Translate this page into:

Pregnancy in Congenital Heart Diseases

Shweta Bakhru, DNB (Ped), FNB (Ped Cardiology), Pediatric Cardiologist Care Hospital, Banjara Hills, Hyderabad 500034, Telangana India hrehaan2015@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Congenital heart diseases (CHDs) affect 0.8 to 1.5% of general population. With increase in awareness and medical services, more number of patients with CHDs have entered into adulthood. One of the peculiar physiologic changes in women is going through pregnancy. Misconceptions are common in women with CHD. This write-up is to provide some brief information about CHD patients going through pregnancy. General cardiovascular risk and individual disease-related risks are discussed.

Keywords

cardiovascular risk

congenital heart disease

pregnancy

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is one of the most common birth defects.1– 4 It affects 0.8 to 1.5% of the general population.5– 7 With increase in awareness and medical services, more number of patients with CHDs have entered into adulthood. One of the physiologic changes in women is going through pregnancy. Misconceptions are common in CHD women. Structured, preconception evaluation and appropriate management are essential to avoid morbidity and mortality. This write-up is an attempt to provide brief information about CHD patients going through pregnancy.

Physiologic Implication of Pregnancy on Cardiovascular System

During pregnancy, to accommodate increase in blood volume, changes in cardiac output, heart rate, and systemic and pulmonary vascular resistance occur. These changes vary during antenatal, natal, and postnatal periods. Usually these hemodynamic burdens are well tolerated in women without CHD.

-

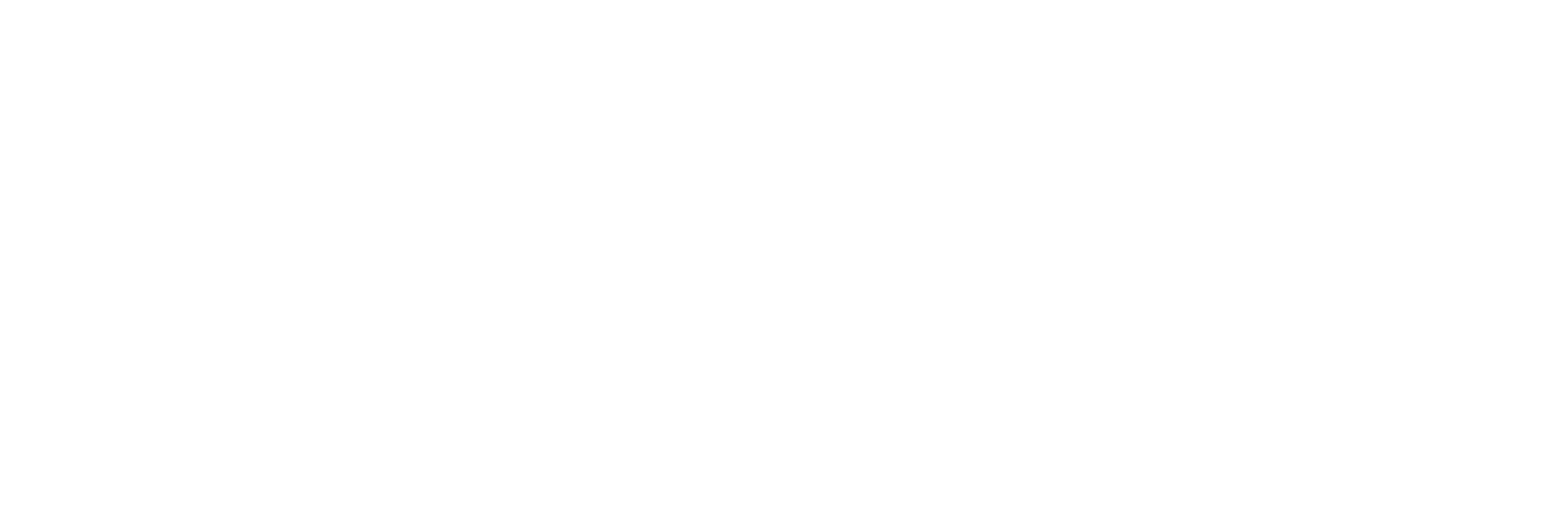

Fig. 1 Multidirectional approach to pregnant woman with CHD. GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension.

Fig. 1 Multidirectional approach to pregnant woman with CHD. GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension.

Hemodynamic changes during pregnancy and postpartum period are studied by Robson et al.8– 13 There is increase in stroke volume, heart rate, and cardiac output as early as fifth week of gestational age. It persistently increases throughout pregnancy,8 13 whereas systemic vascular resistance starts dropping from fifth week of gestational age till the end of the second trimester. It starts incrementing from 32 weeks onward till term and can reach beyond prepregnancy state.8 9 12– 14 Treating physician must have adequate knowledge of these changes while encountering CHD women. Physiologic changes impose burden on cardiovascular system in a compromised heart.

Risk Assessment and Stratification for Adverse Maternal and Fetal Complication

In general, the risk factors listed in Tables 1 and 2 are considered to be potential for adverse maternal and neonatal complications.19

|

Abbreviations: EF, ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion. |

|

1. Poor functional class (NYHA class 3 or 4) or cyanosis 2. Systemic ventricle EF < 40% 3. Mitral valve area < 2 cm2, aortic valve area < 1.5 cm2 or peak left ventricular outflow tract gradient > 30 mm Hg (moderate to severe) 4. Prepregnancy cardiac event (symptomatic arrhythmia, stroke, pulmonary edema) 5. Subpulmonic ventricular dysfunction (TAPSE < 16) 6. Moderate to severe pulmonary regurgitation 7. Mechanical heart valves 8. Moderate to severe atrioventricular valve regurgitation 9. Cyanosis (saturation < 90%) 10. Natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP > 128 pg/mL at 20 wk is predictive of cardiac event) 11. Smoking history 12. Repaired or unrepaired cyanotic heart disease. 13. Lesion-specific risk |

|

1. Poor maternal functional classes 3 and 4 or cyanosis 2. Maternal left heart obstruction 3. Low maternal oxygen saturation 4. Obstetric risk factors and abnormal uteroplacental flow 5. Mechanical prosthetic valve 6. Maternal cardiac event or decline in cardiac output during pregnancy 7. Tobacco and smoking 8. Anticoagulation therapy, cardiac medication multiple gestation 9. Lesion-specific risk factor |

The first four risk factors listed in Table 1 belong to CARPREG (Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy) risk index. According to CARPREG risk index, 1 point is given to each predictors and risk is classified.

The risk of maternal cardiac adverse event with zero risk factor is < 5%, with one risk factor is 27% and more than one risk factor being 75%.

Multidirectional Consideration

Often, tertiary care is required to manage these critical subsets. Psychological and social support is equally important to mothers going through pregnancy. Family and the patient should have detailed information about the risk, natural history, and recurrence chances (Fig. 1).

Obstetric complications often impose challenge in CHD women. Multiple pregnancies, pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH), eclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), anemia, and hypercoagulable state are important challenges.

World health Organization (WHO) classification provides another roadmap in assessing maternal cardiovascular risks (Table 3).

|

Abbreviations: ASD, atrial septal defect; BAV, bicuspid aortic valve; CER, cardiac event rate; LV, left ventricular/left ventricle; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MS, mitral stenosis; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PAH, pulmonary artery hypertension; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PS, pulmonary stenosis; RV, right ventricular/right ventricle; TAPVC, total anomalous pulmonary venous connection; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; VSD, ventricular septal defect; WHO, World Health Organization. |

|

Pregnancy risk is WHO I (Maternal mortality is not increased. Maternal CER 2.5–5%) |

|

1. Uncomplicated small or mild PS, PDA, mitral valve prolapse 2. Successfully repaired simple lesions (ASD, VSD, PDA, TAPVC) 3. Isolated atrial or ventricular ectopic beats |

|

Pregnancy risk is WHO II (Small increase in maternal mortality/moderate increase in morbidity, maternal CER 5.7–10.5%) |

|

1. Unoperated atrial and small ventricular defects 2. Repaired TOF 3. Most arrhythmias |

|

Pregnancy risk is WHO II–III (Intermediate increase in risk of maternal mortality and moderate to severe increase in morbidity, maternal CER 10–19%) |

|

1. Mild LV impairment 2. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy 3. Native or tissue valvular heart disease not considered WHO I or IV 4. Marfan’s syndrome without aortic dilation 5. Aorta < 45 mm in aortic disease with BAV 6. Repaired coarctation |

|

Pregnancy risk is WHO III (Significant increase in maternal mortality and severe morbidity, maternal CER 19–27%) |

|

1. Mechanical valve 2. Systemic RV with mild ventricular dysfunction 3. Fontan circulation 4. Cyanotic heart disease (unrepaired) 5. Other complex congenital heart disease 6. Aortic dilation 40–45 mm in Marfan’s syndrome 7. Aortic dilation 45–50 mm in aortic disease with BAV 8. Moderate mitral stenosis 9. Severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis |

|

Pregnancy risk WHO IV (Extremely high risk of maternal mortality. Maternal CER 40–100%) |

|

1. PAH of any cause 2. Severe systemic ventricular dysfunction (LVEF < 30%, NYHA III–IV), systemic RV dysfunction moderate to severe 3. Peripartum cardiomyopathy with LV dysfunction 4. Severe MS and symptomatic aortic stenosis 5. Marfan’s syndrome with aorta > 45 mm 6. BAV with aorta > 50 mm, TOF > 50 mm 7. Native severe coarctation |

Individual Risk Categorization and Management of Pregnancy with Congenital Heart Diseases

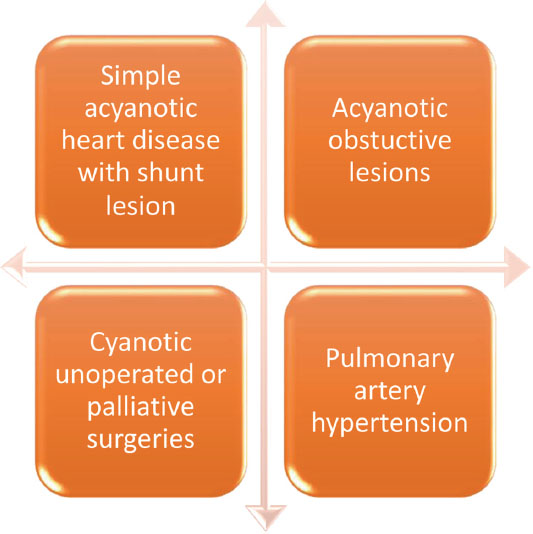

Congenital heart diseases in adults can be classified into 4 categories (Fig. 2) as listed below:

-

Fig. 2 GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension.

Fig. 2 GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension.

-

Simple acyanotic heart disease with shunt lesions

-

Acyanotic obstructive disease

-

Cyanotic heart disease (unoperated or palliative surgery or corrective surgery)

-

Congenital heart diseases with pulmonary artery hypertension

Obstetric implications, neonatal outcomes of individual CHDs are discussed in the following section.

Septal Defects

1. Repaired and Unrepaired Atrial Septal Defect

Maternal Effect

Unoperated atrial septal defect (ASD) is usually well tolerated during pregnancy. Often, ASD is diagnosed during pregnancy due to increase in cardiac output. One of the contraindications to pregnancy with ASD is PAH. Arrhythmia can be seen in uncorrected ASD due to atrial dilation.19– 21 Repaired ASD without residual lesion and normal ventricular function bear no extra risk during pregnancy.

Obstetric Risk and Management

Preeclampsia can complicate ASD in the form of increase left-to-right shunt. This increases right ventricular (RV) volume overload. Study done at the Netherlands and Belgium showed that women with an unrepaired ASD are at increased risk of neonatal complication in the form of premature birth and intrauterine growth retardation.21

In an uncomplicated ASD, twice follow-up during pregnancy is sufficient. ASD closure during pregnancy is usually not indicated. Care should be taken to prevent paradoxical embolization. Spontaneous vaginal delivery is permissible.

2. Repaired and Unrepaired Ventricular Septal Defects

Small to moderate unrepaired ventricular septal defects (VSDs) are well tolerated during pregnancy. Large VSD with severe PAH is discussed with PAH section. Repaired VSDs without residual lesion and normal pulmonary artery (PA) pressure can have normal pregnancy outcome.22 Normal vaginal delivery can be attempted.

3. Atrioventricular Septal Defects

Unrepaired atrioventricular septal defects (AVSDs) with severe PAH is classified under WHO class IV risk assessment. Mild to moderate atrioventricular (AV) valve regurgitation with partial ASD is classified under WHO class II. Severe AV valve regurgitation can cause cardiac decompensation during pregnancy. Hence it should be surgically repaired prior to conception. Repaired AV canal defect without residual lesion or AV valve regurgitation is tolerated well during pregnancy.23

Obstructive Lesions

4. Coarctation of Aorta

Unrepaired severe coarctation of the aorta (COA) is a contraindication and classified under WHO class IV risk assessment.18 It is associated with systemic hypertension and possibility of aneurysm formation and dissection. Because of COA, there is a restriction of uterine flow and placental hypoperfusion, which further exaggerate with antihypertensive medications. Hence native COA and residual COA should be treated in advance. Repaired COA patients without residual lesion can have pregnancy.24 25

Management

Blood pressure should be closely monitored. Hypertension may be seen even in absence of residual COA. Residual COA with uncontrolled hypertension might need percutaneous intervention. Risk of dissection is higher. β blockers and calcium channel blockers are used for treatment of hypertension. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are containdicated. Covered stents are advisable to lower risk of dissection.26 Spontaneous delivery is preferred in an uncomplicated and treated COA.

5. Pulmonary Stenosis and Pulmonary Regurgitation

Mild to moderate pulmonary stenosis (PS) is well tolerated during pregnancy. Severe PS at any point of time during pregnancy should be judged with symptoms and RV function. Severe PS should be treated prior to conception. Balloon valvuloplasty should be done in case of severe symptomatic PS.27– 29

Severe pulmonary regurgitation (PR) can lead to RV dysfunction, and hence it is an independent risk factor for maternal complication. RV dysfunction associated with severe PR should be treated in prior. It is closely associated with arrhythmias.30

Management

Twice during pregnancy, follow-up is satisfactory in case of mild to moderate PS. Balloon valvotomy can be done in case of severe PS detected during pregnancy.29 Normal vaginal delivery is possible in case of mild to moderate PS. Cesarean section should be performed in case of New York Heart Association (NYHA) classes III and IV with severe PS.

6. Aortic Stenosis

Congenital aortic stenosis (AS) occurs commonly due to bicuspid aortic valve (BAV). BAV is associated with ascending aorta (AAO) dilation.

Aortic valve area less than 1.5 cm2 and left ventricular (LV) outflow tract gradient more than 30 mm Hg are associated with adverse maternal event. Exercise testing should be performed in asymptomatic patients before pregnancy to confirm asymptomatic status and evaluate appropriate exercise response. Pregnancy should be avoided in case of severe AS, LV dysfunction, and inappropriate exercise response.18 In severe AS, fetal and maternal mortalities are 30% and 17%, respectively. Hence it should be treated prior to conception.31 Complications are seen predominantly in patients with symptomatic severe AS.32

Management

If severe AS is detected during pregnancy, balloon aortic valvotomy is advised in case of noncalcified valves. Close monthly or bimonthly follow-up is indicated. Cesarean section is indicated in severe AS. Afterload-reducing agents should be avoided during anesthesia. Vaginal delivery is advised in case of mild to moderate AS. AAO size more than 50 mm should be treated prior to pregnancy.

Cyanotic Heart Diseases

7. Tetralogy of Fallot

This condition should be operated prior to pregnancy. If resting saturation is less than 85%, significant maternal and neonatal complications can be encountered. Maternal complications such as endocarditis, heart failure, and thromboembolism can occur in 30% of cases and chance of live birth is only 12%. If saturation is more than 90%, chance of fetal outcome improves to 90%. Pregnancy should be discouraged if saturations are less than 85%.33

Postoperative Tetralogy of Fallot

Postoperative tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is well tolerated if ventricular function is preserved. Symptomatic patients with PR and ventricular dysfunction can have adverse maternal outcome. Therefore, pulmonary valve replacement should be performed prior to conception. Arrhythmias and heart failure are noticed in 12% of population.34

Management

Unoperated TOF patient needs close follow-up. During pregnancy, bedrest and supplemental oxygenation are advised. Compression stockings are advised to prevent venous stasis, thrombosis, and paradoxical embolization. Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) can be commenced. Good hydration should be maintained. Air filter and endocarditis prophylaxis are advised. In postoperative TOF patients, bimonthly follow-up for ventricular function, functional class, and arrhythmia should be performed.

8. Transposition of Great Arteries

Unoperated transposition of great arteries (TGAs) is rare to survive to adulthood but seen in developing countries. Pregnancy is contraindicated in these patients due to possibility of adverse maternal and neonatal event.

Senning or Mustard Surgery

Pregnancy outcome depends on RV function and tricuspid regurgitation. Pregnancy should be discouraged if functional class is more than 2, more than mild RV dysfunction, and tricuspid regurgitation seen. Heart failure and arrhythmia are seen during pregnancy.35

Management

Heart failure should be treated with diuretics and bedrest. ACE inhibitors are contraindicated. Hydralazine can be given to reduce afterload. In case of RV dysfunction, cesarean section is advised.

Arterial switch surgery: Outcome of pregnancy appears good in cases of postoperative arterial switch surgery.36

9. Ebstein’s Anomaly37– 39

Ebstein’s anomaly is frequently associated with ASD and preexcitation syndrome. Less than severe tricuspid regurgitation and good RV function are favorable toward pregnancy outcome.37 Patients can deteriorate due to arrhythmia. Risk of paradoxical embolization exists in presence of ASD.

Management

Symptomatic patients with cardiomegaly and severe TR should be treated prior to pregnancy. Severe TR and heart failure, if seen during pregnancy, should be managed with diuretics and bedrest. Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome can be treated with β-blockers. Digoxin should be avoided in Ebstein’s anomaly.

10. Congenital Corrected Transposition of Great Arteries

Pregnancy outcome largely depends on RV function, symptomatic status, and underlying physiology. Pregnancy should be discouraged in case of RV dysfunction and tricuspid regurgitation. Arrhythmia, irreversible RV dysfunction, and heart failure are noticed during pregnancy.40 41

11. Fontan Surgery42– 45

These patients belong to WHO class III–IV in risk assessment and should be counseled carefully. Although successful pregnancies are reported in the literature, cases should be individualized prior to conception. These patients are highly preload dependent, and detailed preconception evaluation is mandatory in form of electrocardiogram (ECG), echocardiography (echo), liver function test, and functional class. Cases with saturation less than 85%, ventricular dysfunction, right ventricle as systemic ventricle, symptomatic status, and with arrhythmia should be discouraged against pregnancy. Often, these patients receive anti coagulation therapy; hence, switch to LMWH is needed. Paradoxical embolization is possible in presence of fenestration. Ventricular dysfunction, arrhythmias, and paradoxical embolization can complicate pregnancy and aid maternal morbidity and mortality.

Management

Close surveillance is indicated. Anticoagulation is switched to LMWH. ACE inhibitors are contraindicated. If bed rest is advised, compression stockings should be applied to avoid venous stasis. Diuretic might be needed in case of ventricular dysfunction or AV valve regurgitation. Vaginal delivery is preferred. Preload and systemic vascular resistance should be maintained, if cesarean section is required. Offspring risk of premature delivery and fetal death is up to 50%.

12. Pulmonary Artery Hypertension and Eisenmenger’s Syndrome46– 49

Pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH) in CHDs can be due to large post-tricuspid shunts or complex cyanotic heart lesions with increased pulmonary blood flow. Unoperated, these conditions cause pulmonary vascular obstructive disease. High maternal mortality is reported up to 50%, predominantly during last trimester and postpartum in women with CHD. Maternal mortality is seen due to PA crisis, pulmonary thrombosis, or refractory RV dysfunction. Reduction in systemic vascular resistance and preload leads to increase in cyanosis.

Management

Pregnancy is contraindicated. PAH comes under WHO class IV risk factor. If pregnancy occurs, termination is advised. Afterload reduction can occur due to anesthesia that can deteriorate the condition further. Tertiary care center is appropriate to provide best care.

If termination is not possible, patient should be stabilized to maintain adequate cardiac output and saturations. This can be done by maintaining hydration, avoiding acidosis, and systemic vascular resistance. Paradoxical embolization should be prevented by air filter.

Medical therapy such as Bosentan should be continued after explaining the teratogenic risk to the couples. IV prostacyclin, although not available in India, can be used during delivery to provide hemodynamic stability. Appropriate anticoagulation is advocated (LMWH) in selected cases.

Conclusion

Each case should be individualized and detail evaluation must be performed. Case to case basis risk assessment should be done. Multi modal approach is often warranted. Counselling regarding maternal risk, fetal risk and recurrence chances should be executed. Pregnancy termination is offered if chance of maternal morbidity or mortality exist. Mode of delivery must be planed in advance according to cardiac illness and obstetric indications.

References

- Prevalence of congenital anomalies in an Indian maternal cohort: healthcare, prevention and surveillance implications. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166408.

- [Google Scholar]

- Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(21):2241-2247.

- [Google Scholar]

- Congenital malformations in the newborn population: a population study and analysis of the effect of sex and prematurity. Pediatr Neonatol. 2015;56(01):25-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Updated National Birth Prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004-2006. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2010;88(12):1008-1016.

- [Google Scholar]

- Task force 1: the changing profile of congenital heart disease in adult life. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(05):1170-1175.

- [Google Scholar]

- The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(12):1890-1900.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hamatologic system. In: Maternal physiology. Vol 25. Washington, DC: CREOG; 1985. p. :7-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serial study of factors influencing changes in cardiac output during human pregnancy. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:H1060-H1065. (4 Pt 2)

- [Google Scholar]

- Alterations in cardiovascular physiology during labor. Obstet Gynecol. 1958;12(05):542-549.

- [Google Scholar]

- Haemodynamic changes during the early puerperium. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987;294:1065. (6579)

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy and adult congenital heart disease. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2007;5(05):859-869.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plasma volume in normal first pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1973;80(10):884-887.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early pregnancy changes in hemodynamics and volume homeostasis are consecutive adjustments triggered by a primary fall in systemic vascular tone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169(06):1382-1392.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prospective multicenter study of pregnancy outcomes in women with heart disease. Circulation. 2001;104(05):515-521.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy in young women with congenital heart defects. In: Textbook of Moss and Adams Heart Diseases in Infants (9th ed). Children and Adolescents; In:

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk Prediction of cardiovascular complications in pregnant women with heart disease. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2016;106(04):289-296.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2018 ESC guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(34):3165-3241.

- [Google Scholar]

- ESC guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(24):3147-3197.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of pregnancy outcomes in women with repaired versus unrepaired atrial septal defect. BJOG. 2009;116(12):1593-1601.

- [Google Scholar]

- Atrial septal defects in the adult: recent progress and overview. Circulation. 2006;114(15):1645-1653.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy outcome in women with repaired versus unrepaired isolated ventricular septal defect. BJOG. 2010;117(06):683-689.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac complications relating to pregnancy and recurrence of disease in the offspring of women with atrioventricular septal defects. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(23):2581-2587.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcome of pregnancy in patients after repair of aortic coarctation. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(20):2173-2178.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coarctation of the aorta: outcome of pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(06):1728-1733.

- [Google Scholar]

- Single therapeutic catheterization for treatment of late diagnosed native coarctation of aorta using a covered stent. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(03):153-155.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of pulmonary stenosis on pregnancy outcomes—a case-control study. Am Heart J. 2007;154(05):852-854.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of valvular heart disease on maternal and fetal outcome of pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(03):893-899.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy outcome in women with congenital heart disease and residual haemodynamic lesions of the right ventricular outflow tract. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(14):1764-1770.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk of complications during pregnancy in women with congenital aortic stenosis. Euro Cardiovascular Disease. 2007;391:108-110.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk of pregnancy in moderate and severe aortic stenosis: from the multinational ROPAC registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(16):1727-1737.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy, fertility, and recurrence risk in corrected tetralogy of Fallot. Heart. 2005;91(06):801-805.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcomes of pregnancy in women with tetralogy of Fallot. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(01):174-180.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of pregnancy on the systemic right ventricle after a Mustard operation for transposition of the great arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(02):433-437.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy outcomes in women with transposition of the great arteries and arterial switch operation. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106(03):417-420.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ebstein’s anomaly in pregnancy: maternal and neonatal outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(02):278-283.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcome of pregnancy in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(07):820-824.

- [Google Scholar]

- Right ventricular dysfunction in congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(09):1116-1119, A10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy and the various forms of the Fontan circulation. Heart. 2007;93(02):152-154.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thromboembolic complications after Fontan operations. Circulation. 1995;92(09):II287-II293. Suppl)

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy and delivery in women after Fontan palliation. Heart. 2006;92(09):1290-1294.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), endorsed by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Eur Heart J. 2009;30(20):2493-2537.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcome of pulmonary vascular disease in pregnancy: a systematic overview from 1978 through 1996. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31(07):1650-1657.

- [Google Scholar]