Translate this page into:

Gender Differences in South Indians with Premature Coronary Artery Disease (< 40 Years)—Insights from the PCAD Registry

Vijay Kumar J. R., MD, DM Department of Cardiology, Sri Jayadeva Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences and Research Jayanagar 9th Block, Bannerghatta Road, Bengaluru 560069, Karnataka India dr.vijaykumarjr@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Introduction Coronary artery disease (CAD) follows a different pattern in women and men, more so in the young (< 40 years). The gender differences in the risk factors, clinical presentation and diagnosis need to be understood, so that appropriate and timely treatment can be given.

Objective The study contemplates to analyze the gender differences in the presence of major coronary risk factors, clinical presentation, diagnosis and immediate outcomes in patients who present with premature CAD (PCAD).

Patients and Methods We evaluated 1,062 consecutive registry patients who presented with diagnosis of PCAD between 2018 to 2019 at our institution after satisfying the inclusion criteria.

Results The study analyses 82 females and 980 males. The mean age of females was 35.4 ± 4.68 years and males was 34.2 ± 4.25 years. Males smoked more often (55.1%, p < 0.001). Females more often had abnormal BMI (84.1%, p < 0.001), increased waist-hip ratios (97.6%, p < 0.001), diabetes (35.4%, p < 0.001), dyslipidemia (17.1% vs. 11%) and hypertension (15.9% vs. 11.5%). STEMI was the most common presentation among males (80.4% vs. 71.9%). Majority of females (74.6%) presented 6 hours after index pain. NSTEMI was more common among females (20.7% vs. 16%). Single-vessel involvement was common in both sexes (84.1% in males and 85.2% in females). Obstructive CAD was less common in both groups.

Conclusions Conventional risk factors play a major role for CAD in Indians. Smoking was common in males and metabolic syndrome in females. Also, females had a higher threshold for seeking treatment and referral. Measures have to be taken for early diagnosis and referral of females. Recanalized and thrombotic coronaries were common, indicating predominant thrombus burden in the young

Keywords

conventional risk factors

recanalized coronaries

thrombus

gender differences

premature CAD

-

Abstract Image

Abstract Image

Introduction

Epidemiological transition has led to an increase of coronary artery disease (CAD) in the young. It is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity among both sexes, accounting for nearly one-third of total deaths.1 It has reached an epidemic proportion among Indians and accounts for higher death rate in women, regardless of their race or ethnicity.2

In Indians, the average age of first myocardial infarction (MI) has decreased by 20 years. Among Indians, CAD is double that of Americans and also several folds higher than other Asians.3 Among Asian Indians, about half of all MI occurs under the age of 50 and 25% under the age of 40. Indian ethnicity has now been demonstrated to be a risk factor by itself.4 Although young patients have good prognosis with predominance of single-vessel disease (SVD), there is significant morbidity, psychological stress, and financial burden.

Conventional risk factors, including family history, continue to play pivotal role in premature CAD (PCAD) in Indians. Elevated triglyceride (TGC) level is a strong predictor of CAD in women compared with men. It has been shown that an increase in TG level of 90 mg/dl increases the CAD risk by 75% in women and 30% in men.5 Metabolic syndrome is a precursor of diabetes and CAD. This syndrome is particularly common among Indians; also, both diabetes and metabolic syndrome are equally prevalent in women. CAD is noted to be twice as common among women with diabetes than those without. In the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III), diabetes is regarded as a CAD risk equivalent.6 Diabetes is a stronger risk factor for CAD in women than in men, with a 3- to 7-fold higher CAD incidence and mortality compared with 2- to 3- fold in men. Diabetes increases the risk of heart failure by eight times in women compared with four times in men. Diabetes also eliminates the protective effects of estrogens and removes the normal sex difference in the prevalence of CAD.7

Hypertension confers a four-time higher risk of CAD in women versus three times in men.

Women have poorer prognosis and more adverse outcomes than men after myocardial infarction (MI), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). They are also more likely to die after a first MI compared with men. Among survivors, there is higher risk of recurrent MI, heart failure or death.8

There are various population studies highlighting demographic and socioeconomic cardiovascular (CV) risk factors in the young. There is paucity of data on PCAD, especially on gender differences in those aged below 40 years. Therefore, we have analyzed the gender differences in risk factors, clinical presentation and angiographic profile in Indian youth from the ongoing PCAD registry at our institute.

Objective

The present study contemplates to analyze the gender differences in the presence of major coronary risk factors, clinical presentation, angiographic profile and immediate outcomes in patients who present with PCAD aged ≤ 40 years.

Methods

We evaluated 1,062 consecutive patients who presented with diagnosis of PCAD (age ≤ 40 years) between 2018 to 2019 at our institution after satisfying the inclusion criteria. The presence of major coronary risk factors such as family history of CAD, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cigarette smoking and drug/substance abuse were recorded. The clinical presentation, angiographic findings and immediate outcomes were also recorded.

Inclusion Criteria

Patients who were aged < 40 years and presented with new onset ischemic heart disease, which was diagnosed by the following:

(1) Documented episode of acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

(2) Chronic stable angina (CSA) with documented evidence of CAD and who were treatment-naive were included.

Exclusion Criteria

(1) Patients with myocarditis, cardiomyopathies, and pulmonary embolism (PE).

(2) Patients with previous diagnosis of CAD, including CSA on treatment and also those on medications such as antiplatelets and statins for other reasons

(3) Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), liver failure, consumption of oral contraceptives, and steroids were excluded

STEMI was defined as ST-segment elevation in two contiguous leads with or without reciprocal ST-segment depression, NSTEMI as elevation of high-sensitivity troponin-T or CK-MB elevation, and unstable/CSA as ST-segment depression or T-wave inversion in two contiguous leads with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD).

Diabetes was defined as having a history of diabetes diagnosed and/or treated with medication and/or diet or fasting blood glucose 126 mg/dl or greater. Hypertension was defined as being prior diagnosed and/or treated with medication, diet and/or exercise and blood pressure greater than 140 mm Hg systolic or 90 mm Hg diastolic on at least two occasions.

Hyperlipidemia was defined as history of dyslipidemia diagnosed and/or treated by a physician or total cholesterol (TC) greater than 200 mg/dl, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) greater than or equal to 130 mg/dl, or high-density lipoprotein (HDL) < 40 mg/dl in males and < 50 mg/dl in females. A positive family history for CAD was defined as evidence of CAD in a first degree relative < 55 years for males and < 65 years for females. Overweight was defined as body mass index (BMI) of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2. Obesity was defined as BMI greater than 30kg/m2.Waist circumference of > 102 cm in males and > 88 cm in females was considered abnormal (NCEP-ATP-III criteria).6 High waist-hip ratio (WHR) was defined as > 0.9 in males and > 0.8 in females. All patients underwent coronary angiography either during their index admission or during follow-up. Significant stenosis was defined as > 70% stenosis in the coronaries (> 50% for left main coronary artery [LMCA]), insignificant disease as less than 70% stenosis or plaques in any of the coronary arteries.

Results

The study analyses 82 females and 980 males who were enrolled in the registry after satisfying the inclusion criteria.

Demographic and Risk Factor Characteristics

The mean age of females was 35.4 ± 4.68 years. The youngest female was 25 years. The mean age of males was 34.2 ± 4.25 years. The youngest male was 19 years. Among males, 55.1% of them were smokers, 1% were reformed smokers (p < 0.001). There were no women who smoked. No patients confirmed history of drug/substance abuse. Diabetes was noted in 35.4% females and 11.5% males. Hypertension was seen in 15.9% females and 11.5% males. Dyslipidemia was noted in 17.1% females and 11% males. The mean LDL in males was 116.93 ± 86.89, and in females, it was 109.76 ± 54.11; the mean HDL in males was 34.66 ± 11.04, and in females, it was 38.26 ± 22.88; the mean TC in males was 173.9 ± 49.93, and in females, it was 172.44 ± 64.78; the mean TGC in males was 172.11 ± 107.3, and in females, it was 179.22 ± 125.88.

Positive family history was noted in 13.4% females and 13.9% males. There were 48.8% females and 55.5% males from urban area. Majority of patients consumed a nonvegetarian diet, only 9.8% females and 7.2% males followed a vegetarian diet.

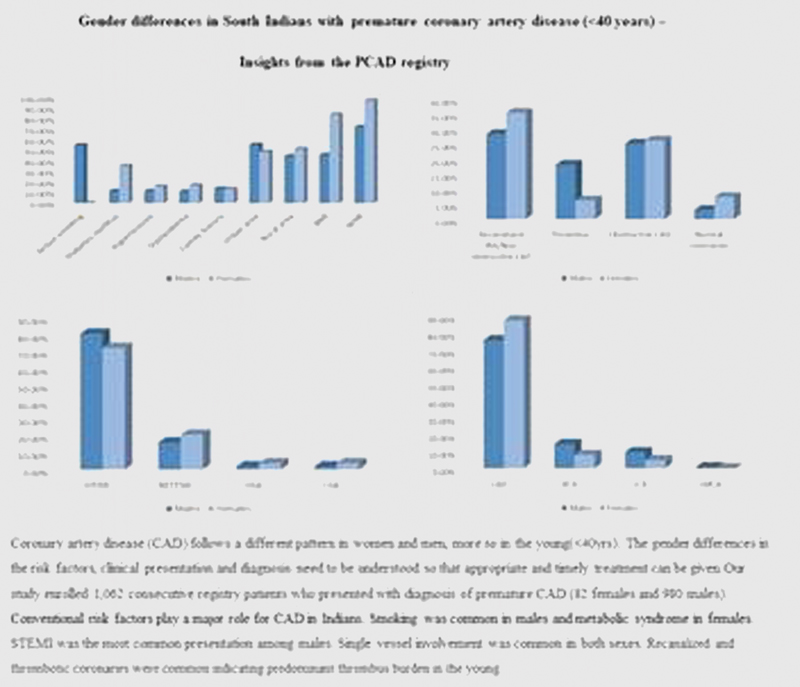

Among females, 15.9% had a normal BMI, 69.5% were overweight and 14.6% were obese. Among males, 52.6% had normal BMI, 37% were overweight, 8.9% were obese, and 1.5% were underweight. The average BMI in females was 25.1 and 23.4 in males. The WHR was high in 97.6% females and 72.3% males (as shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1).

|

Variables |

Male (n = 980) |

Female (n = 82) |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age |

34.17 ± 4.25 |

35.4 ± 4.68 |

|

|

Active smoking |

539 (55.1) |

0 (0) |

< 0.001 |

|

Diabetes mellitus |

113 (11.5) |

29 (35.4) |

< 0.001 |

|

Hypertension |

113 (11.5) |

13 (15.9) |

NS |

|

Dyslipidemia |

108 (11) |

14 (17.1) |

NS |

|

Family history |

136 (13.9) |

11 (13.4) |

NS |

|

Urban area |

543 (55.5) |

40 (48.8) |

NS |

|

Rural area |

436 (44.5) |

42 (51.2) |

|

|

BMI |

449 (45.9) |

69 (84.1) |

< 0.001 |

|

WHR |

708 (72.3) |

80 (97.6) |

< 0.001 |

|

ACS presentation |

|||

|

STEMI |

787 (80.4%) |

59 (71.9%) |

NS |

|

NSTEMI |

157 (16%) |

17 (20.7%) |

|

|

UA |

18 (1.8%) |

3 (3.7%) |

|

|

CSA |

18 (1.8%) |

3 (3.7%) |

|

|

Window period in STEMI |

|||

|

< 3 hours |

181 (23%) |

8 (13.6%) |

|

|

4–6 hour |

173 (22%) |

7 (11.8%) |

|

|

> 6 hours |

433 (55%) |

44 (74.6%) |

0.005 |

|

Coronary angiogram findings |

n = 730 |

n = 61 |

|

|

Recanalized IRA/nonobstructive CAD |

276 (28.3%) |

29 (35.4%) |

NS |

|

Thrombus |

178 (18.1%) |

5 (6.2%) |

0.006 |

|

Obstructive CAD |

246 (25.1%) |

22 (26.1%) |

NS |

|

Normal coronaries |

30 (3.1%) |

6 (7.4%) |

NS |

|

No. of vessels involved |

|||

|

Single vessel |

614 (84.1%) |

52 (85.2%) |

NS |

|

Double vessel |

66 (9%) |

6 (9.8%) |

|

|

Triple vessel |

45 (6.2%) |

3 (4.9%) |

|

|

LMCA |

5 (0.7%) |

0 |

|

|

No. of lesions |

n = 886 |

n = 63 |

|

|

LAD |

670 (75.6%) |

55 (87.3%) |

NS |

|

RCA |

127 (14.3%) |

5 (7.9%) |

|

|

LCX |

84 (9.5%) |

3 (4.8%) |

|

|

LMCA |

59 (0.6%) |

0 |

|

|

Treatment |

|||

|

PTCA |

252 (25.7%) |

17 (21%) |

NS |

|

CABG |

26 (2.7%) |

2 (2.5%) |

|

|

Medical |

702 (71.6%) |

63 (76.5%) |

|

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease; CSA, chronic stable angina; IRA, infarct-related artery; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex; LMCA, left main coronary artery; NS, not significant; NSTEMI, Non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angiography; RCA, right coronary artery; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; UA, unstable angina; WHR, waist-hip ratio.

p < 0.01 is statistically significant.

-

Fig. 1 Risk factor characteristics of young males and females with CAD. BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist-hip ratio.

Fig. 1 Risk factor characteristics of young males and females with CAD. BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist-hip ratio.

Clinical and Angiographic Characteristics

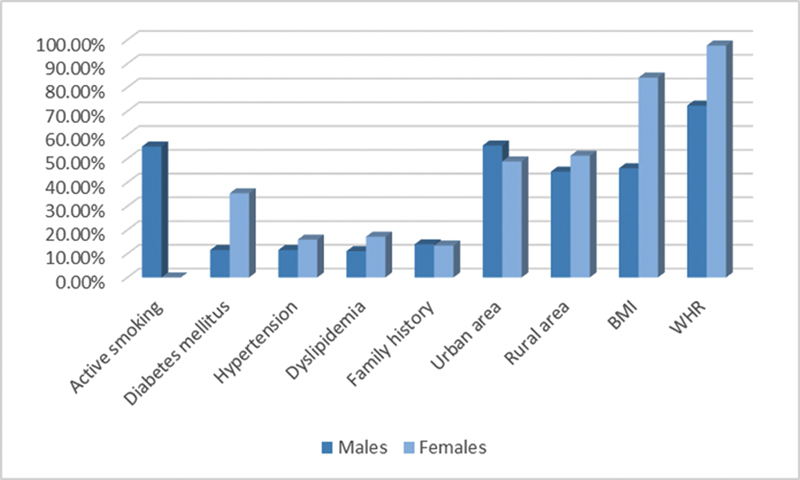

Among females, 71.9% presented with STEMI to hospital, among which 30 were evolved MI and 1 had spontaneous resolution, 20.7% presented with NSTEMI, 3.7% with unstable angina (UA) and 3.7% with exertional angina. In males, 80.4% presented with STEMI to hospital, among which 311 were evolved MI and 19 had spontaneous resolution, 16% presented with NSTEMI, 1.8% with UA and 1.8% with exertional angina (as shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2).

-

Fig. 2 Clinical presentation of ischemic heart disease (IHD) in young males and females with coronary artery disease (CAD). CSA, chronic stable angina; NSTEMI, non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; UA, unstable angina.

Fig. 2 Clinical presentation of ischemic heart disease (IHD) in young males and females with coronary artery disease (CAD). CSA, chronic stable angina; NSTEMI, non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; UA, unstable angina.

Among female STEMI patients, 13.6% had a window period of < 3 hours, 11.8% presented between 4 to 6 hours and 74.6% presented after > 6 hours. Among male STEMI patients, 23% had a window period of < 3 hours, 22% presented between 4 to 6 hours, and 55% presented after > 6 hours. Anterior wall MI (AWMI) was the most common presentation in both sexes (92% in males) and (93% in females). Thrombolysis was done in 94% cases, only 6% underwent primary PCI.

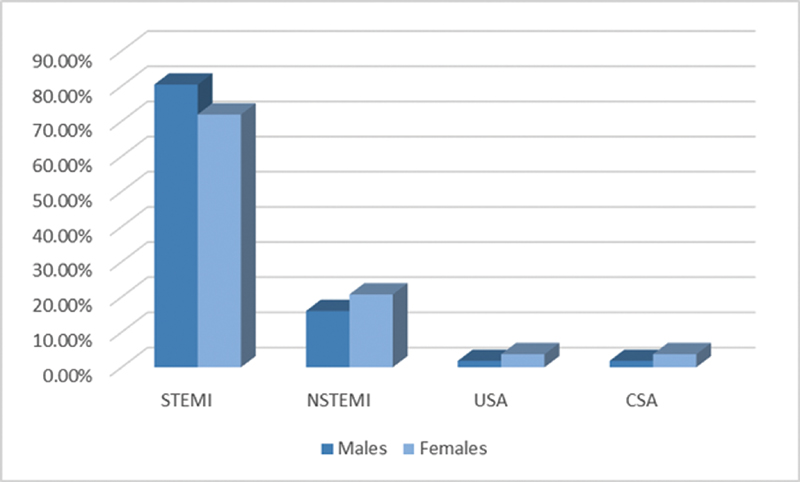

Coronary angiogram was done in 74.1% females, of which 3 females underwent primary PCI, and the rest did not give consent for angiogram. Of them, 35.4% had either recanalized vessels or nonobstructive CAD, 6.2% had thrombus, 3 with nonocclusive thrombus, and 2 with total thrombotic occlusion. Obstructive coronary disease was seen in 26.1% and normal coronaries were seen in 7.4% (as shown in Table 1 and Fig. 3).

-

Fig. 3 Lesion characteristics on coronary artery disease (CAD) in young males and females with CAD. IRA, infarct-related artery.

Fig. 3 Lesion characteristics on coronary artery disease (CAD) in young males and females with CAD. IRA, infarct-related artery.

Coronary angiogram was done in 74.5% males, of which 47 males underwent primary PCI, and the rest did not give consent for angiogram. Of them, 28.3% had either recanalized vessels or nonobstructive CAD, 18.1% had thrombus, 146 with nonocclusive thrombus, and 31 with total thrombotic occlusion. Obstructive coronary disease was seen in 25.1% and normal coronaries were seen in 3.1% (as shown in Table 1 and Fig. 3).

SVD was the most common in both sexes, found in 84.1% males and 85.2% females. Double-vessel disease (DVD) was found in 9% males and 9.8% females. Triple-vessel disease (TVD) was found in 6.2% males and 4.9% females (as shown in Table 1).

Left anterior descending (LAD) artery was the most common artery involved in both sexes, contributing to 670 of 886 lesions, 75.6% in males, and 55 of 63 lesions, 87.3% in females. Right coronary artery (RCA) was involved in 14.3% males and 7.9% females. Left circumflex artery (LCX) involvement was noted in 9.5% males and 4.8% females. LMCA disease accounted for only 0.7% and was seen only in males (as shown in Table 1 and Fig. 4).

-

Fig. 4 The site of lesions in young males and females with CAD. LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex; LMCA, left main coronary artery; RCA, right coronary artery.

Fig. 4 The site of lesions in young males and females with CAD. LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex; LMCA, left main coronary artery; RCA, right coronary artery.

Among females, 21% underwent PCI with stenting. Two patients were referred for CABG and the rest were managed medically. Among males, 25.7% underwent PCI with stenting. As much as 2.7% patients were referred for CABG and the rest were managed medically (as shown in Table 1).

Discussion

CAD is a disease of older population and is uncommon in young, although it occurs at younger age in India compared with the Western population. The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events study noted a prevalence of 6.3% for young ACS; in the Thai ACS registry, it was 5.8% and in the Spain registry, it was 7%.9 10 11 In a study in south Indians by Iragavarapu et al, it was 10.4%.12 In our study, the prevalence of young ACS is 16%.

Demographic and Risk Factor Characteristics

The INTERHEART study revealed that the first presentation of CAD in women is approximately 10 years later than men, most commonly after menopause.13 In our study, we noted that females were younger and premenopausal (mean age 35.4 ± 4.68 years). In the coronary artery disease in the young (CADY) registry, it was noted that the conventional risk factors (like smoking, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia) were high in Indian patients with PCAD and also women had higher prevalence of these risk factors compared with men.14 The INTERHEART study also showed that hypertension and diabetes were more important risk factors in younger Indian women than men.13 Our study also noted a higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia in women. Diabetes in females was statistically significant (p < 0.001). Young women with CAD form an interesting subgroup as the protective effects of estrogen are superseded to cause the disease. Women with diabetes are at greater risk for cardiovascular complications than their male counterparts. In a meta-analysis of 37 prospective cohort studies, the risk of fatal CHD is 50% higher in women with diabetes compared with male diabetics.15

In our study, smoking was found mainly in males. There were no females who smoked in our group. Smoking and low physical activity in Indians have been found to be prevalent in 20- to 39-year-old urban adults by Gupta et al.16

The INTERHEART study also observed that smoking was a greater risk factor in younger men than in women.13 In young males, smoking is considered as a strong risk factor for CAD. According to the Framingham study, repeated exposure to cigarette smoke leads to catecholamine surges that damage the endothelial cells and lead to dysfunction and injury of the vascular intima.17 Other epidemiological studies from India also suggest a greater association of smoking with CAD in younger individuals.18

Another important emerging independent risk factor for CAD in young Indian patients is presence of family history of CAD.19 In our study, we noted that 11females (13.4%) and 136 males (13.9%) had significant family history of CAD. There were no significant gender differences with respect to family history of CAD in our study. Family history of CAD emerged as an important risk factor in young Indian patients in the study by Goel et al.18

WHR and BMI were higher in women (p < 0.001), which can explain the increased prevalence of diabetes in females. Similar findings were noted by Hasan et al where it was noted as an independent risk factor in women with CAD.20

There was no significant difference in the various lipid parameters between the two groups. The HDL levels were found to be low in both, the mean HDL in males was 34.66 ± 11.04, and in females, it was 38.26 ± 22.88. The TGC levels were higher in both sexes. The mean TGC in males was 172.11 ± 107.3, and in females, it was 179.22 ± 125.88. TGC have been found to be a strong risk factor for CAD in women.5 Females with PCAD in our group reflected similar findings. The LDL levels were normal in both. The mean LDL in males was 116.93 ± 86.89, and in females, it was 109.76 ± 54.11.Our findings were similar with those of Pais et al and others who reported high TGC and low HDL cholesterol with normal LDL cholesterol in their cases.21 The lower HDL cholesterol and higher TGC levels were found prominently in young Indians.18 Low levels of HDL cholesterol have been shown to be a powerful risk factor for CAD.18 21

Clinical Characteristics

STEMI was the most common ACS presentation, with majority of patients having SVD, and there was significant delay in first medical contact, especially in females (> 6-hour window period in 74.6% females vs. 55% males). Several studies have shown that women with STEMI have delays in symptom-to-door (STD) and door-to-balloon (DTB) times compared with their male counterparts.22 23 24 AWMI was the most common presentation among both groups.

We noted that females (20.7% vs. 16%) presented more commonly with NSTEMI. Our findings were similar to that noted in the GUSTO IIb, TIMI-IIIB, Euro HEART surveys and CASS study.25 26 27 28 UA and CSA were the least common presentation in both groups.

Angiographic Characteristics

Coronary angiography was performed in both sexes almost equally. Our coronary angiographic data shows predominance of SVD in both young males (84.1%) and females (82%), which is in accordance with Pathak et al, Suresh et al and al-Koubaisy et al.29 30 31 Similar findings were also noted by CASS, Bhardwaj et al and Iragavarapu et al.12 28 32 DVD and TVD was seen almost equally in both groups. However, males showed presence of LMCA disease (0.7%).

Recanalized coronaries/nonobstructive CAD was seen in 35.4% females and 28.3% males, which is concordant with other studies such as Dmoch et al, Sricharan et al, and Noor et al33 34 35 Obstructive CAD was noted in 25.1% males and 26.1% females. Among ACS, the number of recanalized vessels/nonobstructive CAD outnumbered cases of obstructive CAD, indicating predominant thrombus burden, responsive to antithrombotic and/or thrombolytics. Thrombus burden is more in young when compared with elderly as noted by Iragavarapu et al.12 The predominant vessel involved in our young age group is LAD, 76% males and 86% females, which is in concordance with angiographic studies by Iragavarapu et al, Badran et al, Christus et al and Hussein et al.12 36 37 38 TVD was the least common presentation in young patients studied by Jamil et al and Sricharan et al.34 39 Our study also reflected similar findings.

Conclusions

Conventional risk factors such as smoking, abdominal obesity, diabetes, and dyslipidemia (low HDL and high TG) need to be recognized as important risk factors in PCAD patients.

Various awareness programs highlighting the CV risk factors in the young (more so females), with focus on primary prevention are required. Aiming at bridging the knowledge gap of general public and health care workers will ensure early seeking of treatment, prompt diagnosis and urgent referral of all cases. Also, as PCAD patients demonstrate predominantly thrombotic milieu in their coronaries, the role of initial thrombolysis with deferred stenting needs to be explored in them.

Limitations

(1) Passive smoking history in females was not included.

(2) Although many patients complained of stress, we have not used any modality to quantify the degree of stress in our patients.

(3) Intravascular imaging was not done, which could have accurately demonstrated the underlying etiology (atherosclerotic vs. nonatherosclerotic), especially spontaneous coronary artery dissection in young females with normal coronaries or with nonobstructive CAD.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank our Research Coordinator Mrs. Rani B J, and Research Assistant, Mr. Prateesh, for technical help.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Referrals in acute coronary events for cardiac catheterization: The RACE CAR Trial. Can J Cardiol. 2010;8:e290-e296.

- [Google Scholar]

- Heart disease and stroke statistics–2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2006;113(06):e85-e151.

- [Google Scholar]

- How far can risk factors account for excess coronary mortality in South Asians? Can J Cardiol. 1997;13:47B. (Suppl. B):

- [Google Scholar]

- Differences in risk factors, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease between ethnic groups in Canada: The Study of Health Assessment and Risk in Ethnic groups (SHARE) Lancet. 2000;356:279-284. (9226):

- [Google Scholar]

- Plasma triglyceride level is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease independent of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level: a meta-analysis of population-based prospective studies. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1996;3(02):213-219.

- [Google Scholar]

- Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486-2497.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease in women. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(06):617-621.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of age on management and outcome of acute coronary syndrome: observations from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Am Heart J. 2005;149(01):67-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute coronary syndrome in young adults: the Thai ACS Registry. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90:81-90. (1, Suppl 1)

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics and outcome of acute myocardial infarction in young patients. The PRIAMHO II study. Cardiology. 2007;107(04):217-225.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute coronary syndrome in young - a tertiary care centre experience with reference to coronary angiogram. J Pract Cardiovasc Sci. 2019;5(01):18-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937-952. (9438):

- [Google Scholar]

- Premature coronary artery disease in India: coronary artery disease in the young (CADY) registry. Indian Heart J. 2017;69(02):211-216.

- [Google Scholar]

- Excess risk of fatal coronary heart disease associated with diabetes in men and women: meta-analysis of 37 prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2006;332:73-78. (7533):

- [Google Scholar]

- Urban–rural trends in the epidemiology of coronary heart disease. J Assoc Physicians India. 1975;23(12):885-892.

- [Google Scholar]

- Latest perspectives on cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease. The Framingham Study. J Cardiac Rehabil. 1984;4:267-277.

- [Google Scholar]

- A tertiary care hospital-based study of conventional risk factors including lipid profile in proven coronary artery disease. Indian Heart J. 2003;55(03):234-240.

- [Google Scholar]

- Myocardial infarction in young Indian patients: risk factors and coronary arteriographic profile. Am Heart J. 1986;112(01):71-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of metabolic syndrome among young women with premature coronary artery disease. Coron Artery Dis. 2005;16(01):37-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for acute myocardial infarction in Indians: a case-control study. Lancet. 1996;348:358-363. (9024):

- [Google Scholar]

- Sex differences in mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2009;302(08):874-882.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of sex and contact-to-device time on clinical outcomes in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction-findings from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(01):e004521.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gender disparities in first medical contact and delay in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a prospective multicentre Swedish survey study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(05):e020211.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sex, clinical presentation, and outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Coronary Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes IIb Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(04):226-232.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcome and profile of women and men presenting with acute coronary syndromes: a report from TIMI IIIB. TIMI Investigators. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30(01):141-148.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of gender on outcomes of acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(12):1466-1469. , A6

- [Google Scholar]

- Myocardial infarction and mortality in the coronary artery surgery study (CASS) randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 1984;310(12):750-758.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors, angiographic characterization and prognosis in young adults presented with acute coronary syndrome at a tertiary care center in North India. BMR Med. 2016;3:1-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coronary artery disease in young adults: Angiographic study – A single center experience. Heart India. 2016;4:132-135.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cine angiographic findings in young Iraqi men with first acute myocardial infarction. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1990;19(02):87-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Myocardial infarction in young adults-risk factors and pattern of coronary artery involvement. Niger Med J. 2014;55(01):44-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and angiographic characteristics of coronary artery disease in young adults: a single centre study. Kardiol Pol. 2016;74(04):314-321.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of acute myocardial infarction in young adults: Risk factors, presentation and angiographic findings. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6(02):257-260.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics of the coronary arterial lesions in young patients with acute myocardial infarction. Khyber Med Univ J. 2018;10:81-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Age-related alteration of risk profile, inflammatory response, and angiographic findings in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Clin Med Cardiol. 2009;3:15-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coronary artery disease in young versus older adults in Hilla city: Prevalence, clinical characteristics and angiographic profile. Karbala J Med. 2012;5:1328-1333.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coronary artery disease in patients aged 35 or less – A different beast? Heart Views. 2011;12(01):7-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factor assessment of young patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;3(03):170-174.

- [Google Scholar]