Translate this page into:

Myocardial Infarction with Nonobstructive Coronary Artery (MINOCA)

R. Archana, NIMS Punjagutta, Hyderabad – 500082 India remalaarchana@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA) is diagnosed in almost equal to 5 to 6% of patients who present with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Causes of MINOCA are varied. Appropriate diagnosis and evaluation is important to uncover the correct cause and prescribe specific therapies to treat the underlying cause.

Women with evidence of MINOCA are being increasingly recognized. The mechanisms underlying MINOCA, such as coronary microvascular spasm, represent a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to medical fraternity, as there is neither a uniform nor comprehensive diagnostic strategy for accurate risk stratification, in the present scenario, for these patients.

Here, we are reporting a case of MINOCA, which is rare and incompletely evaluated.

Keywords

MI-NOCA—myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronaries,

NSTEMI—non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Introduction

Ischemic heart disease is predominant cardiovascular cause of death in women. Myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA) is defined as acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in the absence of (≥ 50% stenosis) obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) in any artery.1 2

Patients presenting with MINOCA are usually younger than patients with AMI-CAD.3 Among patients presenting with AMI, MINOCA is twice as frequent in women than men, whereas AMI is more frequent in men.4 5

The traditional CAD risk factors and clinical features prevalent also vary among patients with MINOCA versus AMI-CAD. MINOCA patients have a lower prevalence of dyslipidemia than their counterparts with AMI-CAD.6 7 Other traditional CAD risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, tobacco abuse, and a family history of myocardial infarction, are less frequent in MINOCA patients.4 5

MINOCA is a working diagnosis that has been increasingly described to be caused due to mechanisms contributing to ischemia, such as coronary spasm, coronary microvascular disorders, coronary plaque rupture, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, and/or coronary emboli.8 Conventional coronary angiography tends to miss the etiology behind the myocardial injury in these patients; hence, invasive coronary reactivity testing is needed to establish the diagnosis.

Case Report

A 56-year-old female known case of hypertension came with angina and shortness of breath (SOB) of 1-day duration.

Patient developed sudden-onset chest pain, retrosternal, which lasted for 40 minutes. It started at rest, increased with minimal activity, relieved with sublingual nitrate to some extent, and associated with radiation to left arm and jaw and diaphoresis. She also had SOB of 1-day duration, which started with minimal exertion (New York Heart Association [NYHA] functional class [FC] III). There was no history of orthopnea or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND) episodes. No other cardiac complaints were recorded.

There was history of angina episodes in the past 2 years for which she went to hospital. She was given intravenous (IV) or sublingual nitrates which relieved her pain. She was on treatment for hypertension since the past 12 years and for migraine since the past 8 years. The patient is a homemaker by occupation. She consumes a mixed diet. There was no history of alcohol intake, smoking, or tobacco chewing. No family history of any cardiac disease was present.

On examination, patient was conscious, coherent, and oriented. Her body mass index (BMI) is 30.4 kg/m2. Temperature was 98.6 °F. Pulse rate was 96 beats per minute (BPM), regular in rhythm; blood pressure (BP) was 150/90 mm Hg in right upper limb in supine position. Breath rate was 18 cycles/min and O2 saturation was 98% while breathing room air. There was no anemia, jaundice, cyanosis, clubbing, pedal edema, or lymphadenopathy. On cardiovascular (CVS) examination, jugular venous pressure (JVP) had normal pressure and normal waveforms. Apical impulse was in left fifth intercostal (ICS) half inch medial to midclavicular line, LV type, and localized impulse. S1 and S2 were normal in intensity and with normal spilt. LV S3 and S4 were not audible. No added sounds were appreciated. Other systems examination were normal.

Investigations:

-

Chest X-ray (CXR) (Fig. 1).

-

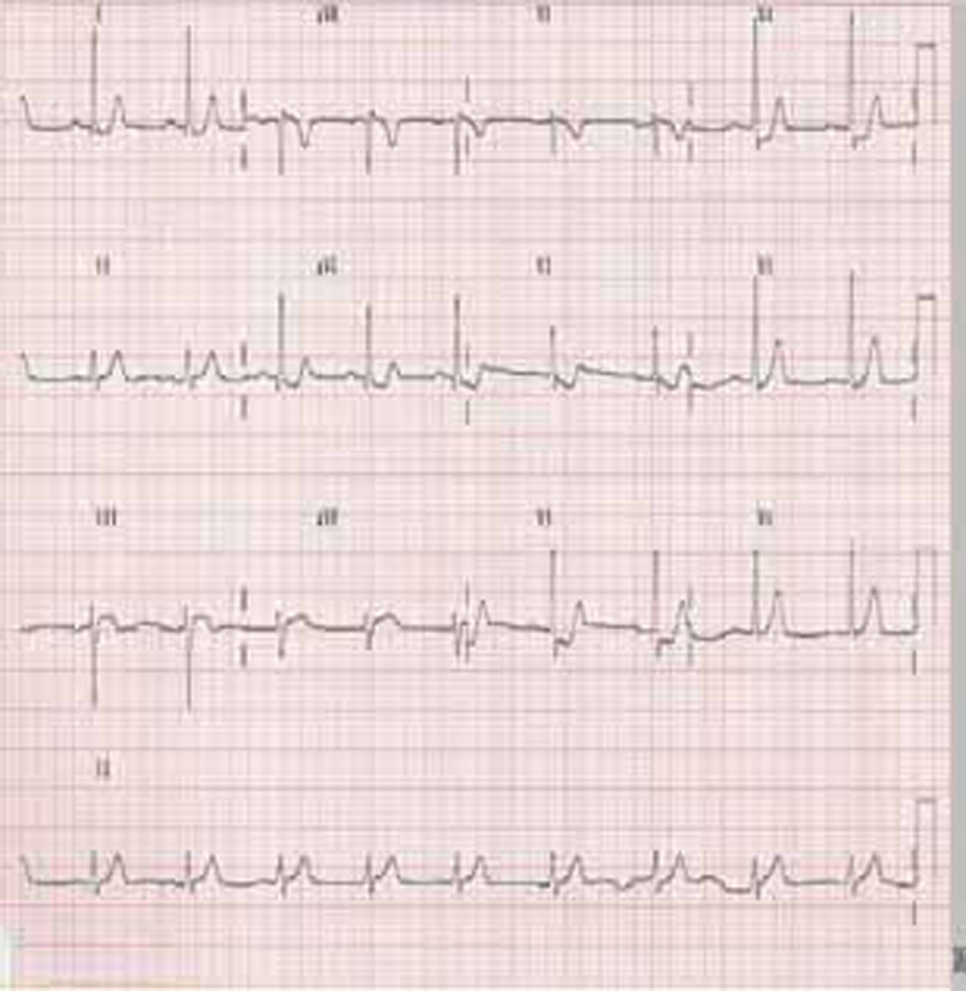

Electrocardiogram (Fig. 2).

-

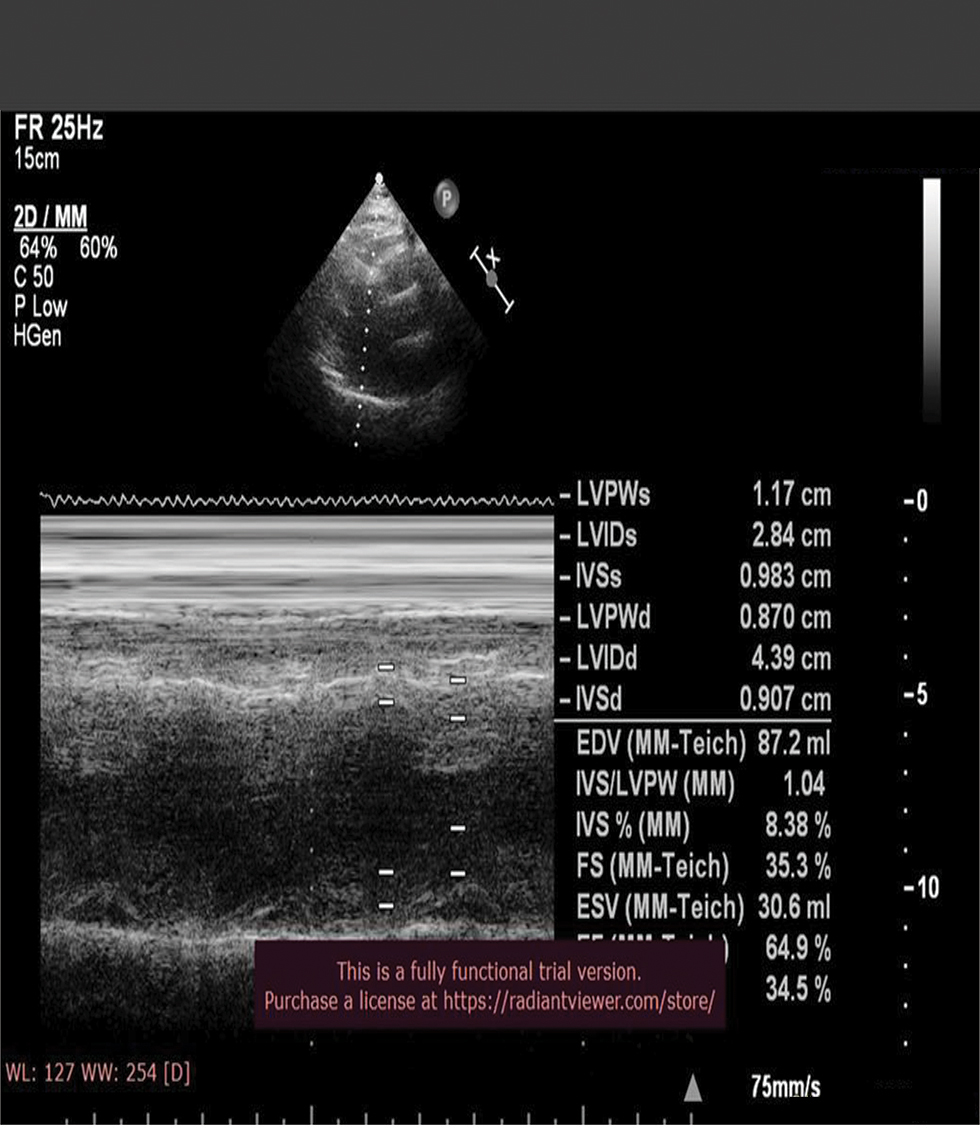

2D echo (Fig. 3)

-

Laboratory investigations (Table 1).

-

Others.

-

Fig. 1 Chest X-ray (CXR) posteroanterior (PA) view.

Fig. 1 Chest X-ray (CXR) posteroanterior (PA) view.

-

Fig. 2 Electrocardiogram.

Fig. 2 Electrocardiogram.

-

Fig. 3 Echo image showing normal left ventricular (LV) function.

Fig. 3 Echo image showing normal left ventricular (LV) function.

-

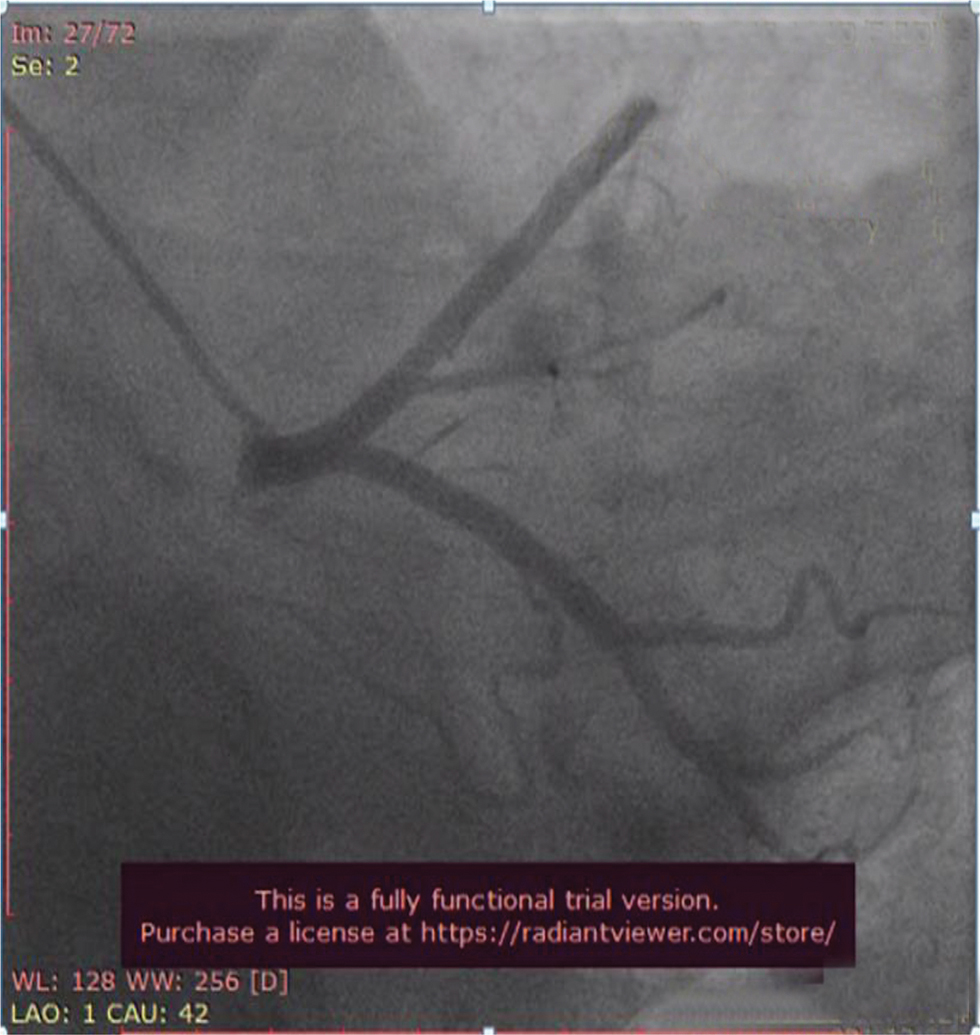

Fig. 4 Coronary angiogram (CAG) in left anterior oblique (LAO) caudal view showing normal proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery and proximal left circumflex artery (LCX) which are normal.

Fig. 4 Coronary angiogram (CAG) in left anterior oblique (LAO) caudal view showing normal proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery and proximal left circumflex artery (LCX) which are normal.

-

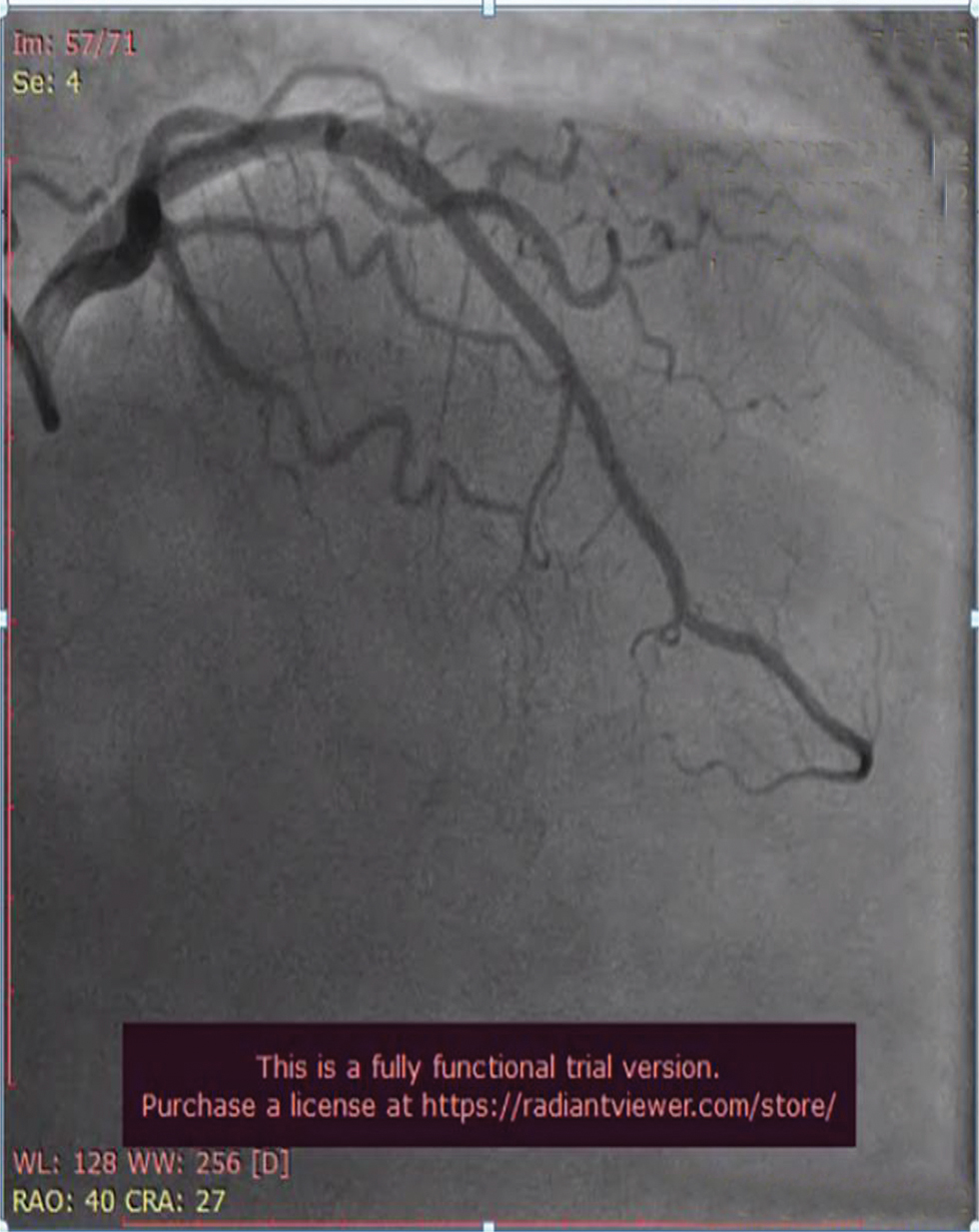

Fig. 5 Coronary angiogram (CAG) in right anterior oblique (RAO) cranial view showing normal mid and distal left anterior descending (LAD) artery.

Fig. 5 Coronary angiogram (CAG) in right anterior oblique (RAO) cranial view showing normal mid and distal left anterior descending (LAD) artery.

-

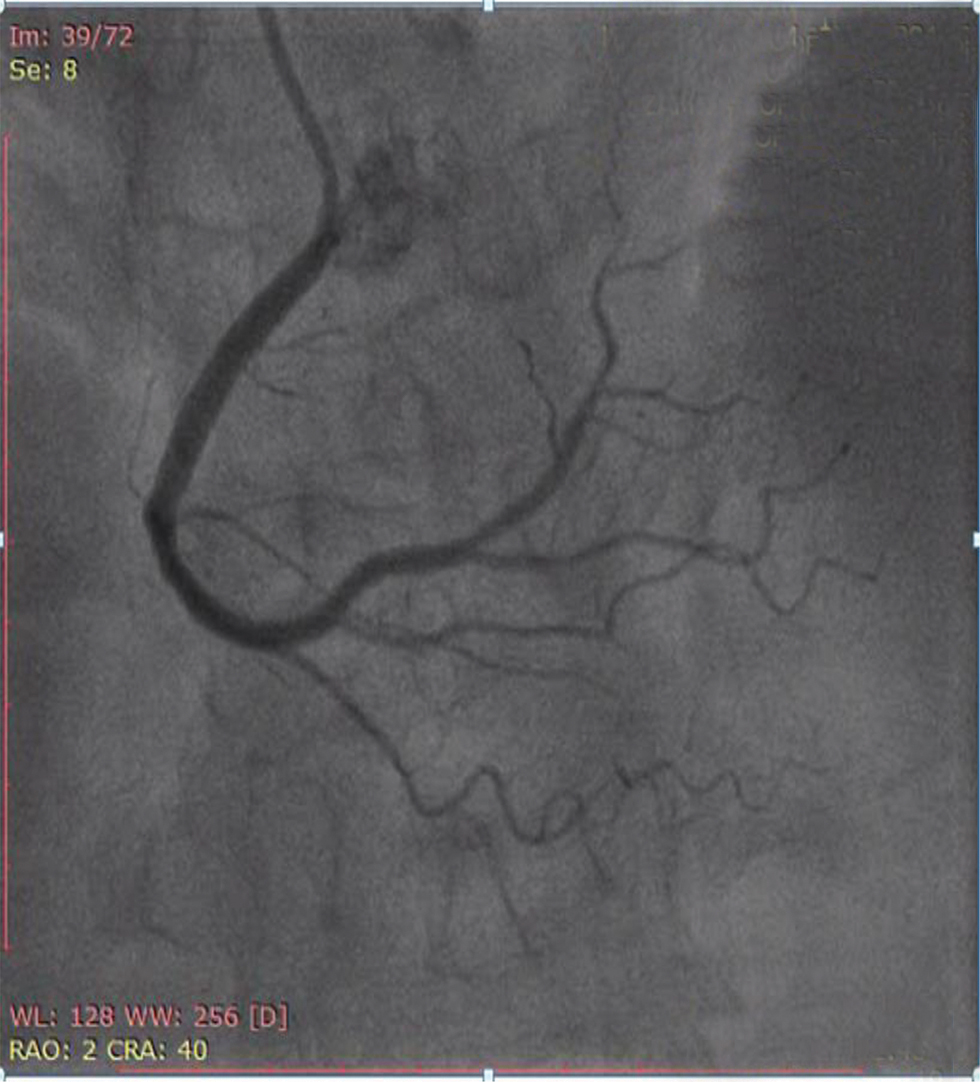

Fig. 6 Coronary angiogram (CAG) in anteroposterior (AP) cranial view showing normal right coronary artery (RCA).

Fig. 6 Coronary angiogram (CAG) in anteroposterior (AP) cranial view showing normal right coronary artery (RCA).

-

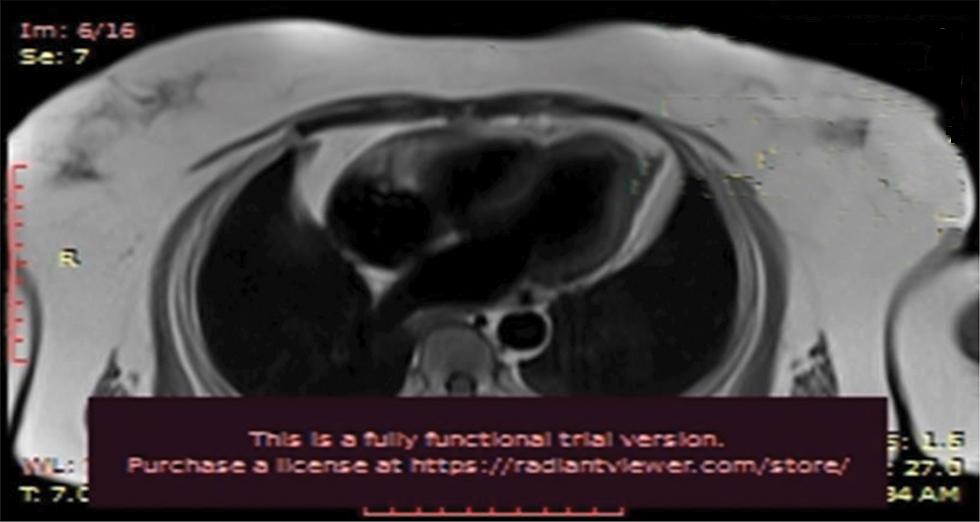

Fig. 7 Cardiac MRI.

Fig. 7 Cardiac MRI.

-

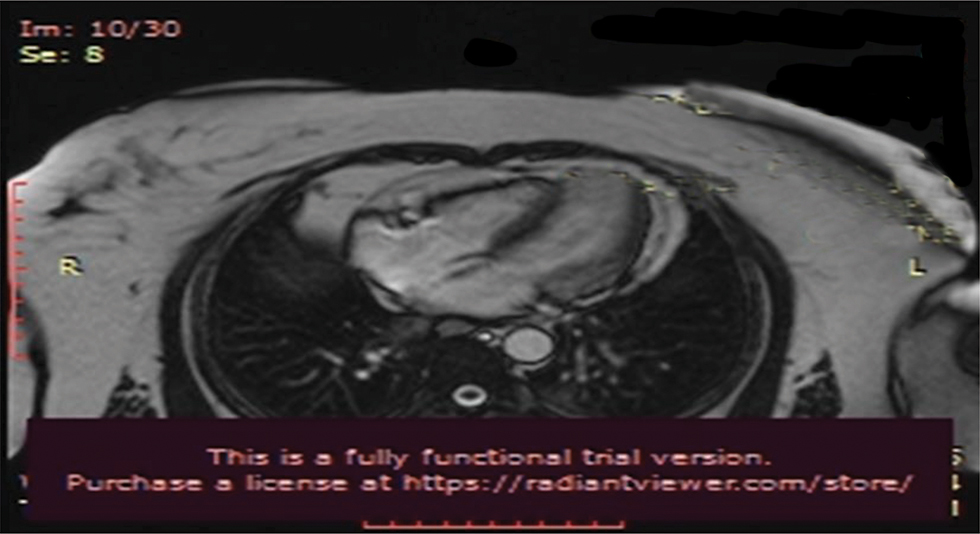

Fig. 8 Cardiac MRI.

Fig. 8 Cardiac MRI.

|

Investigation |

Patient range |

|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; CRP, C-reactive protein; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; INR, international normalized ratio; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PT, prothrombin time; SGOT, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase; SGPT, serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase; VLDL-C, very low density lipoprotein cholesterol. |

|

|

Hb (gm/dl) |

13.4 |

|

Total leucocyte count (per ul) |

11,600 |

|

Thrombocytes (per ul) |

3,60,000 |

|

Na/K (mmol/L) |

139/4.7 |

|

Creatinine/blood urea (mg/dl) |

0.7/16 |

|

Serum total bilirubin/direct (mg/dl) |

0.6/0.3 |

|

SGOT/SGPT (U/L) |

36/28 |

|

Total protein/albumin (gm/dl) |

8/3.9 |

|

PT/INR/aPTT(sec) |

11/1.06/24 |

|

Total blood cholesterol/triglycerides levels (mg/dl) |

152/78 |

|

HDL-C/LDL-C/VLDL-C (mg/dl) |

42/94/18 |

|

High-sensitivity CRP (mg/L) |

5 |

|

ESR (mm /1 hour) |

4 |

|

NT pro brain natriuretic peptide (pg/mL) |

334 |

|

CPK/LDH (U/L) |

1200/998 |

|

Peak troponin T levels |

86 ng/L |

CXR showed normal-sized heart with apex of left ventricular (LV) type (Fig. 1). Normal-sized aorta and pulmonary bay is normal. Pulmonary vascular markings are normal.

ECG was suggestive of normal sinus rhythm, left axis deviation with rS in III, augmented vector foot (aVF), left anterior hemiblock (LAHB), ST depressions in I, augmented vector right (aVL), V2-V4 (Fig. 2).

2D Echo

No regional wall motion abnormalities (RWMA), good biventricular function, grade I diastolic dysfunction, no mitral regurgitation (MR)/aortic regurgitation (AR)/tricuspid regurgitation (TR)/pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH), and no pulmonary embolism (PE)/vegetation (VEG)/clot.

Laboratory Parameters

Except for elevation of cardiac enzymes and NT pro BNP, the rest of the reports were normal.

Coronary Angiogram

CAG (shown in Figs. 4, 5, 6) was done, and it was suggestive of normal epicardial coronaries. Normal coronary angiogram rules out plaque disruption, spontaneous coronary dissection, coronary thrombus, and embolism. Coronary reactivity testing is further required to confirm the coronary spasm/microvascular dysfunction, which is not feasible in our setting.

Cardiac MRI

Cardiac MRI (Figs. 7 and 8) was suggestive of normal study with no late gadolinium enhancement. It ruled out viral myocarditis and Takutsubo cardiomyopathy.

Clinical Diagnosis

Non-ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI) with elevated troponin and other cardiac enzymes and coronary angiogram suggest normal coronary arteries, with normal cardiac MRI ruling out myocarditis and Takutsubo cardiomyopathy, which makes MINOCA the most possible diagnosis, possibly second to epicardial coronary spasm/coronary microvascular dysfunction.

Patient was started on calcium channel blocker dilzem, which showed significant improvement, and her frequency of using sublingual nitrates was reduced.

Conclusion

There are no current appropriate management guidelines established for identification of the underlying causes of MINOCA; hence, it remains a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for clinicians. Also, availability of coronary reactivity testing is limited in many centers.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Cardiovascular Disease in Women: Clinical Perspectives. Circ Res. 2016;118(08):1273-1293.

- [Google Scholar]

- ESC working group position paper on myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(03):143-153.

- [Google Scholar]

- Systematic review of patients presenting with suspected myocardial infarction and nonobstructive coronary arteries. Circulation. 2015;131(10):861-870.

- [Google Scholar]

- Myocardial infarction without obstructive coronary artery disease is not a benign condition (ANZACS-QI 10. Heart Lung Circ. 2018;27(02):165-174.

- [Google Scholar]

- Medical therapy for secondary prevention and longterm outcome in patients with myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2017;135(16):1481-1489.

- [Google Scholar]

- Presentation, clinical profile, and prognosis of young patients with myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA): results from the VIRGO study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(13):e009174.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries on physical capacity and quality-of-life. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120:341-346.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adverse outcomes among women presenting with signs and symptoms of ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease: findings from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) angiographic core laboratory. Am Heart J. 2013;166(01):134-141.

- [Google Scholar]