Translate this page into:

Structural Heart Diseases during Pregnancy: Part 1—Valvular Heart Diseases

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

It is estimated that about 3% pregnancies can have cardiac disease. There is wide variation in the spectrum of heart diseases. Pregnant women in India and other developing countries continue to show high prevalence of rheumatic heart disease (RHD). Pre-conception counseling based on a good echocardiographic evaluation is the most cost-effective method to prevent morbidity and mortality due to valvular heart disease. With advances in medical science, many with valvular heart disease are living to adulthood and undergoing successful pregnancy. Symptoms of a pregnant woman with a valvular disease depend on the altered hemodynamics of the specific valvular lesion in combination with the physiologic changes inherent to the pregnancy itself. A good echocardiographic evaluation of all pregnant women on their first visit to an obstetrician’s office is an effective strategy to prevent morbidity and mortality from valvular heart diseases. In general, the regurgitant lesions are well tolerated during pregnancy and labor. Asymptomatic but significant valve lesions can be decompensated by many factors. Severely stenosed mitral and, sometimes, aortic valve may have to be balloon-dilated by trained experts in midterm taking due care to avoid excess radiation. Valve surgery is rarely performed in absence of any other safer option. A multidisciplinary team approach is required to manage a pregnant woman with significant cardiac lesion with high-risk features and patients having mechanical valves that require continuous anticoagulation.

Keywords

cardiac disease

pregnancy

structural heart diseases

Introduction

Pregnancy and peripartum periods in a woman with heart disease can be a vulnerable phase in the natural history of many valvular heart diseases. With advances in medical science, many with valvular heart disease are living to adulthood and undergoing pregnancy. Symptoms of a pregnant woman with a valvular disease depend on the altered hemodynamics of the specific valvular lesion in combination with the physiologic changes inherent to the pregnancy itself. Either stenosis, regurgitation, or both can occur in one or more of the four major valves. Ventricular function may be preserved or affected to varying degrees that influence the symptoms, treatment, and prognosis. The following review focuses on these problems and their management principles based on recent recommendations of world bodies such as the American Heart Association (AHA), American College of Cardiology (ACC), and European Society of Cardiology (ESC).

Hemodynamics of Normal Pregnancy

Cardiac output (COP) rises by approximately 40 to 50% due to marked increase in stroke volume and a modest rise in heart rate, especially in later weeks of pregnancy. The rise in COP is rapid in the first trimester but plateaus in the second and third trimesters. Simultaneously, because of the hormonal changes of pregnancy, the systemic vascular resistance decreases by end of the second trimester and slowly increases by term. By end of the first trimester, there can be physiologic anemia and expansion of plasma volume. These can lead to an increase in gradients across valves (Table 1). Pregnancy and early postpartum periods are hypercoagulable states that have a potential to affect the functioning of prosthetic valves.

|

Heart rate |

SVR |

COP |

LV size |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: COP, cardiac output; LV, left ventricular; SVR, systemic vascular resistance. |

||||

|

First Trimester |

↑ |

↓ |

↑ |

↑ |

|

Second trimester |

↑ |

↓ |

↑ |

↑ |

|

Third trimester |

↑ |

↓ Late rise |

↑ Late drop |

↑ |

|

Early postpartum |

↓ |

↑ |

↓ |

↓ |

During active uterine contraction, as much as 500 mL blood can be transfused from placental circulation to the maternal systemic circulation. There can be acute rise in COP by 30% during the first stage of labor and approximately 80% in the immediate postpartum stage. This sharp increase is maintained for the first 24 hours of delivery. However, the hemodynamic changes during labor and postpartum periods are also influenced by the type of delivery, use of spinal/epidural anesthetics, and amount of blood loss.

Structural and Functional Changes in Heart in Pregnancy

In an Indian study, the structural and functional changes in maternal heart during pregnancy were studied in 100 patients using standard echocardiographic (echo) methods. With advancing gestational age, there was an increase in left atrial (LA) diameter, left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic diameter, and interventricular septum (IVS) thickness. There was a gradual decrease in E-wave velocity, and E/A ratio increased during the second trimester and decreased during the third trimester. The E-wave deceleration time increased with gestational age. There was no statistically significant difference between IVS thickness and E/A ratio (p = 1.000). These reflect a subtle reduction in myocardial compliance, which could be a normal adaptive response.1

Crux of the Problem

It is estimated that about 3% pregnancies can have cardiac disease. However, there is wide variation in the spectrum of heart diseases. In developed countries, the incidence of rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is on decline, but women in India and other developing countries continue to show high prevalence of RHD, especially in the child-bearing period (Table 2).

|

West (%) |

India (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; RHD, rheumatic heart disease. |

||

|

All CVD |

0.2–4 |

0.5–1 |

|

RHD |

10–15 |

56–89 |

|

Congenital heart disease |

75–82 |

9–19 |

Obstetricians in India are more likely to come across lone mitral stenosis (MS) or along with various degrees of mitral regurgitation (MR). Lone MR (rheumatic or mitral valve prolapse syndrome [MVPS]), lone aortic regurgitation (AR) with or without aortic stenosis (AS), and congenital pulmonary valve stenosis are also not uncommon.3 In the REMEDY (Rationale and design of a Global Rheumatic Heart Disease registry) study conducted in 12 countries in Asia (including India) and Africa that included all pregnant women with cardiac disease, 25% had valvular heart disease. In the same registry, it was observed that heart failure (HF) was present in 22% pregnant women with rheumatic valve disease.4

Mitral Stenosis

Mitral stenosis is invariably rheumatic in etiology and is the most common valve lesion in pregnant women in India. It is common to see that previously asymptomatic cases of moderate to severe MS become symptomatic during pregnancy. With tachycardia, the diastole is shortened, the pressure gradient across the diseased mitral valve increases, and there is increased pulmonary venous and arterial hypertension. Presence of atrial fibrillation accelerates these hemodynamic effects. Thus a pregnant woman with MS becomes increasingly symptomatic as she crosses the middle of the mid-trimester. These abnormalities can lead to maternal and fetal adverse outcomes, including fetal growth retardation, low birth weight, and premature birth. Complications such as pulmonary edema and arrhythmias can occur in 35% of the pregnancies in mothers with severe MS. Premature delivery can vary from 14% (mild MS) to 33% (severe MS).5 At the time of labor and immediately after the delivery due to auto-transfusion of blood, the maternal circulation can be flooded and precipitate pulmonary edema, the risk persisting even up to 24 to 72 hours after delivery. It is at this period the risk for maternal death is the highest.6

Aortic Stenosis

Lone aortic stenosis is more often nonrheumatic in etiology. It is common to have a congenital bicuspid aortic valve that develops valve stenosis and aortopathy or associated coarctation of the aorta (COA). With increasing severity, the maternal and fetal adverse effects increase. Hemodynamic comprise, HF (3–10%), or arrhythmias (25%) can occur maximum in the second and third trimesters or during labor and delivery. The incidence of fetal low birth weight and preterm births are also higher in presence of significant AS (~25%). Maternal mortality can be as high as 17% in presence of severe AS. However, ROPAC (Registry in Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease) was initiated in January 2008 by ESC working group on congenital and valvular heart disease. In this prospective study of 2,966 pregnant women, 96 had at least moderate AS. The mortality in them was zero. However, among symptomatic severe AS, there was increased incidence of HF and hospitalizations. Peak aortic gradient was the most important predictor for worse outcome. Maternal complications rose 2.8-fold and the fetal outcomes increased 7.6 times when the moderate AS became severe in this study.7 8

Pulmonary Valve Stenosis

Typically right-sided stenotic lesions including pulmonary valve stenosis are better tolerated than left-sided stenotic lesions. Very severe pulmonary stenosis (PS) can go into right ventricular failure despite medical treatment. It may be wiser to do balloon valvotomy in select cases.

Regurgitant Lesions

As the systemic vascular resistance (SVR) is decreased in pregnancy, the regurgitant lesions are better tolerated as long as the ventricular function is preserved. The volume overload in the second and third trimesters and acute increase in cardiac output in the first 2 to 3 days after delivery can bring out symptoms such as palpitations and breathlessness in presence of regurgitant lesions. Some patients may have atrial arrhythmias.

Mechanical Heart Valves

A chance to conduct a pre-conception counseling is the best thing in the care of patients with mechanical valves. The need for optimal anticoagulation during pregnancy and delivery must be explained to the patient and her family in detail. In those on high doses of warfarin, embryopathy, hemorrhage, and a fetal loss can occur at a rate of approximately 35%. Warfarin easily crosses the placenta, resulting in significant levels in the fetus. This can result in threatened abortion, typical facial malformations (hypoplastic nose), and stippled epiphyses in more than 6% of children born to mothers treated with warfarin during the first trimester. Neonatal respiratory distress secondary to upper airway obstruction can occur in about one-half of the patients. Exposure during the second and third trimesters seem to have an increased risk of structural anomalies in the central nervous system (such as microcephaly, hydrocephalus, agenesis of corpus callosum, and Dandy-Walker malformation) as well as eye anomalies (optic atrophy, microphthalmia, and Peter anomaly of eye). Other clinical findings of fetal warfarin syndrome (FWS) include scoliosis, significant developmental retardation, deafness, congenital heart disease (CHD), and seizures.9 For those on warfarin in doses > 5 mg/day, recommended dose/drug modification must be performed. In patients with > 5 mg of warfarin, switching to therapeutic doses of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) with low-dose aspirin in the second and third trimesters with periodic monitoring of anti-XA is recommended. The goal is to have 0.8 to 1.2 U/mL after 4 to 6 hours of the last dose.10 11

Arrhythmias

Valvular heart disease can precipitate supraventricular arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation/flutter. Paroxysmal supraventricular arrhythmias can be terminated by vagal maneuvers or adenosine. If ventricular tachycardias occur, they can be reverted using synchronized cardioversion, which is generally safe. Chronic atrial fibrillation, especially with mitral stenosis, calls for chronic anticoagulation as the pregnancy period is more vulnerable for thromboembolic complication. Antiarrhythmic agents such as flecainide or sotalol may be used, if required.

Risk Stratification

A complete history and physical examination along with simple tests such as electrocardiogram (ECG) and two-dimensional (2D) echocardiography can immensely help in assessment of any cardiac disease in pre-conception counseling or the first antenatal checkup. Unfortunately most patients in India and the other developing countries are not aware of cardiac disease. They have cardiac disease for many years until seen and told by the general practitioner or the obstetrician during their first antenatal visit. When symptoms such as progressive dyspnea, orthopnea, nocturnal cough, hemoptysis, syncope, or chest pain are reported, suspect the possibility of cardiac disease. It is important to realize that there can be mistaken overdiagnosis of cardiac disease in pregnancy on clinical examination alone. The first heart sound can be loud because of increase in COP. It can be mistaken as S4 or as a systolic click. Loud P2 may be heard without pulmonary hypertension or an atrial septal defect. Physiologic third heart sound can be present due to increased blood volume, and systolic murmurs due to increased blood flow at the apex or left sternal border may also be appreciated. There can be mammary soufflé that can be mistaken for an organic murmur.12 Presence of marked edema, a fourth heart sound, diastolic murmurs, jugular venous pressure of 2 cm, and a persistent tachycardia of 100 beats/min should alert to the possibility of significant cardiac lesion.13

In pre-conception counseling, the patient and her family must be educated about the nature of the cardiac disease, possible complications, and available options to prevent the same. If the patient has no choice but to undergo a valve surgery, the cardiologist must explain about the relative merits and demerits of mechanical and bioprosthetic valves. The tissue valves are less thrombogenic and do not need anticoagulation if in sinus rhythm, but there is chance for degeneration in approximately 8 years requiring a redo-surgery. Pregnancy is best avoided in presence of severe pulmonary hypertension/Eisenmenger’s syndrome, ventricular ejection fraction < 30%, ventricular dysfunction with New York Heart Association (NYHA) III/IV symptoms, critical MS, symptomatic severe AS, Marfan’s syndrome with ascending aortic diameter > 45 mm, bicuspid aortic valve with aortic diameter > 50 mm, native severe coronary artery disease (CAD), or prior postpartum cardiomyopathy with residual ventricular dysfunction.

There are three well-known risk scores available for stratifying pregnant women with a cardiac lesion (Tables 3 4 5). Currently CARPREG (Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy) score is used widely, especially in presence of valvular heart disease. The ZAHARA (Zwangerschap bij vrouwen met een Aangeboren HARtAfwijking) score is best used when there is a congenital heart disease. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification is more elaborate and broad-based comprising almost all cardiac disorders that can be encountered in pregnancy

|

Group |

Mortality risk (%) |

Lesions |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; ASD, atrial septal defect; ASOG, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; MI, myocardial infarction; MS, mitral stenosis; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; VSD, ventricular septal defect; cardiovascular disease; RHD, rheumatic heart disease. |

|||

|

1 |

1–2 (Minimal) |

ASD, VSD, PDA, pulmonary stenosis, tricuspid stenosis, Corrected TOF, bioprosthetic mitral valve stenosis (class I/II) |

|

|

2 |

5–15 (Moderate) |

||

|

A |

MS II/IV, aortic stenosis, coarctation of aorta without valve affection, uncorrected TOF, previous MI, Marfan’s syndrome with normal aorta |

||

|

B |

Mitral stenosis with AF Artificial valve |

||

|

3 |

25–50 (Major) |

Pulmonary hypertension, coarctation of aorta with valve affection Marfan’s syndrome with aortic involvement |

|

|

Risk factor |

Score and risk of complications |

|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: CARPREG, Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy; EF, ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association. |

|

|

1.Prior cardiac event/arrhythmia 2. NYHA > II or cyanosis 3. Left heart obstruction 4. Systemic ventricular dysfunction (EF < 40%) |

0 = 5% risk 1 = 27% risk > 2 = 75% risk |

|

WHO class |

Conditions included |

|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: AS, aortic stenosis; ASD, atrial septal defect; CHD, congenital heart disease; COA, coarctation of aorta; EF, ejection fraction; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MS, mitral stenosis; MVP, mitral valve prolapse; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PS, pulmonary stenosis; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; VSD, ventricular septal defect; WHO, World Health Organization. |

|

|

I—Risk is like general population |

Mild PS, MVP, PDA, repaired ASD/VSD/PDA, anomalous veins, isolated atrial/ventricular ectopics |

|

II—Small increased maternal mortality and morbidity |

Unrepaired ASD/VSD; repaired TOF; most arrhythmogenic disorders |

|

II/III |

LVEF > 30% but < 50%, NYHA I/II HCM, nonsevere valve stenosis, tissue valve, repaired COA, Marfan’s syndrome without aortic dilatation; bicuspid aortic valve with aorta < 45 mm |

|

III—Significant increased risk |

Mechanical valve, systemic RV, Fontan circulation, unrepaired cyanotic heart disease and other complex CHD, Marfan’s syndrome with aorta 40–45 mm, bicuspid aortic valve with aorta > 45–50 mm |

|

IV—Pregnancy is contraindicated. If not terminated, extreme care required |

Pulmonary hypertension, ventricular EF < 30%—NYHA II–IV, severe AS or MS, previous peripartum cardiomyopathy with residual LV impairment, Marfan’s syndrome with aorta > 45 mm, bicuspid aortic valve with aorta > 50 mm, severe COA |

Modified WHO system for risk assessment of cardiac conditions in pregnancy: This classification has been validated and accepted by ESC guidelines.15

Medical Management

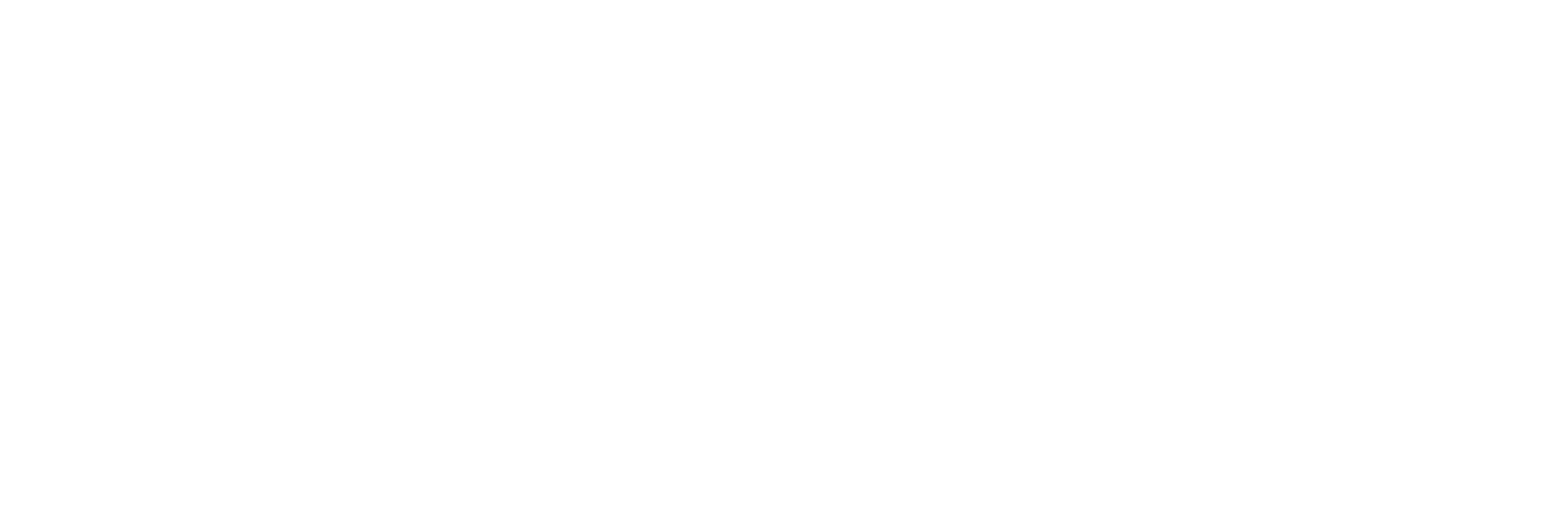

A good echo evaluation of all pregnant women on their first visit to an obstetrician’s office is the most effective strategy to prevent morbidity and mortality from valvular heart diseases. If a significant lesion is found in echo examination in each trimester, the last one at around 32 weeks of gestation is desirable. Echo should include measurement of aortic diameter if bicuspid aortic valve or coarctation is present. If a mechanical valve is present, it requires careful assessment (Fig. 1).

-

Fig. 1 Recommended echo measurements of aortic root and ascending aorta for bicuspid aortic valve: 1, aortic annulus; 2, root diameter; 3, sinotubular junction diameter; 4, ascending aorta diameter. AO, aorta; LA, left atrial; LV, left ventricular.

Fig. 1 Recommended echo measurements of aortic root and ascending aorta for bicuspid aortic valve: 1, aortic annulus; 2, root diameter; 3, sinotubular junction diameter; 4, ascending aorta diameter. AO, aorta; LA, left atrial; LV, left ventricular.

In general, regurgitant lesions are well tolerated during pregnancy and labor. Asymptomatic but significant valve lesions can decompensate by factors such as excess salt ingestion, undue exertion, anemia, hyperthyroidism, infections, systemic hypertension, or arrhythmias. Such precipitating factors have to be prevented if feasible or corrected in time if detected. The management includes anemia correction, heart rate control, and mild diuresis. Metoprolol, diltiazem, or propranolol are widely used agents for this end. Appropriate infective endocarditis prophylaxis is to be done. The drugs that can cause potential harm to the fetus during pregnancy have to be remembered by all physicians while treating patients with valvular disease (Table 6).

|

Drug |

Possible effects |

|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin–converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction. |

|

|

ACE inhibitors/ARB |

Renal/tubular dysplasia, IUGR, growth retardation, ossification defects, lung hypoplasia, contractures, anemia |

|

Warfarin |

Hemorrhage, embryopathy, fetal loss |

|

Statins |

Congenital anomalies |

|

Spironolactone |

Antiandrogenic; cleft abnormalities |

|

Hydralazine |

Fetal tachycardia |

|

Diltiazem |

? teratogenic |

|

Furosemide |

Oligohydramnios |

Infective endocarditis is fortunately a rare complication with a reported incidence of 0.006%, but it has a very high maternal mortality (33%) either due to HF or embolic event. Fetotoxic effects of antibiotics should be understood by all obstetricians and cardiologists. While antibiotics such as penicillin, ampicillin, amoxicillin, erythromycin, mezlocillin, and cephalosporins can be used at all trimesters, aminoglycosides, quinolones, and tetracyclines should be used only for vital indications. Adverse fetal risk cannot be excluded with vancomycin, imipenem, rifampicin, and teicoplanin.16

During labor, obstetricians should try to shorten the second stage and monitor the vitals closely. Avoid methyl ergotamine. Early use of effective epidural anesthesia is recommended for smooth labor. In high-risk cases, elective cesarean section (CS) will help in prevention of acute HF.

An invasive hemodynamic monitoring during labor should be considered in conditions such as unexplained or refractory pulmonary edema, HF or oliguria, intraoperative or intrapartum cardiovascular decompensation, critical AS (< 1 cm2), or MS (< 1.5 cm2), Eisenmenger’s syndrome, NYHA class III or IV cardiac disease, peripartum or perioperative CAD, refractory pulmonary edema, or oliguria in the setting of severe pulmonary hypertension.

Anticoagulation Management in a Patient with Mechanical Prosthetic Valve

In patients having mechanical valves that require continuous anticoagulation, expert team-based management throughout the pregnancy is recommended. Compared with unfractionated heparins (UFHs) or LMWHs, valve thrombosis is lesser with warfarin. In most centers in India, it had been the standard practice to use UFHs before 12 weeks and after 36 weeks of gestation, while using warfarin in between to allow ease of administration at home. Some physicians prefer to substitute warfarin from 6th to 12th week when it is most risky for embryopathy. While a patient is on warfarin, it is unsafe for vaginal delivery. It is advisable to shift from warfarin to LMWFs at 36 weeks of gestation. CS is to be offered if a woman goes into labor while on warfarin after administration of vitamin K 10 mg intravenously over 20 to 60 minutes and sometimes there may be a need for use of fresh frozen plasma. Some centers monitor peak or trough levels of factor Xa to monitor the levels of enoxaparin. LMWHs have to be stopped 24 hours before induction of labor. Resumption of UFH can be at approximately 6 hours after vaginal delivery or 12 hours after CS. Warfarin can be resumed as soon as possible after delivery.17 18 19

Cardiac Indications for Cesarean Section Delivery

Patients with mild or moderate to severe MS without pulmonary hypertension can be allowed to try vaginal delivery, but in presence of pulmonary hypertension or symptoms in class III or IV, CS is safer. In conditions such as dilated aortic root > 4 cm in COA, severe AS, acute severe HF, and history of recent myocardial infarction (MI), use of warfarin within the past 2 weeks and a need for emergency valve replacement immediately after delivery call for an elective CS.

Role of Percutaneous Methods

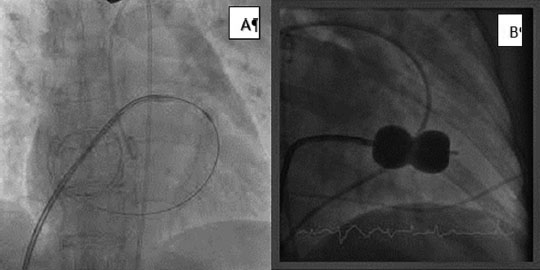

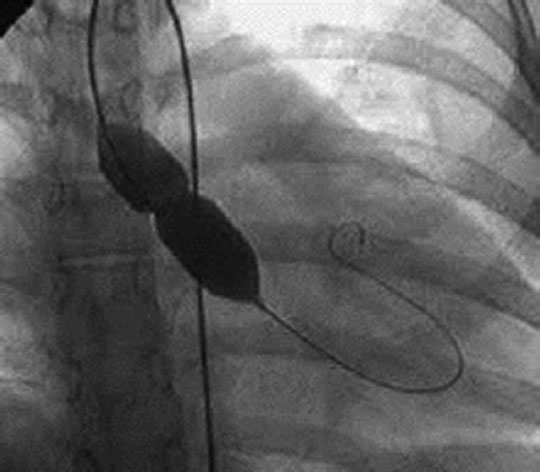

Severe MS is poorly tolerated, and if the valve is suitable, percutaneous mitral valvotomy (PMV) is to be strongly considered. As exposure to radiation is an important concern. Proper assessment of valve morphology, performance by an expert with experience, adequate shielding of the mother’s abdomen with lead sheet during the procedure (Figs. 2, 3A, B and 4), and performing most of the steps involved without use of fluoroscopy will be desirable. When planned electively, 20th to 24th week is the best time for its performance as the organogenesis is complete and fetal thyroid is still inactive. Most of the popular cardiac centers in India with large volume of interventions can perform successful percutaneous balloon mitral valvotomy (PBMV) with least fluoroscopy time. At NIMS, Hyderabad, during 2009 to 2014, 50 PMV cases were done in pregnant women with 100% success rate. There were no complications or deaths. The mean fluoroscopic time was 4 minutes (unpublished data). Aortic and pulmonary valvoplasties are rarely performed unless the lesions are severe, and the patient is symptomatic. They are not done as routine prophylactic measures.20 21 22 23 24

-

Fig. 2 Our practice of abdominal protection with lead aprons during percutaneous balloon mitral valvotomy in a pregnant woman.

Fig. 2 Our practice of abdominal protection with lead aprons during percutaneous balloon mitral valvotomy in a pregnant woman.

-

Fig. 3 (A, B) Images during percutaneous balloon mitral valvotomy in one of our cases.

Fig. 3 (A, B) Images during percutaneous balloon mitral valvotomy in one of our cases.

-

Fig. 4 Image during percutaneous balloon aortic valvotomy in one of our cases.

Fig. 4 Image during percutaneous balloon aortic valvotomy in one of our cases.

Surgical Procedures

Surgery during pregnancy is a team decision to be taken after much deliberation about the benefit and risk to the mother and fetus. With advances in anesthesia and surgical practice, the maternal mortality during cardiopulmonary bypass is now like that in nonpregnant women (9%), but fetal mortality remains high, that is, 30 to 40%. There is significant morbidity including late neurologic impairment in 3 to 6% of children. The best period for surgery is between the 13th and 28th week. If gestational age is 28 weeks or more, delivery before surgery is considered. Cardiopulmonary bypass time is minimized. MVR is reserved when PBMV cannot be performed, however, at an expense of 1.5 to 5% maternal mortality and fetal loss of approximately 16 to 33%.25

In the recently held ESC conference at Munich, the management of pregnancy with heart disease was discussed at length and their recommendations were published. The highlights are depicted in the Table 7. In high-risk patients, management by “pregnancy heart team” is highly recommended in these guidelines.26

|

Abbreviations: AR, aortic regurgitation; AS, aortic stenosis; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; LA, left atrial; LV, left ventricular; MR, mitral regurgitation; MS, mitral stenosis; MVA, mitral valve area; VKA, vitamin K antagonist. |

|

1. The pregnancy heart team consisting of multidisciplinary experts is to be created in all major hospitals for managing high–risk patients |

|

2. Vaginal delivery is to be encouraged in most cases as far as feasible |

|

3. Prophylactic antibiotics to prevent endocarditis is no longer recommended |

|

4. In MS with MVA < 1 cm2 intervention is recommended before pregnancy |

|

5. In MS if atrial fibrillation/LA thrombus or prior history of embolism, heparins or VKA recommended |

|

6. In AS, intervene before pregnancy if LV dysfunction or symptoms are present; if detected while pregnant, do exercise testing if no symptoms are reported |

|

7. For severe AR/MR, surgery is recommended before pregnancy if symptoms are present/LV dilated/dysfunctional |

|

8. If pregnant with a mechanical valve, the heart team should be consulted |

Conclusion

Pre-conception counseling based on a good echo evaluation is a very cost-effective method to prevent morbidity and mortality due to valvular heart disease during pregnancy and deliver. There is a need for a multidisciplinary team approach to manage a pregnant woman with significant cardiac lesion with high-risk features.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Structural and functional changes in maternal heart during pregnancy: an echocardiographic study. Indian J Cardiovasc Dis Women. 2017;2:72-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy complicated by valvular heart disease: an update. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(03):e000712.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rationale and design of a Global Rheumatic Heart Disease registry: the REMEDY study. Am Heart J. 2012;163(04):535.e1-540.e1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac risk in pregnant women with rheumatic mitral stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(11):1382-1385.

- [Google Scholar]

- Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. (10th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2015.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early and intermediate-term outcomes of pregnancy with congenital aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(11):1386-1389.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk of pregnancy in moderate and severe aortic stenosis: from the multinational ROPAC registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(16):1727-1737.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risks of anticoagulant therapy in pregnant women with artificial heart valves. N Engl J Med. 1986;315(22):1390-1393.

- [Google Scholar]

- A prospective trial showing the safety of adjusted-dose enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis of pregnant women with mechanical prosthetic heart valves. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2011;17(04):313-319.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(22):2438-2488.

- [Google Scholar]

- Textbook of Obstetric Medicine—Management of Medical Disorders in Pregnancy. (6th ed). New Delhi, India: Jaypee Brothers; 2015. 131–153

- [Google Scholar]

- Heart disease in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;29(05):579-597.

- [Google Scholar]

- ACOG technical bulletin number 168—June 1992. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1993;41(03):298-306.

- [Google Scholar]

- ESC guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(24):3147-3197.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bacterial endocarditis. A serious pregnancy complication. J Reprod Med. 1988;33(07):671-674.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy with prosthetic heart valves—30 years’ nationwide experience in Denmark. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40(02):448-454.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy in women with a mechanical heart valve: data of the European Society of Cardiology Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC) Circulation. 2015;132(02):132-142.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anticoagulation during pregnancy: evolving strategies with a focus on mechanical valves. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(16):1804-1813.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous balloon mitral commissurotomy during pregnancy. Heart. 1997;77(06):564-567.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous balloon mitral valvotomy during pregnancy. Pak J Biol Sci. 2013;16(04):198-200.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty in comparison with open mitral valve commissurotomy for mitral stenosis during pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(03):900-903.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty during pregnancy. Int J Cardiol. 1991;32(01):1-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pulmonary valvuloplasty in a pregnant woman using sole transthoracic echo guidance: technical considerations. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31(01):103.e5-103.e7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiopulmonary bypass and mitral valve replacement during pregnancy. Perfusion. 2005;20(06):359-368. [PubMed: 16363322]

- [Google Scholar]

- 2018 ESC guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(34):3165-3241.

- [Google Scholar]