substitutions (SRSs) in the motor head domain of β-MYH7 gene, the V431 is highly conserved across many species, including (A) Query (Homo sapiens: human), (B) G1T0I0—Oryctolagus cuniculus (rabbit), (C) F7HXMO—Callithrix jacchus (common marmoset), (D) P13533—Homo sapiens (human), (E) UPI00022B77DF—Cavia porcellus (guinea pig), (F) G3V885—Rattus norvegicus (rat), (G) P02563—Rattus norvegicus (rat), (H) P13539—Mesocricetus auratus (golden hamster), (I) Q02566—Mus musculus (mouse), (J) Q2TAW4—Mus musculus (mouse), (K) FIN2GO—Bos taurus (bovine), (L) UPI0001D57615—Bos taurus (bovine), (M) F7GOR4—Macaca mulatta (rhesus macaque), (N) UPI0002257BDF—Canis lupus familiaris (dog), (O) G3RLR1—Gorilla gorilla gorilla (Western lowland gorilla), however, A423 is not.

Discussion

The clinical correlation found in both HCM and DCM patients are as follows: both the patients were from consanguineous family showed abnormal ECG; symptoms of dyspnea, angina pectoris, and syncope (Table 1). Sudden cardiac arrests were noted in both HCM and DCM families. The secondary factors such as hypertension, diabetes (Table 1), and body mass index (BMI) have studied, and it was found that the prevalence of cardiac impairment has not varied with BMI. Most of HCM (80.25%) and a few DCM (30.6%) cases are from consanguineous families (Table 1).

Structure of a protein determines its function. If any structural change occurs in a protein at any level, it may affect its function.43 The accurate 3D protein structure is basically governed by different kinds of molecular interactions; the hydrophobic interactions aggregate in solution to form well-packed folded protein nuclear core, and the polar amino acids are located on the folded protein surface by hydrogen bonding. Therefore, understanding the molecular interactions is the most important.44 Commonly when a protein folds, few other residues along with hydrophobic residues are also trapped in the protein nuclear core, more specifically without the contact of water, which generally constitute approximately 81% of the hydrophobic residues, approximately 63% of the hydrophilic residues, approximately 54% of the charged residues, and approximately 70% peptide groups that were shown to be trapped in 3D protein conformation.45 We learned from the mutant p.Met431 protein homology model that the disturbed hydrophobic core due to Met431 substitution may be the cause for structural deviation. Therefore, we predict that this deviation has partaken in cardiac remodeling and changes the morphology of the heart into HCM and DCM phenotypes; however, the DCM patient carried three additional idiopathic variations ([A423T, synonymous F244 [homozygous], and one splice site [IVS7–1G]) as contributing factors for the DCM phenotypic plasticity in this family. Moreover, this study has profoundly increased the mechanistic understanding of disease; thus, each patient can be treated specifically based on their mutation.

It has been well proven that the aberrant form of the protein itself appears to be the pathogenic agent, implicating in a wide range of increasingly debilitating and highly prevalent diseases.46 Folding and unfolding are crucial ways of regulating biological activity. It is well known that the missense mutations trigger nonfunctional misfolded proteins to get accumulated in the form of oligomers, amyloid fibrils, and cause diseases, which includes, spongiform encephalopathy, type 2 diabetes, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s prion disease, and a wide range of other disorders.47 In sickle cell anemia, the pathogenicity is due to a missense mutation E6V in β-globin, which increases the hydrophobicity, which alters the structure of red blood cell (RBC) from round to sickle shape, because of which the sickle cells stick to each other to avoid the aqueous environment and that causes the disease phenotype.48 The p.M431 mutant homology model has profoundly increased the mechanistic understanding of disease specifically in personalized medicine, to block or reverse or dismiss the disease phenotype by which each missense mutation can be treated exclusively. In future, we would like to analyze more number of women with cardiomyopathy. We will be interested to work on Takotsubo’s cardiomyopathy and coronary artery disease that are found to have high frequency among women. Moreover, we are keen on increasing awareness among women about the prevalence of CVD and to educate about a disease and its consequences.

Conclusion

In the homology model, the mutant Met431 creates an aberrant hydrophobic interaction with Leu352 and gets buried in the hydrophobic core. As a result, it probably reduces the spatial distances between other hydrophobic interactions in the hydrophobic core that produces strain and deviation in the structure (RMSD of ~3.9). We predict that the deviated structure is possibly the cause of cardiac remodeling and cardiomyopathy.

Author Contributions

Experiments designed and conceived by: DSR and KT

Genetic experiments and in silico analyses performed by: DSR

Clinical evaluation of cases performed by: PN and CN

Paper written by: DSR

Critical suggestions provided by: KT

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge each patient, their family members, and healthy controls for willingly contributed their blood samples for analyses.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Funding D. S. Rani and K. Thangaraj are salaried through CSIR_CCMB, Hyderabad, India. CSIR/CCMB funded this project, however, they have not been involved in this study design, data collection, analysis, preparation of the manuscript, and decision to publish.

References

- Epidemiology and causation of coronary heart disease and stroke in India. Heart. 2008;94(01):16-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sudden death in young competitive athletes. Clinical, demographic, and pathological profiles. JAMA. 1996;276(03):199-204.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel cardiac troponin T mutation as a cause of familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2001;104(18):2188-2193.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mutations of the beta myosin heavy chain gene in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: critical functional sites determine prognosis. Heart. 2003;89(10):1179-1185.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mutations in the genes for cardiac troponin T and alpha-tropomyosin in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(16):1058-1064.

- [Google Scholar]

- The genetic basis for cardiomyopathy: from mutation identification to mechanistic paradigms. Cell. 2001;104(04):557-567.

- [Google Scholar]

- A novel arginine to tryptophan (R144W) mutation in troponin T (cTnT) gene in an Indian multigenerational family with dilated cardiomyopathy (FDCM) PLoS One. 2014;9(07):e101451.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sarcomere protein gene mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy of the elderly. Circulation. 2002;105(04):446-451.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mutations in sarcomere protein genes as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(23):1688-1696.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of genetics in the clinical evaluation of cardiomyopathy. JAMA. 2009;302(22):2471-2476.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a general population of young adults. Echocardiographic analysis of 4111 subjects in the CARDIA Study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults. Circulation. 1995;92(04):785-789.

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of arginine to glutamine substitution at 98, 141 and 162 positions in troponin I (TNNI3) associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy among Indians. BMC Med Genet. 2012;13:69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Progress with genetic cardiomyopathies: screening, counseling, and testing in dilated, hypertrophic, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2(03):253-261.

- [Google Scholar]

- Familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Clinical and genetic characteristics. Herz. 2012;37(08):822-829.

- [Google Scholar]

- Myosin binding protein C mutations and compound heterozygosity in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(09):1903-1910.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: distribution of disease genes, spectrum of mutations, and implications for a molecular diagnosis strategy. Circulation. 2003;107(17):2227-2232.

- [Google Scholar]

- Compound and double mutations in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: implications for genetic testing and counselling. J Med Genet. 2005;42(10):e59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical features and outcome of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy associated with triple sarcomere protein gene mutations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(14):1444-1453.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and genetic issues in dilated cardiomyopathy: a review for genetics professionals. Genet Med. 2010;12(11):655-667.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gender-related differences in the clinical presentation and outcome of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(03):480-487.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of sex on the “Athlete’s Heart” in trained cyclists. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13(05):475-478.

- [Google Scholar]

- The upper limit of physiological cardiac hypertrophy in elite male and female athletes: the British experience. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;92:592-597. (4-5)

- [Google Scholar]

- Gender-related risk of myocardial involvement in systemic amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2008;15(01):40-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hormone replacement therapy and cardioprotection: what is good and what is bad for the cardiovascular system? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1092:341-348.

- [Google Scholar]

- Takotsubo cardiomyopathy—the current state of knowledge. Int J Cardiol. 2010;142(02):120-125.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proteomics in cardiovascular diseases: unveiling sex and gender differences in the era of precision medicine. J Proteomics. 2018;173:62-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Women’s early warning symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003;108(21):2619-2623.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gender differences in symptom presentation associated with coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(04):396-399.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Heart of 25 by 25: achieving the goal of reducing global and regional premature deaths from cardiovascular diseases and stroke: a modeling study from the American Heart Association and World Heart Federation. Glob Heart. 2016;11(02):251-264.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women—2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(11):1243-1262.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac troponin T (TNNT2) mutations are less prevalent in Indian hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients. DNA Cell Biol. 2012;31(04):616-624.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structural basis for drug-induced allosteric changes to human. β-cardiac myosin motor activityNat Commun. 2015;6:7974.

- [Google Scholar]

- SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W252-8. (Web Server issue)

- [Google Scholar]

- Automated comparative protein structure modeling with SWISS-MODEL and Swiss-Pdb-Viewer: a historical perspective. Electrophoresis. 2009;30(01):S162-S173.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coexistence of digenic mutations in both thin (TPM1) and thick (MYH7) filaments of sarcomeric genes leads to severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a South Indian FHCM. DNA Cell Biol. 2015;34(05):350-359.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic variations of. α-cardiac actin and cardiac muscle LIM protein in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in South IndiaExp Clin Cardiol. 2012;17(01):26-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- A common MYBPC3 (cardiac myosin binding protein C) variant associated with cardiomyopathies in South Asia. Nat Genet. 2009;41(02):187-191.

- [Google Scholar]

- a complete absence of missense mutation in myosin regulatory and essential light chain genes of south Indian hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies. Cardiology. 2018;141(03):156-166.

- [Google Scholar]

- Conformational stability of globular proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15(01):14-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Forces contributing to the conformational stability of proteins. FASEB J. 1996;10(01):75-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:333-366.

- [Google Scholar]

- Amyloid-associated proteins alpha 1-antichymotrypsin and apolipoprotein E promote assembly of Alzheimer beta-protein into filaments. Nature. 1994;372:92-94. 6501

- [Google Scholar]

- Gene mutations in human haemoglobin: the chemical difference between normal and sickle cell haemoglobin. Nature. 1957;180:326-328. 4581

- [Google Scholar]