Translate this page into:

Predictors of Post-catheterization Femoral Artery Pseudoaneurysm

*Corresponding author: Sama Rajashekhar, Department of Cardiology, Nizams Institute of Medical Sciences, Panjagutta, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. samarajashekharreddy121@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Rajashekhar S, Kumar A. Predictors of post-catheterization femoral artery pseudoaneurysm. Indian J Cardiovasc Dis Women 2023;8:126-30.

Abstract

Objectives:

To compare the affected patients with the age- and sex-matched patients in the control group.

Materials and Methods:

All patients who had undergone PCI, left heart catheterization, or coronary angiography between July and November 2022 were prospectively recruited. We included 247 patients in our study who underwent cardiac catheterization via femoral access.

Results:

The incidence of FAP after a diagnostic catheterization was 5.97% and 8.69% after an interventional procedure. The mean age of the patients with FAP was 54.06 ± 15.04 years and 62.5% patients were females in the affected group. In FAP group, 14 patients (87.5%) had hypertension, 8 patients (50%) had diabetes, and 37.5% were had obesity. The systolic blood pressure was 145.38 ± 29.99 mmHg, while the diastolic blood pressure was 86 ± 14.59 mmHg. Data obtained from computed tomography scanning showed that the arterial wall of the CFA was healthy in 11 patients (68.5%), while diffuse atherosclerosis was detected in 5 (31.5%) patients. In 69% of the patients, FAPs were connected to the CFA and in 31% patients to the superficial femoral artery (SFA). In 38% (6) patients partial thrombosis of the pseudoaneurysm sac observed.

Conclusion:

FAP is a common vascular complication after a diagnostic procedure or percutaneous cardiac catheterization, and its prevalence is likely to rise.

Keywords

Femoral artery pseudoaneurysm

Catheterization

Predictors

ABSTRACT IMAGE

INTRODUCTION

Femoral artery pseudoaneurysm (FAP) is one of the most common complications after femoral arterial access for coronary angiography or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Pseudoaneurysm also known as “false aneurysm” occurs when there is a breach to the arterial wall, consists of an outpouching of 1 or 2 layers of the vessel wall whereas true aneurysm involves all the three layers of the vessel including the intima, media, and adventitia. The breach in vessel wall causes accumulation of blood between tunica media and adventitia and under the influence of sustained arterial pressure it forms a perfused sac that communicate with the arterial lumen.[1]

The incidence of FAP ranges from 0.2% to 8% depending on the procedure performed either diagnostic catheterization or coronary or peripheral intervention.[2,3] Risk factors are patient related, more common in female sex, hypertensives, obesity, use of antiplatelet, anticoagulants, and procedure related such as use of larger sheath size, puncture site below common femoral artery (CFA), and emergency procedures.[4]

The presence of unusual pain or groin swelling after catheterization is the most common presentation of a FAP. Physical examination may reveal swelling in the groin, marked tenderness, mass, bruising, thrill, or bruit. Complications such as neuropathy, limb ischemia, claudication, venous thrombosis results from compression of the femoral nerve and vessels by enlarging pseudoaneurysm. Rupture is a catastrophic event, associated with severe pain and hemodynamic instability.[5] The preferred diagnostic test is a duplex ultrasound with B mode imaging, color flow imaging, and Doppler pulse wave analysis. Duplex ultrasound provides accurate anatomical information, differentiates FAP from hematomas and arterio-venous fistulae, and estimates velocities within the sac and neck.[6] The gold standard in diagnosis continues to be conventional angiography.

Management options include observation, ultrasound-guided compression, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection or surgery depending on the size of the aneurysm. For small (<2 cm) and stable pseudoaneurysm, observation with weekly duplex ultrasound until thrombosis occurs is advised along with stopping anticoagulants, avoiding bending movements and lifting heavy weights.[7] If the size is more than 2 cm or increasing on repeat scan, short neck width (<4 mm), develops within 7 days of femoral access, requiring continuation of anticoagulant and associated with significant pain then we have to treat aggressively. Ultrasound guided compression advised for small pseudoaneurysms, success rate of which is 63–88%. Compression is advised with ultrasound probe in 10 min cycles, an average of 37 min required to achieve thrombosis. The patient should lie flat for 2–4 h following compression. An ultrasound must be conducted again in 24–48 h to ensure that the pseudoaneurysm has not reopened. Ultrasound guided thrombin injection is performed under local anesthesia. Under duplex imaging, diluted thrombin is directly administered into the pseudoaneurysm, and thrombosis is monitored. After the procedure, the patient should stay in bed for 12 h. Distal embolization (0.5%) is the most frequent complication, with a success rate of 93–97%. Surgery is necessary for rapidly enlarging pseudoaneurysms, patients having compressive symptoms.[8,9] In our study, we compared the affected patients with the age- and sex-matched patients in the control group. For patients in the control group also Duplex scan was done to exclude the presence of FAP and same data were collected as for patients with a documented FAP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study setting

All patients who had undergone PCI, left heart catheterization, or coronary angiography between July and November 2022 were prospectively recruited.

Clinical examination

Local examination of groin was done in all patients before and after the procedure including auscultation. The groin sheath removal done immediately after diagnostic procedure and 4 h after discontinuation of heparin in patients undergone interventional procedure. All patients had manual compression for 10 min, or until the puncture site bleeding ceases, and then the compression bandage was worn for an additional 6 h.

Radiological examination

Duplex scanning was performed using Sonoline Elegra V6.0 (Siemens Corporation, Munich, Germany), ATL HDI 5000 and HP Sonos 2000 (Philips, Eindhoven, Netherlands) systems. All had high resolution broadband width linear array transducers L5-7/10 MHz. Findings on DUS which indicate pseudoaneurysm would consist of a mass separate from the affected artery, presence of flow called a “to-and-fro flow” between the arterial lumen and sac.

We advised computed tomography angiogram of bilateral lower limbs in patients diagnosed to have pseudoaneurysm to look for the condition of the vessel wall either healthy or atherosclerotic and the following data collected.

Data collection

The following data are collected such as baseline parameters, risk factors, and onset of symptoms after the procedure within 3 days, 3–7 days or >7 days, blood pressure at the time of procedure, and type of the procedure: Diagnostic or intervention, Gauge of introducer sheath, body mass index (weight/height2 [kg/m2]), and examination of the pedal pulsations.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyses using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (IBM corporation, New York, USA). The incidence of FAP is given as percentage of all included patients. Chi-square test was used to compare the gender distribution, presence of comorbidities, obesity and catheter size between two groups. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

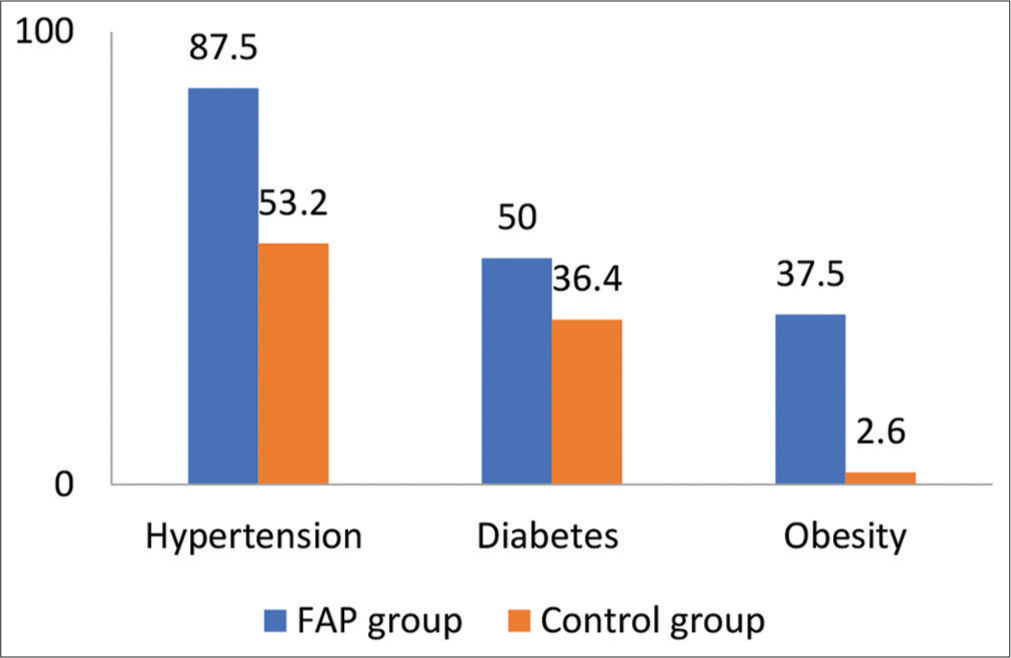

We included 247 patients in our study who underwent cardiac catheterization via femoral access from June 2022 to November 2022 in our hospital. In this 201 patients undergone diagnostic procedure and 46 undergone interventional procedure. In our study, 16 patients had FAP after the procedure in 247 patients (6.5%), 12 patients (75%) had developed after a diagnostic catheterization, and 4 patients (25%) developed after an interventional procedure. The incidence of FAP after a diagnostic catheterization was 5.97% and 8.69% after an interventional procedure. The mean age of the patients with FAP was 54.06 ± 15.04 years and 62.5% patients were females in the affected group [Table 1 and Figure 1]. In FAP group, 14 patients (87.5%) had hypertension, 8 patients (50%) had diabetes, and 37.5% were had obesity. The systolic blood pressure was 145.38 ± 29.99 mmHg, while the diastolic blood pressure was 86 ± 14.59 mmHg. About 80% patients (13 people) developed pseudoaneurysm within the 3 days and all the affected patients had groin swelling and bruit on auscultation [Figure 2]. Data obtained from computed tomography scanning showed that the arterial wall of the CFA was healthy in 11 patients (68.5%), while diffuse atherosclerosis was detected in 5 (31.5%) patients. In 69% of the patients, FAPs were connected to the CFA and in 31% patients to the superficial femoral artery (SFA). In 38% (6) patients partial thrombosis of the pseudoaneurysm sac observed. Doppler waveform in the pedal arteries was triphasic in all examined patients. Female gender, hypertension, and obesity were more frequent in patients with FAP compared to controls. Diagnostic studies, use of antiplatelet therapy were also more common in the FAP group. By univariate analysis, hypertension, and obesity significantly associated with increased risk for developing FAP [Table 2].

| Variable | Category | Group A | Group B | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Age | Mean | 54.06 | 15.04 | 52.85 | 12.84 | 0.53a |

| Range | 26–77 | 18–82 | ||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Sex | Males | 6 | 37.5% | 103 | 44.6% | 0.58b |

| Females | 10 | 62.5% | 128 | 55.4% | ||

Group A: Patients with femoral artery pseudo aneurysms, Group B: Patients without femoral artery pseudoaneurysm

- Gender-wise distribution between femoral artery pseudoaneurysm and control group.

- Comparison of risk factors among femoral artery pseudoaneurysm and control groups.

| Risk factor | FAP group (n=16) | Control group (n=231) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54.06±15.04 | 52.85±12.84 | NS |

| Females | 10 (62.5) | 62 (27) | |

| Hypertension | 14 (87.5) | 123 (53.2) | 0.008 |

| Diabetes | 8 (50) | 84 (36.4) | NS |

| Smoking | 4 (25) | 70 (30) | NS |

| Obesity | 6 (37.5) | 6 (2.6) | 0.001 |

| Sheath size (7F) | 1 (6.1) | 14 (6.2) | NS |

| Multiple punctures | 7 (43.75) | 38 (17.2) |

FAP: Femoral artery pseudoaneurysm

DISCUSSION

The frequency of vascular complications following catheterization ranged from 0.2% to 8% in publications. Vascular complications after diagnostic cardiac catheterization were reported to occur at a rate of 3.4% by Tavris et al.[10] and in another series[11] 2–6% is the risk of vascular problems in interventional catheter-based procedures. In a meta-analysis, femoral artery access procedures resulted in 3.3% vascular complications, of more than 35,000 patients.[12] Due to the rising frequency of radiological and cardiovascular interventions, use of larger sheath sizes, longer catheter dwell times, and the requirement of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapies during these procedures, the incidence of local-puncture related complications is likely to rise in the coming future.

16 patients had FAPs in our study. The majority of patients with FAP’s had undergone diagnostic procedure. In our investigation, there was a 6.5% incidence of FAP, which is consistent to the ranges noted in other studies that have been published. The incidence of FAP is more (5.97%) in our study after diagnostic procedure. We attribute this to two factors that contribute to the high incidence of FAP’s after diagnostic catheterization. The vast majority of operators perform femoral puncture by palpation and examination of surface indicators such as the inguinal crease and the anterior superior iliac spine. Only a few operators use fluoroscopic guidance to execute the puncture to determine the level of the femoral head. Obese persons may have an extra inguinal skin fold that punctures the SFA as a consequence. The second aspect is the typical practice of removing the sheath immediately after the operation in the cath lab. Active clotting time (ACT) testing is only required by a tiny number of surgeons prior to removing the groyne sheath during diagnostic angiography, despite the fact that the majority of patients are given heparin at the start of the surgery. The end effect might be a “superfluous” inguinal skin fold perforating the SFA in obese people. The second reason is that it is usual practice in the cath lab to remove the sheath shortly after the operation. The majority of patients are administered heparin prior to the surgery, but a few of operators order an ACT test before removing the groyne sheath following diagnostic angiogram procedure. In some cases, protamine may be required to antagonise the effects of heparin. Another rationale is that groyne sheaths are normally evacuated by cath lab technicians following diagnostic procedures, and after PCI, the sheathing is usually removed by the resident in the ICU, with greater care. Obesity and hypertension were identified to be contributing risk factors for the development of FAPs. FAPs were also associated with an improper low puncture location and numerous puncture attempts. Age, other conventional atherosclerosis risk factors, introducer sheath size, interventional method, prior history of catheterization at the same location, and early mobilization following CA, on the other hand, had no significant relevance.[13] In the literature, procedural risk factors for FAP include interventional rather than diagnostic techniques, catheterization of both arteries and vein, low femoral puncture resulting in catheterization of such SFA or profunda, and inappropriate compression postoperative. Obesity, anticoagulant use, hemodialysis, and calcified femoral arteries have all been described as patient-related variables.

CONCLUSION

FAP is a common vascular complication after a diagnostic procedure or percutaneous cardiac catheterization, and its prevalence is likely to rise. Perforations underneath the CFA, high blood pressure, and even being overweight or obese are the best predictors of FAP. The use of a 7F sheath, early mobilization, and previous catheterization did not predict the development of a pseudoaneurysm. It is strongly advised to lance under fluoroscopic guidance.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Audio summary available at

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Efficacy and safety of percutaneous treatment of iatrogenic femoral artery pseudoaneurysm by biodegradable collagen injection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1297-304.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peripheral vascular complications following coronary interventional procedures. Clin Cardiol. 1995;18:609-14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Predicting vascular complications in percutaneous coronary interventions. Am Heart J. 2003;145:1022-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prophylactic ipsilateral superficial femoral artery access in patients with elevated risk for femoral access complications during transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:e123-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Complications associated with femoral cannulation during minimally invasive cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103:1927-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasonographic evaluation of complications related to transfemoral arterial procedures. Ultrasonography. 2018;37:164-173.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algorithm of treatment policy for a femoral artery false aneurysm. Angiol Sosud Khir. 2018;24:195-200.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endovascular treatment of isolated degenerative superficial femoral artery aneurysm. Ann Vasc Surg. 2018;49:311.e11-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puncture treatment of pseudoaneurysms of femoral arteries with the use of human thrombin. Angiol Sosud Khir. 2016;22:62-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk of local adverse events by gender following cardiac catheterization. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:125-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arterial puncture closing devices compared with standard manual compression after cardiac catheterization-systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;291:350-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vascular complications associated with arteriotomy closure devices in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary procedures-a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1200-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incidence and predictors of post-catheterization femoral artery pseudoaneurysms. Egypt Heart J. 2013;65:213-21.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]