Translate this page into:

Coronary Artery Disease in Young Females: Current Scenario

Dr. Monica Kher, MBBS, DNB (General Medicine), DNB (Cardiology), FAPVS A-1504, Tower A, Amrapali Platinum, Sector 119 Noida 201301, Uttar Pradesh India monicakher1970@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Women in Cardiology and Related Sciences and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Background Despite coronary artery disease (CAD) being the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in females, women still have been underrepresented in clinical trials. We have abundant data for young males with obstructive CAD, but there is scarcity of data for young females.

Objectives To observe the presentation, disease pattern, risk factors, ventricular function, and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) efficiency in young females in comparison with young males with obstructive CAD who required PCI.

Material and Methods We conducted a hospital-based retrospective study and analyzed the data of young patients (< 45 years of age) who had undergone PCI over the past 2 years. We observed the demographic profile, clinical findings, and investigative and treatment modalities in these patients.

Results Total 200 young patients underwent PCI for obstructive CAD over a span of 2 years. Among these patients, 42 patients were females. In comparison to males, hypertension (43.7% vs. 69.1%, p = 0.008) was more among females, which was statistically significant. Smoking was predominant in young males than young females. Also, males presented as acute ST-elevation MI, whereas females presented with unstable angina or non–ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI). Multivessel involvement, LV dysfunction, success of PCI, and complication rates were similar in both the groups. Anemia was more predominant in females (< 11 g/dL) than in males (< 13 g/dL). Also, complexity of lesion on angiography (B2 or C type of lesions) was greater in females than males, which was statistically significant (p = 0.02).

Conclusion Diabetes, hypertension, and other metabolic factors play a very important role in the onset of CAD in young women. NSTEMI and complex lesions showed greater predominance in females than in males in our study. However, the success and complication rate of PCI remained the same.

Keywords

coronary artery disease

percutaneous coronary intervention

coronary heart disease

myocardial infarction

coronary angiogram

left ventricle

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) remains unrecognized, particularly in young women. In the modern era, women are self-dependent and are well aware of their rights, but unfortunately their awareness and attitude toward their health especially cardiovascular diseases is largely ignored. Though the women constitute 48% of the total population in India, CAD remains a major formidable health problem in women. Indeed, it is rightly said that coronary heart disease (CHD), the most prevalent form of heart disease, is “underdiagnosed, undertreated, and underresearched” in women.1

Various studies on CAD in young patients labeled them as having “premature” CAD, but it is now better understood as a rapidly progressive form of the disease. According to the literature, most patients were males, but with changing scenario of CAD especially in females, the statement requires validation.2

From 1960 to 1995, the prevalence of CAD in adults increased from 3 to 10% in urban Indians and from 2% to 4% in rural Indians, with women having rates similar to men.3 It is estimated that 31% of women will die from CAD, yet approximately 70% of university-educated women consider their risk of CAD to be < 1%. Women have eight times higher risk of dying from heart disease than from breast cancer, yet they fear more of breast cancer and neglect symptoms of heart disease.4

Material and Methods

We retrospectively analyzed the data of young patients (< 45 years of age) who had undergone percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in our institute over the past 2 years. We noted the details of coronary risk factors, type of CAD presentation, coronary angiogram (CAG), and PCI and its outcome. Laboratory investigations in our study included complete blood picture, renal parameters, cardiac enzymes, and lipid profile. Anemia was defined as < 11 g/dL in females and < 13 g/dL in males. Electrocardiographic (ECG) and 2D echo findings were also analyzed. Left ventricular (LV) dysfunction was defined as LV ejection fraction < 50% (both by Simpson's and volume estimation). In CAG, culprit vessel, number of vessel involvement, lesion characteristics like calcium, complexity of lesion, etc. and tortuosity of vessels were analyzed. Immediate results of PCI like success of PCI and complications (including the puncture site complications) were also taken into consideration in our study.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate analysis of categorical variables was performed with the chi-square test, and continuous variables were analyzed by Student's t-test. Correlations among parameters were evaluated by linear regression analysis. Differences were considered significant at p value of < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using Minitab version 17 software.

Results

Out of 200 cases of “young” PCI patients, 42 were females (M:F::3.76:1). Hypertension was present in 29 (69.1%) females versus 69 (43.7%) males, diabetes mellitus in 14 (33.3%) females versus 36 (22.8%) males, and smoking in 2 (4.8%) females versus 75 (47.5%) males. Five female patients had early menopause, and rest of them were in premenopausal stage. Hypertension, diabetes, and anemia were more prevalent in young females than young male CAD patients (Table 1). Females with CAD were younger than males (p = 0.03).

|

Parameters |

Females |

Males |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Number |

42 |

158 |

– |

|

Age (y) |

37.9 ± 7.3 |

40.5 ± 4.3 |

0.03 |

|

Hypertension |

29 (69.1%) |

69 (43.7%) |

0.008 |

|

Diabetes |

14 (33.3%) |

36 (22.8%) |

0.07 |

|

Smoking |

02 (4.8%) |

75 (47.5%) |

0.00 |

Abbreviation: CAD, coronary artery disease.

Approximately 45.2% of young females presented as acute coronary syndrome (ACS) versus 62.7% of males. Prevalence of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) was more predominant in males than in females (31.1% vs. 19.1%), which was statistically significant (p = 0.03). However, there was no difference in LV dysfunction on echo and number of vessel involvement on CAG (Table 2).

|

Parameters |

Females |

Males |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Presentation (NSTEMI) |

19 (45.2%) |

99 (62.7%) |

0.03 |

|

Presentation (STEMI) |

8 (19.1%) |

49 (31.1%) |

0.03 |

|

LV dysfunction |

10 (23.8%) |

41 (25.9%) |

0.3 |

|

Multivessel |

08 (19.1%) |

35 (22.2%) |

0.57 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; LV, left ventricular; NSTEMI, non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

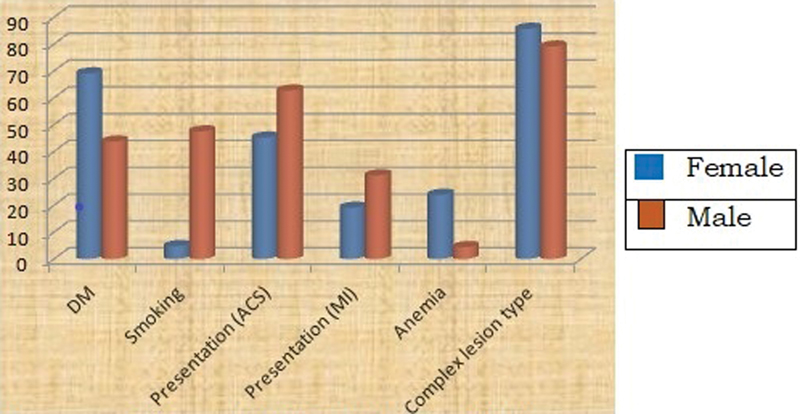

In our study, 53 lesions in 42 female patients and 198 lesions in 158 male patients were treated. Complexity of lesion (either B2 or C) was greater in females, which was also statistically significant (p = 0.02). (Tables 3, 4;Fig. 1).

-

Fig. 1 Bar chart showing the major differences of CAD in young female and male patients (y-axis—percentage, x-axis—different parameters). Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) denotes non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and myocardial infarction (MI) denotes ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

Fig. 1 Bar chart showing the major differences of CAD in young female and male patients (y-axis—percentage, x-axis—different parameters). Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) denotes non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and myocardial infarction (MI) denotes ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

|

Parameters |

Females |

Males |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

No. of lesions |

53 |

198 |

– |

|

No. of lesions per patient |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

|

Lesion complexity (B2 or C) |

36 (85.7%) |

125 (79.1%) |

0.02 |

|

Calcium at lesion |

0 |

2 (1.3%) |

0.16 |

|

Tortuosity of vessel |

1 (2.4%) |

5 (3.2%) |

0.77 |

Abbreviation: CAD, coronary artery disease.

|

Site of lesion |

No. of female cases |

No. of male cases |

|---|---|---|

|

LAD and/or D1 |

32 (60.4%) |

100 (50.5%) |

|

LCx and/or OM |

5 (9.4%) |

35 (17.7%) |

|

RCA and/or PDA, PLV |

14 (26.4%) |

61 (30.8%) |

|

LMCA |

1 (1.9%) |

0 |

|

SVG |

1 (1.9%) |

2 (1.01%) |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; LAD, left anterior descending; LCx, left circumflex artery; LMCA, left main coronary artery; OM, obtuse marginal; PDA, posterior descending artery; PLV, posterior left ventricle; RCA, right coronary artery, SVG, saphenous vein graft.

Even though lesion complexity was found greater in female patients, there was no increased or decreased incidence of any particular coronary artery territory involvement; also there was no difference in success or complication rates between both the groups (Table 5). Because most PCIs were transradial in both the groups, there was no difference in occurrence of local site hematomas.

|

Angioplasty details |

Females (%) |

Males (%) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Success of PCI |

100% |

98.42% |

ns |

|

Complications of PCI |

|||

|

No reflow |

0 |

1 (0.66%) |

0.32 |

|

Acute or subacute stent thrombosis |

1 (2.3%) |

2 (1.3%) |

0.67 |

|

Hematoma at puncture site |

1 (2.3%) |

3 (1.9%) |

0.88 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; ns, not significant; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Discussion

CAD occurring below the age of 45 years is termed as “young CAD.”5 However, various studies considered the age limit varying from 35 to 55 years in the spectrum of young CAD6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 (Table 6).

|

S. No. |

Terminology |

Age group studied |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Young CAD |

< 45 y |

Ericsson et al6 |

|

2 |

Young CAD |

< 40 y |

Konishi et al7 |

|

3 |

Young CAD |

15–39 y |

Gupta et al8 |

|

4 |

Very young CAD |

≤ 35 y |

Christus et al9 |

|

5 |

Premature CAD |

Men ≤ 45 y Female ≤ 55 y |

van Loon et al10 |

|

6 |

Premature CAD |

< 60 y |

Genest et al11 |

|

7 |

Premature CAD |

< 45 y |

Pineda et al12 |

|

8 |

Precocious CAD |

2 case reports of familiar CAD of 29 and 31 y |

Norum et al13 |

|

9 |

Early onset CAD |

< 45 y |

Iribarren et al14 |

Abbreviation: CAD, coronary artery disease.

Regardless of race or ethnicity, CAD is the leading cause of death in women. The worldwide INTERHEART study, a large cohort study of more than 52,000 individuals with myocardial infarction (MI), revealed that the first presentation of CHD in women is approximately 10 years later than men, most commonly after menopause. Even though there is this delay in onset, mortality from CHD is progressing more rapidly among women than men.15 In our study in young population with CAD, females were younger.

According to Iyengar et al (Coronary Artery Disease in the Young [CADY] registry),16 the prevalence of standard coronary risk factors (smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia) is high in premature CAD in India, which is similar to previous case-control studies.17 Women with premature CAD have greater prevalence of metabolic risk factors than men. This study showed women to have more comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity, which are amenable to corrective preventive measures. Smoking among female population was less prevalent. These findings were similar to our observation.

GUSTO IIb (Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Coronary Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes), TIMI IIIB (Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction), and the EuroHeart Survey studies showed that women present more frequently with unstable angina and NSTEMI, whereas men have ACS with STEMI.18 19 20 It has been shown that women are less likely to undergo reperfusion therapy after ACS.21 22 In our study also, women had NSTEMI more frequently as compared with men.

Arzamendi et al in their autopsy series observed that among young individuals who died of CAD, three-vessel disease was observed in 39.7% of cases. Moreover, among the whole population < 40 years old, at least one significant coronary lesion was observed in 39.5% of cases, irrespective to the cause of death.23 Indeed, when a rigorous intravascular ultrasound-based investigation was undertaken in a cohort of recently transplanted hearts (mean donor age 33.4 ± 13.2 years) by Tuzcu et al,24 the prevalence of disease was more, with one in six teenagers manifesting with coronary lesions. Even in our study, females had multivessel involvement.

Diabetes and hyperlipidemia are also frequently present in young CAD patients.25 26 Young women with CAD comprise an especially interesting group even though there is the protective effect of estrogen, but predictive factors in this distinctly unusual cohort is poorly understood. In the present study, diabetes mellitus (DM) was more prevalent in females than in young males, but that was not statistically significant.

According to previous studies, hypertension and lack of exercise are both firmly established risk factors for CAD, but they appear to contribute only marginally in young adults. On the contrary, in our study, hypertension was more prevalent in young females (69.1%) than young males, which was significant statistically.

In young males, smoking is considered as a strong risk factor for CAD. According to the Framingham study, repeated exposure to cigarettes and the resulting frequent catecholamine surges damage endothelial cells, leading to dysfunction and injury to the vascular intima.27 In our series, smoking was less in females, so metabolic factors played an important role in female CAD. Women who smoke have a quantitatively similar risk as men,28 but more than five times the risk of nonsmoking women.29 Smoking in combination with oral contraceptives poses a 13-fold increase in CAD mortality.30

Truncal obesity and increased body mass index (BMI) have recently been proposed as potential independent risk factors, particularly in young women with CAD. Sagittal abdominal diameter to skin fold ratio seems to be a good indicator in predicting premature CAD, even better than BMI and waist circumference.31

Presence of calcium at lesion site and tortuous vessels are features of elderly but in a subgroup analysis of the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, high objective hostility scores were associated with the presence of coronary artery calcification. However, the interaction between a genetic propensity to form vulnerable plaque combined with acute stress and/or an active infectious/inflammatory process needs further study.32

Huang et al in their study showed that left main, left anterior descending, and bifurcation lesions were more common whereas type C lesions and right coronary lesions were less common in young female CAD group than in young male CAD group (p < 0.01–0.05). The average lesion length in female patients was significantly longer than that in male patients ([20.36 +/− 13.37] mm vs. [23.04 +/− 13.86] mm, p < 0.05).33 In this study also, complexity of lesion was greater in young female CAD patients, but there was no involvement of any particular coronary territory.

In females, one of the mechanisms of acute presentation is spontaneous coronary artery dissection in 35 to 40 years age group. The patients are divided into three groups: peripartum, atherosclerotic, and idiopathic groups.34 Dissection occurs in tunica intima of the coronary arteries, and the blood penetrates and results in intramural hematoma in tunica media, resulting in restriction in the size of lumen leading to reduction in blood flow and MI. However, we have not encountered any coronary dissections in our young females who presented with MI in our study.

Mortality after an acute coronary event is two times higher in women than in men aged < 50 years.35 36 The cause of increased incidence of adverse event in women with premature CAD is still unknown.

Major limitation of our study was that we analyzed only the young patients who underwent PCI, which means that the incidence of coronary obstructive lesions in the real world is even higher. Second, all these patients belong to single ethnic Asian population. Also, only the conventional risk factors were included, but the other risk factors specific for females as suggested by Jairath N., such as depression and thyroid function, were not taken into consideration37 in our study. Sagittal abdominal diameter to skin fold ratio that seems to be a good indicator in predicting premature CAD, even better than BMI and waist circumference, was not taken into consideration in our study.

Conclusion

In our study, metabolic risk factors contributed to CAD in young females. Also, these patients presented with NSTEMI and had complex coronary lesions than young males. However, the success and complication rates of PCI were the same in both the groups.

Our data highlights the potential to prevent cardiovascular disease in women by creating awareness and publicity about the modifiable risk factors, and hence it can create an impact on the future of cardiovascular disease in women in future. Conventional and female-specific risk factors, novel biomarkers, and genetic analysis should be evaluated for better patient outcome and prognosis.

Acknowledgments

We are immensely grateful to Dr. Maddury Jyotsna, Professor, Department of Cardiology, Nizam's Institute of Medical Sciences, Hyderabad, for her unconditional support in research and statistical analysis of data.

We would like to thank Mehul Sathyanarayan for his expertise in formatting and technical editing.

Finally, our special gratitude to our patients and support staff without whom this study would not have been possible.

References

- Premature coronary artery disease in Indians and its associated risk factors. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2005;1(03):217-225.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coronary heart disease epidemiology in India: the past, present and future. Coronary Artery Dis South Asians New Delhi Jaypee. 2001;xx:6-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Angiographic assessment of effects of bezafibrate on progression of coronary artery disease in young male postinfarction patients. Lancet. 1996;347:849-853. (9005):

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term prognosis and clinical characteristics of young adults (≤40 years old) who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention. J Cardiol. 2014;64(03):171-174.

- [Google Scholar]

- Younger age of escalation of cardiovascular risk factors in Asian Indian subjects. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2009;9:28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coronary artery disease in patients aged 35 or less—a different beast? Heart Views. 2011;12(01):7-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prognostic markers in young patients with premature coronary heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 2012;224(01):213-217.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of risk factors in men with premature coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1991;67(15):1185-1189.

- [Google Scholar]

- Premature coronary artery disease in young (age <45) subjects: interactions of lipid profile, thrombophilic and haemostatic markers. Int J Cardiol. 2009;136(02):222-225.

- [Google Scholar]

- Familial deficiency of apolipoproteins A-I and C-III and precocious coronary-artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(25):1513-1519.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic syndrome and early-onset coronary artery disease: is the whole greater than its parts? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(09):1800-1807.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937-952. (9438):

- [Google Scholar]

- Premature coronary artery disease in India: coronary artery disease in the young (CADY) registry. Indian Heart J. 2017;69(02):211-216.

- [Google Scholar]

- Premature coronary artery disease in Indians and its associated risk factors. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2005;1:217-225.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sex, clinical presentation, and outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Global use of strategies to open occluded coronary arteries in acute coronary syndromes GUSTO IIb investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(04):226-232.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcome and profile of women and men presenting with acute coronary syndromes: a report from TIMI IIIB. TIMI Investigators. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30(01):141-148.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of gender on outcomes of acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(12):1466-1469. , A6

- [Google Scholar]

- Gender differences in management and outcome in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome. Heart. 2007;93(11):1357-1362.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous coronary intervention and adjunctive pharmacotherapy in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2005;111(07):940-953.

- [Google Scholar]

- Increase in sudden death from coronary artery disease in young adults. Am Heart J. 2011;161(03):574-580.

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of coronary atherosclerosis in asymptomatic teenagers and young adults: evidence from intravascular ultrasound. Circulation. 2001;103(22):2705-2710.

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnitude and determinants of coronary artery disease in juvenile-onset, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 1987;59(08):750-755.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serum cholesterol in young men and subsequent cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(05):313-318.

- [Google Scholar]

- Latest perspectives on cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease. The Framingham Study. J Cardiac Rehabil. 1984;4:267-277.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation: A Report from the Surgeon General. 1990. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. DHHS Publication No. (CDC) 908416. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;

- [Google Scholar]

- Relative and absolute excess risks of coronary heart disease among women who smoke cigarettes. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(21):1303-1309.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oral contraceptive use, cigarette smoking and myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1985;253:2965-2969.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sagittal abdominal diameter to triceps skinfold thickness ratio: a novel anthropometric index to predict premature coronary atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2013;227(02):329-333.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of hostility with coronary artery calcification in young adults: the CARDIA study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults. JAMA. 2000;283(19):2546-2551.

- [Google Scholar]

- [Clinical characteristics and outcome comparison between young (< or = 45 years) female and male patients with coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention] Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2010;38(03):248-251.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical course and long-term prognosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Am J Cardiol. 1989;64(08):471-474.

- [Google Scholar]

- Presentation, management, and outcomes of ischaemic heart disease in women. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10(09):508-518.

- [Google Scholar]

- Implications of gender differences on coronary artery disease risk reduction in women. AACN Clin Issues. 2001;12(01):17-28.

- [Google Scholar]