Translate this page into:

Peripartum Cardiomyopathy in South Indian Women—Challenges and Outcomes

Cecily Mary Majella Jayaraj, MD, DM Department of Cardiology, Madras Medical College Chennai, Tamil Nadu 600003 India drmajella@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Introduction Peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) continues to be a therapeutic challenge. Actual incidence is not exactly known as routine screening by echocardiogram is not recommended for all pregnant women across various parts of the world.

Aim We, in our study, report the incidence, clinical profile, and prognosis of peripartum cardiomyopathy among South Indian women in a tertiary care hospital.

Materials and Methods All pregnant ladies, referred for cardiac evaluation in the last month of pregnancy and 5 months postpartum, were included in this study. Transthoracic ehocardiography was used for the diagnosis of PPCM. The patients who were diagnosed with PPCM were followed-up clinically and echocardiographically for 1, 3, 6 months and 1 year.

Results Among 5,475 of pregnant women who were screened with transthoracic echocardiogram, 14 patients were diagnosed with PPCM (0.26%). All 14 PPCM patients presented with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV. The incidence of PPCM was high in primigravida in our subgroup. The thrombus burden was high, constituting 42.86% in our subgroup and mortality occurred in three patients.

Conclusion The incidence of PPCM was 0.25% in our subgroup, with high–thrombus burden. Hence, early diagnosis and proper anticoagulation is the need of the hour among appropriate patients along the heart failure management.

Keywords

peripartum cardiomyopathy

thrombus

echocardiography

Introduction

Peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) is the new onset heart failure occurring in the last month of pregnancy or within first 5 months of the postpartum period.1 Initially introduced in 1849, it was not recognized as a separate clinical entity till the early 1930s. Demakis and Rahimtoola2 were the first to define PPCM in 1971. Diagnosis is often delayed since the symptoms closely mimic that of normal pregnancy. Earlier the diagnosis, the better will be the outcome. If clinical heart failure along with echocardiographic evidence of left ventricular systolic dysfunction with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is <45%,3 4 then the condition is designated as pregnancy-associated cardiomyopathy.

We, in our study, report the observations & outcomes of patients with PPCM in a tertiary care hospital in South India.

Aim

The aim of the study was to evaluate the clinical profile and prognosis of PPCM in a tertiary care hospital in South India.

Materials and Methods

Study Design—Observational Study

Patients in the last month of pregnancy and 5 months postpartum, referred for cardiac evaluation from September 1, 2011 to August 31, 2015 were included in this study. The clinical and serial echocardiographic evaluation was conducted and followed-up at 1, 3, and 6 months and 1 year in these patients.

Inclusion Criteria for Diagnosis of PPCM

Patients who present in the last month of pregnancy and 5 months postpartum.

Left ventricular ejection fraction <45%.

No other etiology of heart failure identified.

Exclusion Criteria

Cardiac disease diagnosed before the last month of pregnancy.

Uncontrolled hypertension/toxemia of pregnancy.

Results

Among the total number (5,475) of pregnant women screened, 14 patients were diagnosed with PPCM that constituted 0.26% (Fig. 1). At the time of diagnosis, the mean age of PPCM patients was 25 ± 3 years.

-

Fig. 1 Number of PPCM patients in our study population. PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy.

Fig. 1 Number of PPCM patients in our study population. PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy.

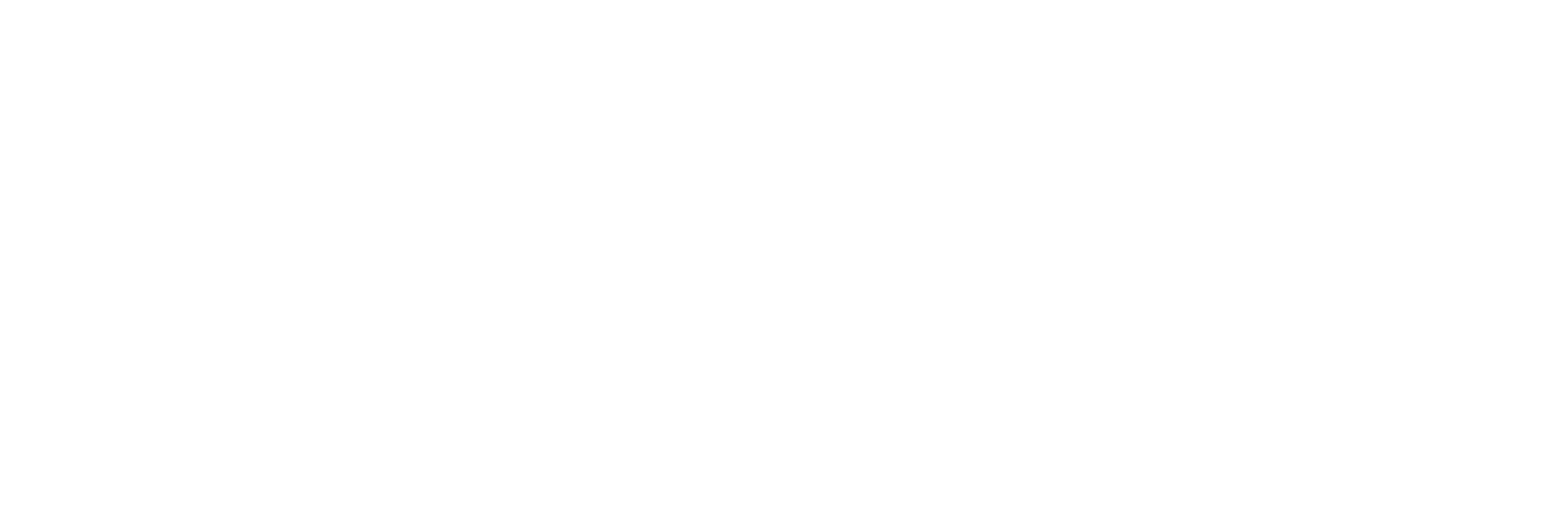

Patients who were diagnosed in the last month of conception were 4 (28%), and those diagnosed in the first month of postpartum were 10 (72%), as represented in Fig. 2.

-

Fig. 2 Time of presentation of PPCM in our subgroup. PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy.

Fig. 2 Time of presentation of PPCM in our subgroup. PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy.

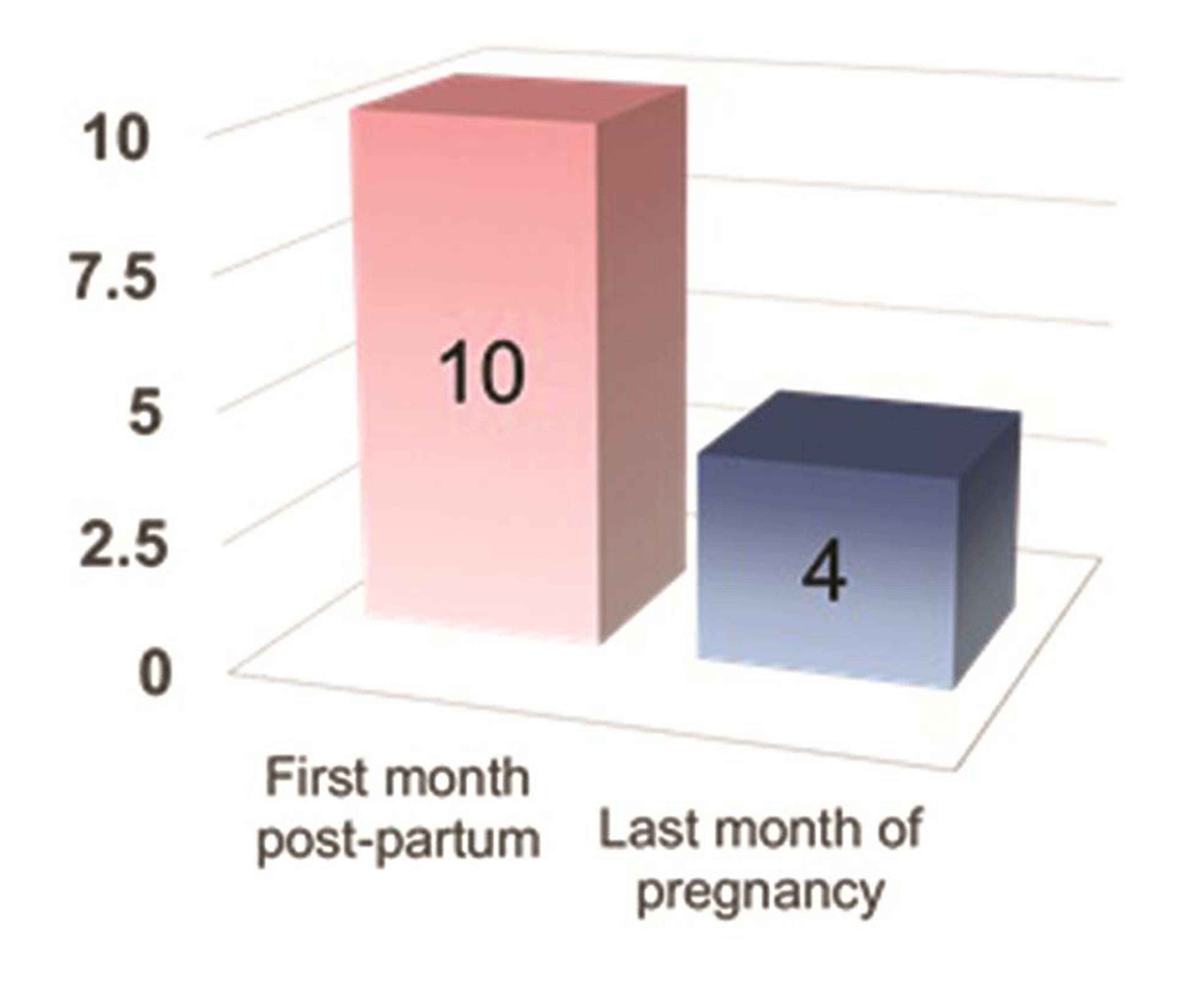

PPCM and parity: as represented in Fig. 3 among PPCM patients, multigravida were 0 (0%), primigravida were 9 (64.3%), and second gravida were 5 (35.7%). The incidence of PPCM was high in primigravida.

-

Fig. 3 Parity and PPCM. PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy.

Fig. 3 Parity and PPCM. PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy.

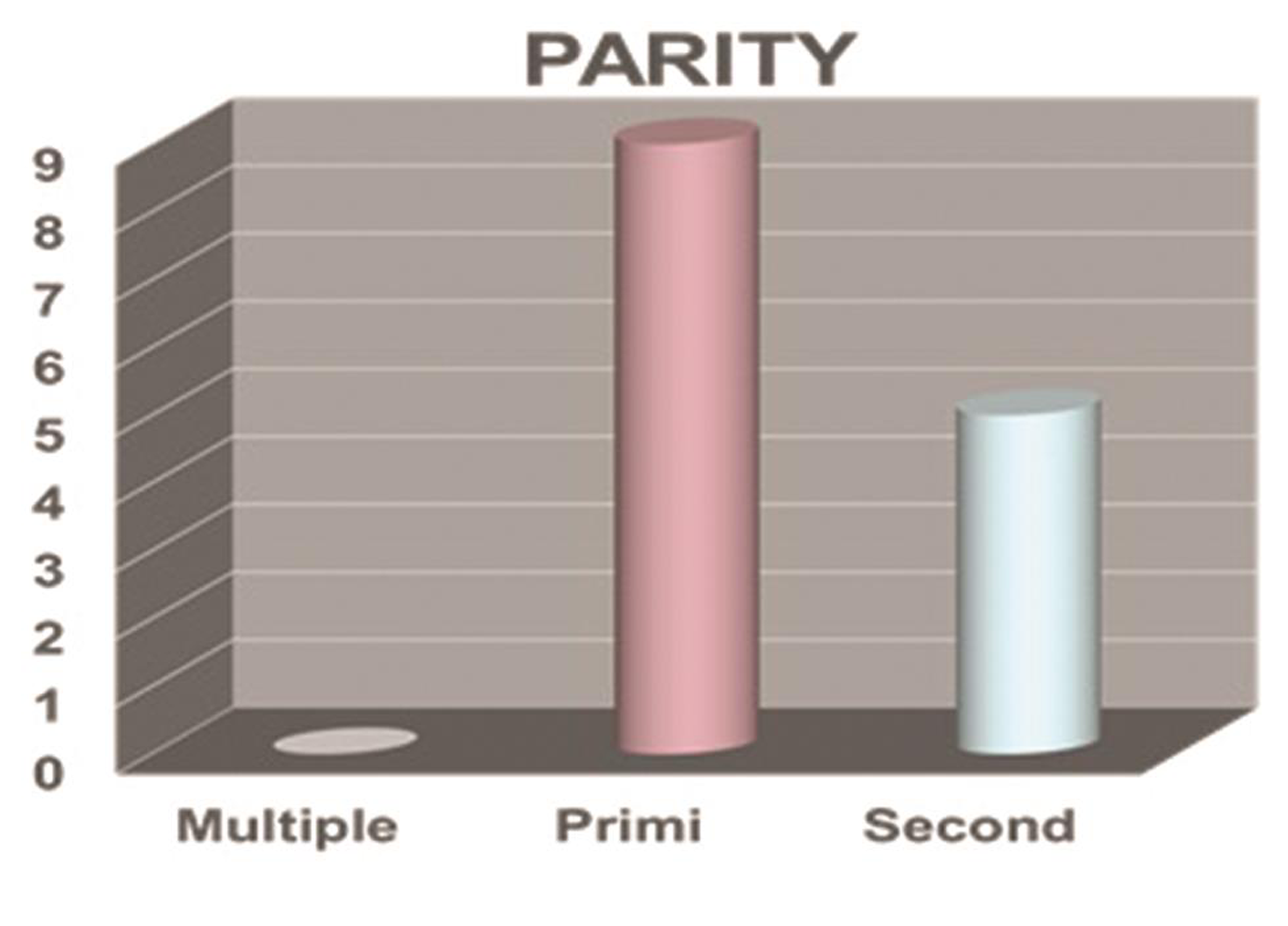

NYHA functional class: patients who presented with NYHA class IV were eight (57.14%), and NYHA class III were six (42.86%), as shown in Fig. 4.

-

Fig. 4 New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class in PPCM. PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy.

Fig. 4 New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class in PPCM. PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy.

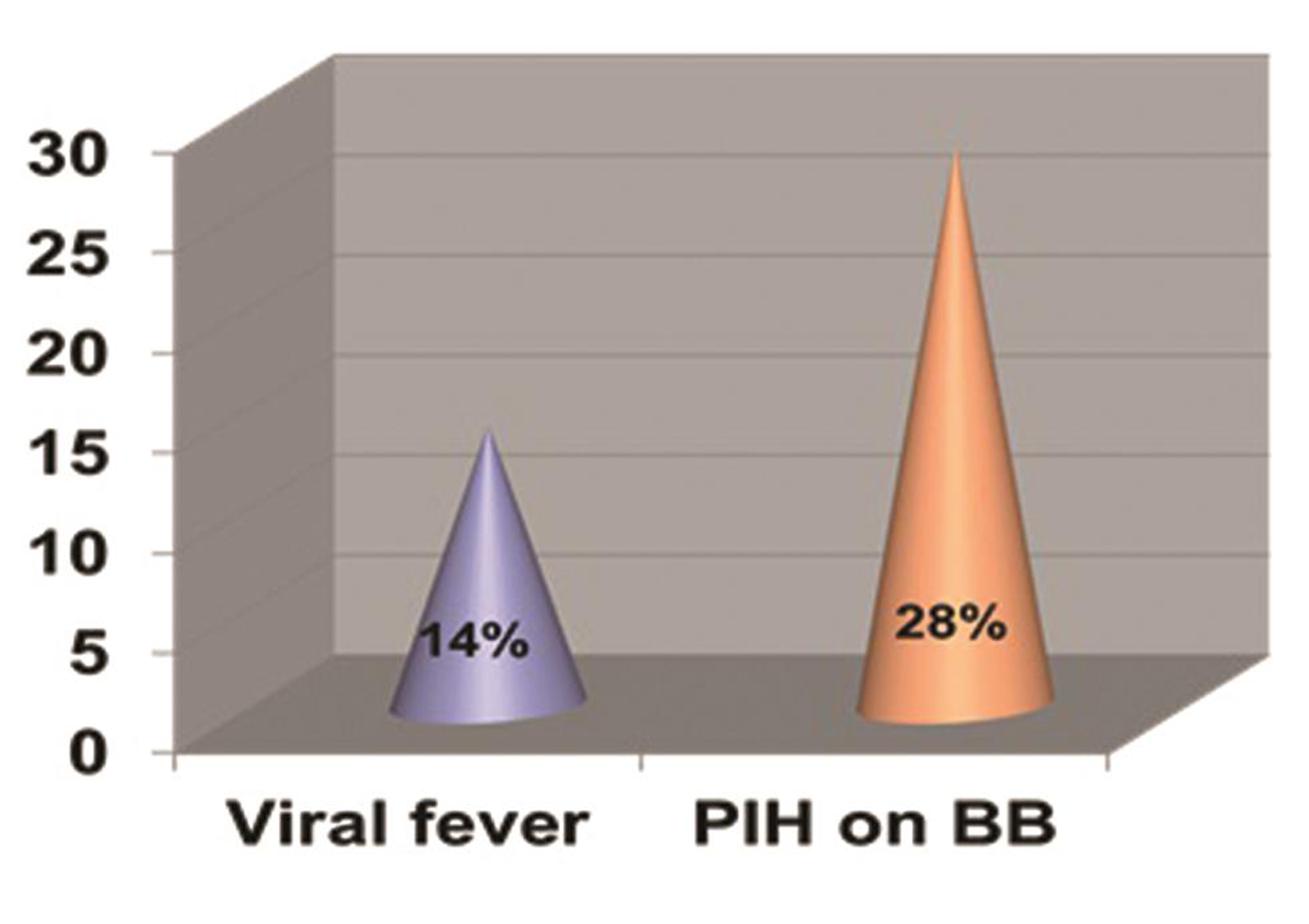

Risk factors: preceding h/o of viral fever was present in two (14.29%) patients, and pregnancy-induced hypertension on treatment with β-blockers for hypertensive control was present in four patients (28.57%), as shown in Fig. 5.

-

Fig. 5 Risk factors in our PPCM subgroup. PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy.

Fig. 5 Risk factors in our PPCM subgroup. PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy.

Echocardiographic Findings

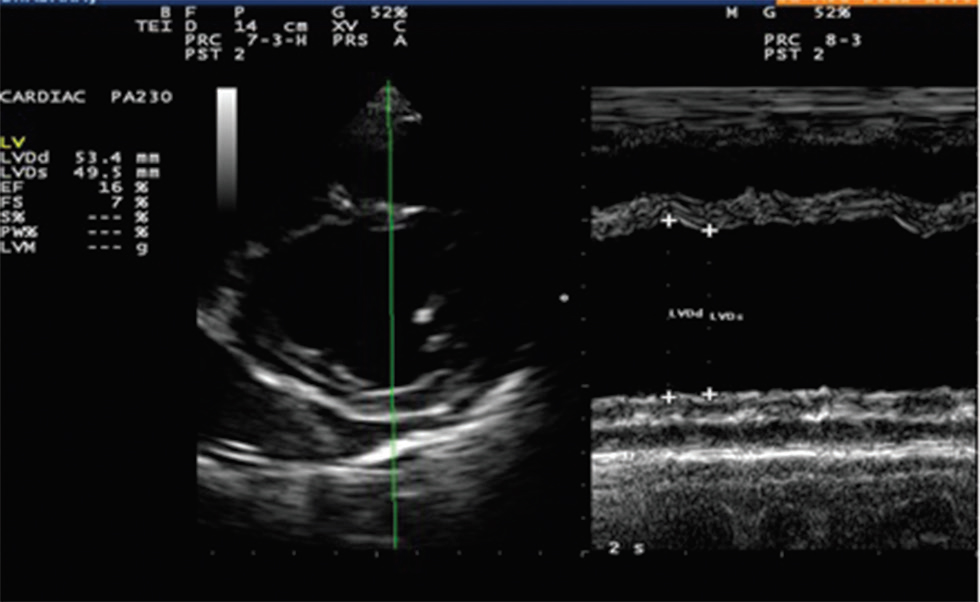

At admission, the findings revealed a mean ejection fraction (EF) of 30 ± 12%, mean fractional shortening (FS) of 22 ± 4%, as shown in Fig. 6 and mean end-diastolic dimension of 5.9 ± 1.8 cm.

-

Fig. 6 ECHO of our patient showing severe LV systolic dysfunction. ECHO, echocardiogram; LV, left ventricle.

Fig. 6 ECHO of our patient showing severe LV systolic dysfunction. ECHO, echocardiogram; LV, left ventricle.

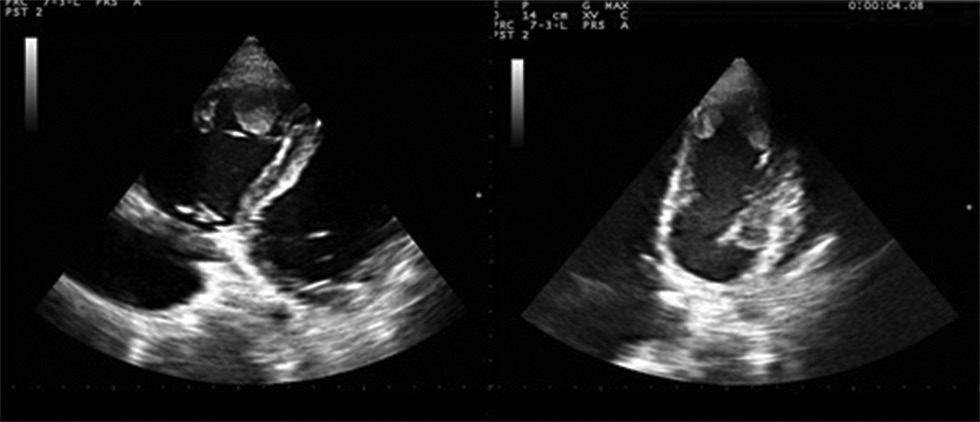

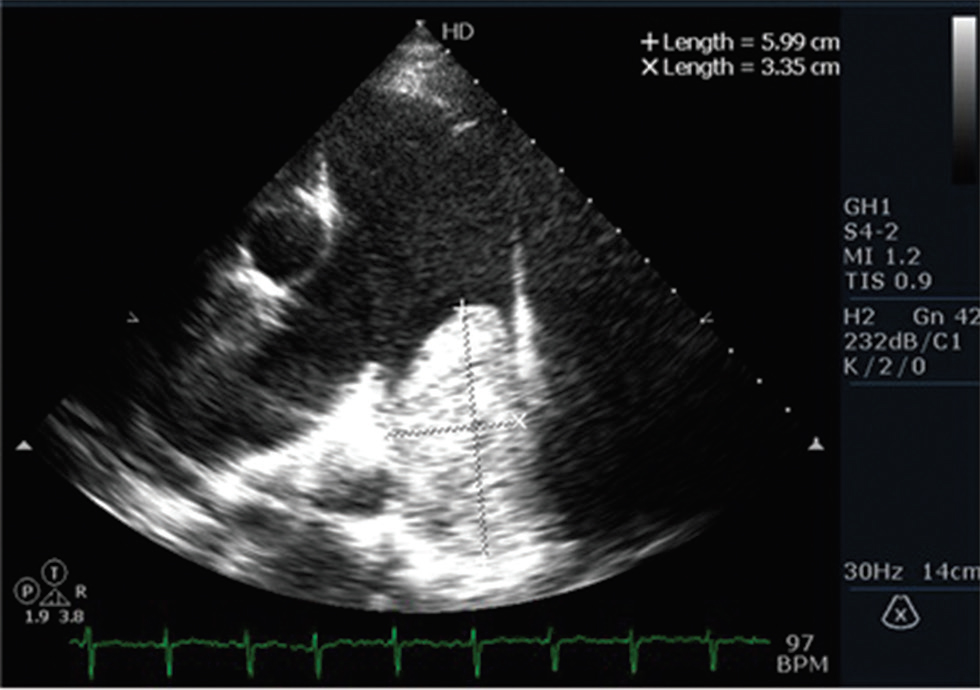

Thrombus: overall thrombus burden was observed in six (42.86%) of the PPCM patients. The distribution of thrombus was as follows: (1) left ventricular thrombus was observed in one patient (7.14%), as shown in Fig. 7; (2) biventricular thrombi were observed in two patients (14.29%), as shown in Fig. 8; and (3) pulmonary embolism in three patients (21.43%; one had saddle type pulmonary embolism, and two had proximal left pulmonary artery embolism), as shown in Fig. 9.

-

Fig. 7 ECHO-A4C: LV apical clot in PPCM. ECHO, echocardiogram; LV, left ventricle; PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy.

Fig. 7 ECHO-A4C: LV apical clot in PPCM. ECHO, echocardiogram; LV, left ventricle; PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy.

-

Fig. 8 ECHO in PPCM showing RV and LV thrombus. ECHO, echocardiogram; LV, left ventricle; PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy; RV, right ventricle.

Fig. 8 ECHO in PPCM showing RV and LV thrombus. ECHO, echocardiogram; LV, left ventricle; PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy; RV, right ventricle.

-

Fig. 9 ECHO–Parasternal Short Axis View (PSAX)view showing left pulmonary artery thrombus. ECHO, echocardiogram.

Fig. 9 ECHO–Parasternal Short Axis View (PSAX)view showing left pulmonary artery thrombus. ECHO, echocardiogram.

Follow-up

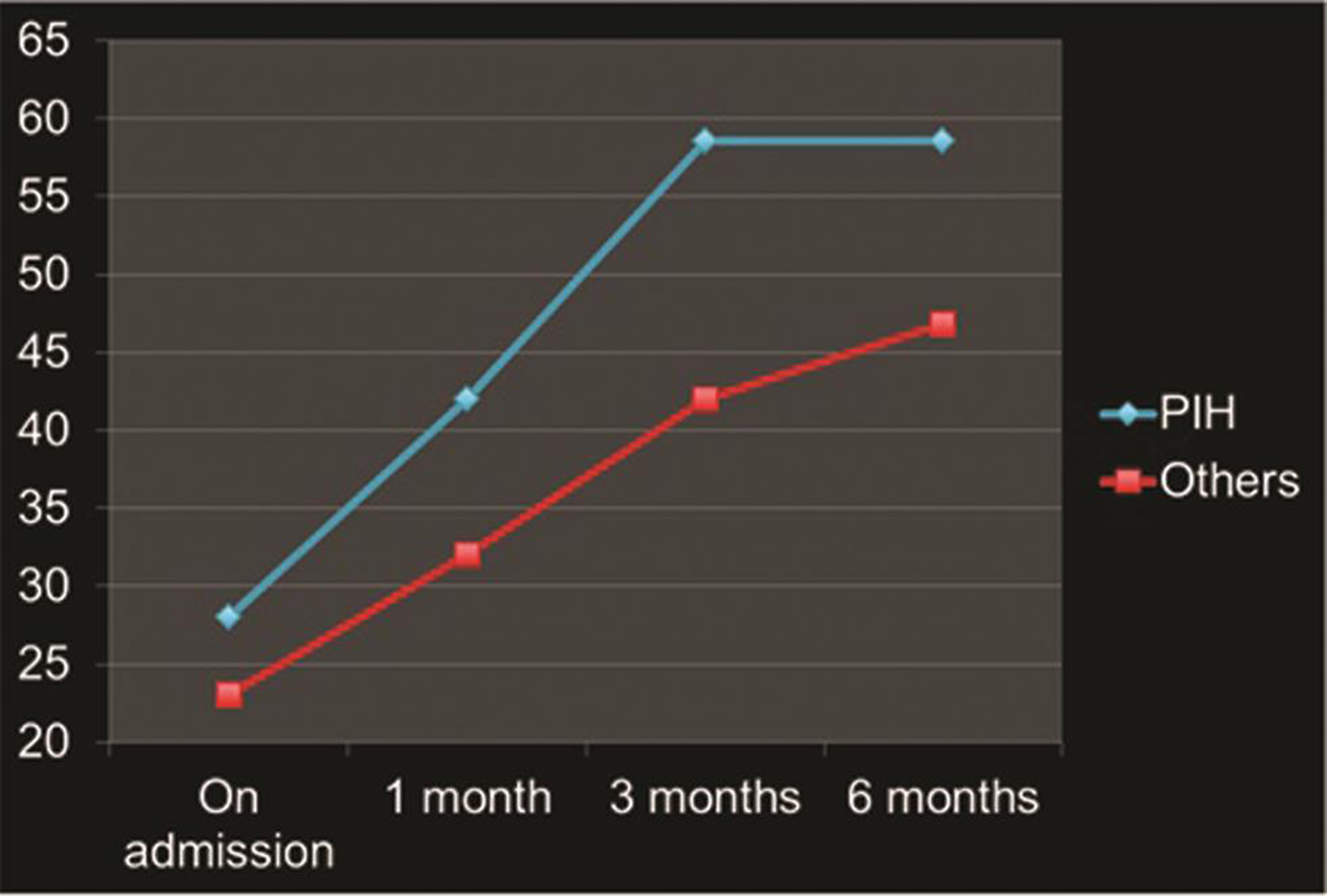

These patients were followed-up for 6 months and 1 year, both clinically and echocardiographically. There was a difference in the recovery patterns of LV dysfunction in PPCM patients with hypertension (PIH) and patients without hypertension. Actually, PIH patients should not be included along with the PPCM patients, but, in this study, the so-called PIH patients were included, as this group of patients did not present with accelerated hypertension at the time of heart failure, and there were no secondary changes like urinary abnormalities or liver function abnormalities. In addition, echocardiogram showed significant LV dysfunction without hypertrophy.

Patients with PIH who were screened periodically by echocardiography were diagnosed earlier and put on β-blockers earlier (3 months vs. 6 months) and complete recovery of ejection fraction (58.6 vs. 46.8%; p = 0.02).

Other predictors of recovery were mean EF (28 vs. 23%; p < 0.001), as shown in Fig. 10 and FS of LV (18 vs. 14%; p = 0.004), and mean EDD (6.1 vs. 5.7 cm; p = 0.08).

-

Fig. 10 Comparison of ejection fraction recovery on follow-up. Foot note: blue line—with hypertension, Red line—without hypertension.

Fig. 10 Comparison of ejection fraction recovery on follow-up. Foot note: blue line—with hypertension, Red line—without hypertension.

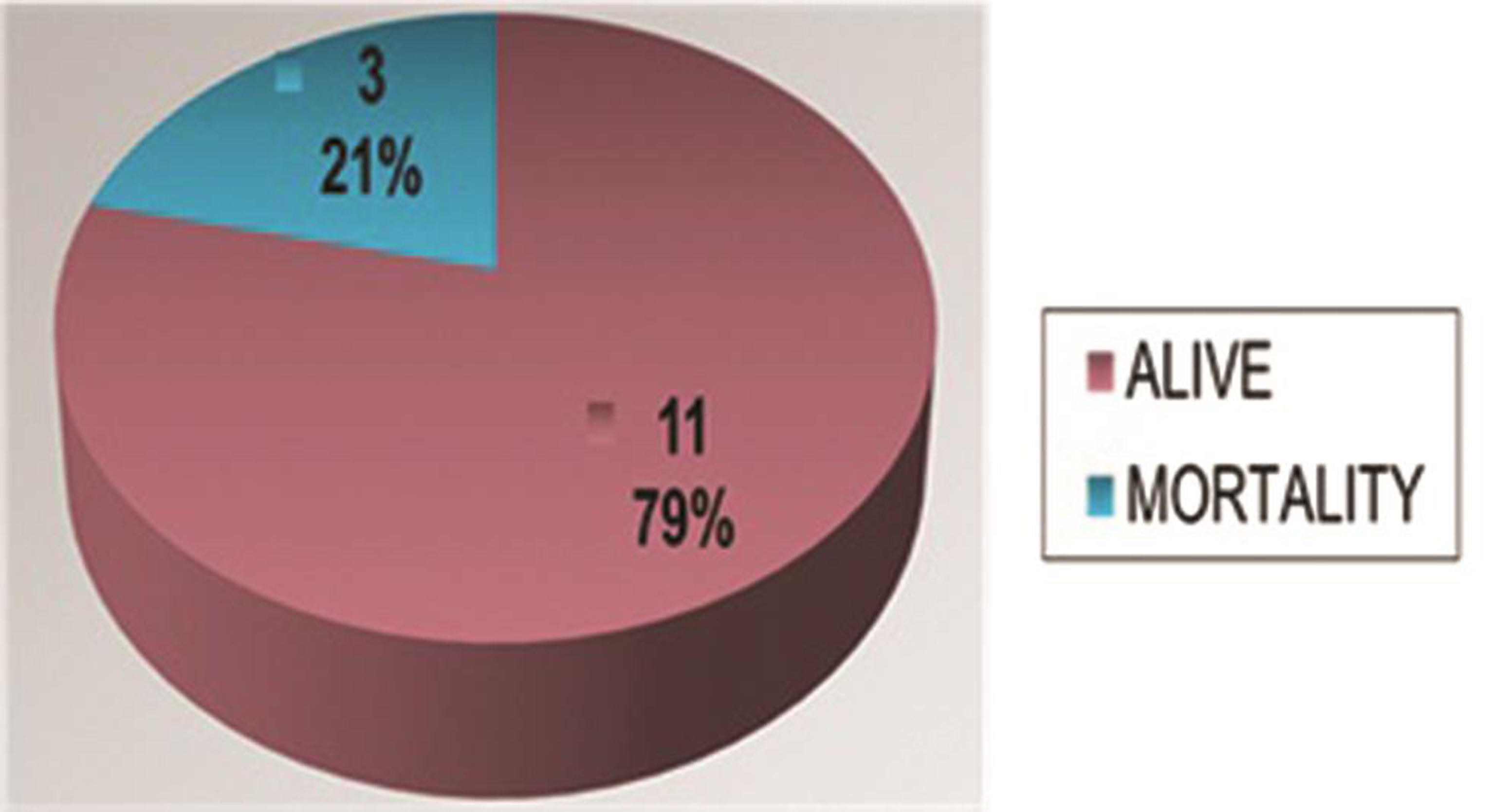

Mortality occurred in three patients (21.43%) in the study population, as shown in Fig. 11.

-

Fig. 11 Mortality in PPCM. PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy.

Fig. 11 Mortality in PPCM. PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy.

Discussion

PPCM is a clinical condition that is still perplexing and portends diagnostic and therapeutic challenges despite improvements in health care systems. Since the symptoms and signs of PPCM often resemble that of normal pregnancy, the diagnosis is often delayed. Since earlier diagnosis, frequent monitoring and early optimization of drug therapy favor a better outcome, it is mandatory that all pregnant mothers should be properly screened, especially when symptomatic.

Echocardiography is an important diagnostic tool that aids in diagnosis and early recognition of complications. The incidence, clinical profile, prognosis, and outcome of PPCM varies among different subgroups and geographic patterns. The mean age of PPCM patients was 25 ± 3years in our subgroup, and the incidence of PPCM was high in primigravida (74%). The incidence of PPCM varies among different countries because the diagnosis is not always consistent; geographical variation, limited access to echocardiography, and head-to-head age-matched comparison with nonpregnant women is not carried out.1 5 The incidence ranges from 1 in 299 live births in Haiti6 to 1 in 2,229 live births in Southern California7 to 1 in 3,000 to 4,000 live births in the United States.1

Thromboembolism (TE) appears to be one of the common complications of PPCM. In the United States and Europe, it accounts for 6.6 and 6.8%, respectively.8

This thrombus can develop in both sides of the cardiac chambers. The possible mechanism is hypercoagulable state during pregnancy, blood stasis due to hypocontractility of the dilated ventricle, and endothelial injury.9 10 The hypercoagulability state of pregnancy takes 6 to 8 weeks of postpartum to come at normal level. The thrombus burden was high in our subgroup (42.86%) that was comparatively very high when compared with other subgroups.

PPCM patients are associated with an increased catecholamine surge which, in turn, raises blood pressure, heart rate, and, consequently, cardiovascular stress. β-blockers act by decreasing heart rate and blood pressure. Over time, β-blockers protect the heart against tachyarrhythmias, and thereby help the heart to recover and normalize cardiac contraction and function. As we have explained in the results, the patients who had hypertension along with severe LV dysfunction, and presented with heart failure, were included in the study. PPCM patients who presented with hypertension showed better outcome in our study. This may be due to β-blockers’ usage, which is useful for hypertension control, as well as heart failure management. In addition these patients had better EF and FS with smaller LV size when compared with PPCM patients without hypertension which were statistically significant.

Limitations of the Study

The study group is small, and long-term follow-up of more than 1 year was not carried out for all patients.

Conclusion

Thrombus burden is high in our subgroup, and proper anticoagulation is the need of the hour among appropriate patients. Frequent review and echocardiographic follow-up are essential to initiate early treatment. Earlier exposure to β-blockers in PPCM may moderate the disease progression and help in the recovery and better outcome of patients.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Peripartum cardiomyopathy: national heart, lung, and blood institute and office of rare diseases (National Institutes of Health) workshop recommendations and review. JAMA. 2000;283(09):1183-1188.

- [Google Scholar]

- A modified definition for peripartum cardiomyopathy and prognosis based on echocardiography. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(02):311-316.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy-associated cardiomyopathy: clinical characteristics and a comparison between early and late presentation. Circulation. 2005;111(16):2050-2055.

- [Google Scholar]

- Five-year prospective study of the incidence and prognosis of peripartum cardiomyopathy at a single institution. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(12):1602-1606.

- [Google Scholar]

- Temporal trends in incidence and outcomes of peripartum cardiomyopathy in the United States: a nationwide population-based study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(03):e001056.

- [Google Scholar]