Translate this page into:

Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection in Pregnancy: Report of a Rare Case in a Marfan with Bicuspid Aortic Valve

Paolo Masiello, MD Emergency Cardiac Surgery Division, Cardiothoracic and Vascular Department, San Giovanni di Dio e Ruggi D’Aragona University Hospital Piazza Vittorio Veneto 39, Salerno, 84123 Italy paolo.masiello1@virgilio.it

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Background Type A aortic dissection is an emergency with high morbidity and mortality when surgery is not performed. Few cases are described in the literature about aortic dissection during pregnancy. A correlation between pregnancy and aortic dissection is mainly reported in patients with family history and connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan’s syndrome (MS), Loeys–Dietz’s syndrome, and Ehlers–Danlos’s syndromes, and patients with bicuspid aortic valve (BAV); exceptional cases are also described in patients without risk factors.

Case presentation A 22-year-old young woman with MS, ascending aorta dilation, and BAV became pregnant. During labor, she experienced a short-term chest pain with spontaneous resolution. The electrocardiogram (ECG) and cardiac biomarkers were negative for acute coronary artery disease, but no transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) was performed. A caesarean section was performed without complications. After 1 month, a routine TTE showed a chronic ascending aortic dissection involving the aortic arch and supra-aortic vessels. Due to a normally functioning aortic valve, the David operation was performed (sparing aortic valve) with the replacement of the aortic arch and supra-aortic vessels.

Conclusions Aortic dissection is a rare cardiovascular complication that can occur during pregnancy and is associated with very high-risk mortality. We have reported a rare case of undiagnosed type A aortic dissection involving the aortic arch during unplanned pregnancy in patients with BAV and MS, subsequently treated with the David surgery and replacement of ascending aortic arch and supra-aortic vessels. A closer clinical and instrumental follow-up is necessary in this particular group of patients at risk. Awareness of all physicians involved is mandatory.

Keywords

aortic dissection

pregnancy

Marfan’s syndrome

bicuspid aortic valve

Introduction

Type A aortic dissection is a catastrophic surgical emergency with a well-known high morbidity and mortality, even higher when it occurs during pregnancy.1 Current European Society of Cardiology guidelines on heart disease in pregnancy report pregnancy itself and the peripartum period as being at very high risk of developing complications in patients with aortic disease.1 Acute aortic dissection occurs more often during the third trimester due to hemodynamic changes characteristic of this period, such as increased cardiac output, vascular resistance, and water retention.2 3 A correlation between pregnancy and aortic dissection is mainly reported in patients with family history and connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan’s syndrome (MS), Loeys–Dietz’s syndrome, and Ehlers–Danlos’s syndrome, and patients with bicuspid aortic valve (BAV); exceptional cases are also described in patients without risk factors.4 In patients with MS, the risk of developing aortic dissection during pregnancy is approximately 1% when the aortic root is <40 mm and approximately 3% when the aortic root is >40 mm, with an increasing risk compared with aortic size.5

In this case, we reported an undiagnosed type A aortic dissection involving the aortic arch during pregnancy in patients with BAV and MS. This case is unique because there was no surgical indication before the unexpected pregnancy.

Case Presentation

A 22-year-old woman with MS came to our observation for an evaluation of ascending aorta dilation and valve abnormalities. She was a nonsmoker, and no risk factors were reported. She was reported to have a positive family history of aortic dilation . A transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) was performed showing Valsalva sinus ectasia (42 mm), ascending aorta dilatation (38 mm - indexed 2.2 cm/sqm), with a Z-score of 1.47 (Table 1). The aortic valve was bicuspid with left and right coronary cusp fusion without raphe (type 0 according to the Sievers classification),6 and a trivial regurgitation was detected.

|

Pregestational |

28th week of pregnancy |

1 month after delivery |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Annulus |

23 mm |

23 mm |

24 mm |

|

Sinus of Valsalva |

42 mm |

42 mm |

42 mm |

|

Sinotubular junction |

36 mm |

36 mm |

39 mm |

|

Ascending aorta diameter |

38 mm |

38 mm |

52 mm |

|

Z-score |

1.47 |

1.65 |

4.72 |

Several routine TTEs were performed without detection of increased aortic size. A precautionary β-blocker therapy with atenolol 25 mg/day was prescribed to control blood pressure and to avoid further aortic dilation. After 1 year, she became unexpectedly pregnant, and, according to current guidelines of the time, it was considered safe to continue the pregnancy. The electrocardiogram (ECG) and TTE were performed routinely without any increase in diameter, and therefore she continued the pregnancy without complications.

During labor, she had an episode of irradiated chest pain in the neck and epigastrium, which was short-lived and spontaneously resolved. ECG and myocardial necrosis enzymes performed in a peripheral center were negative for acute coronary ischemic disease, but no TTE was performed. Subsequently, an emergency caesarean section (C-section) was performed without any known complications due to the difficult continuation of vaginal delivery.

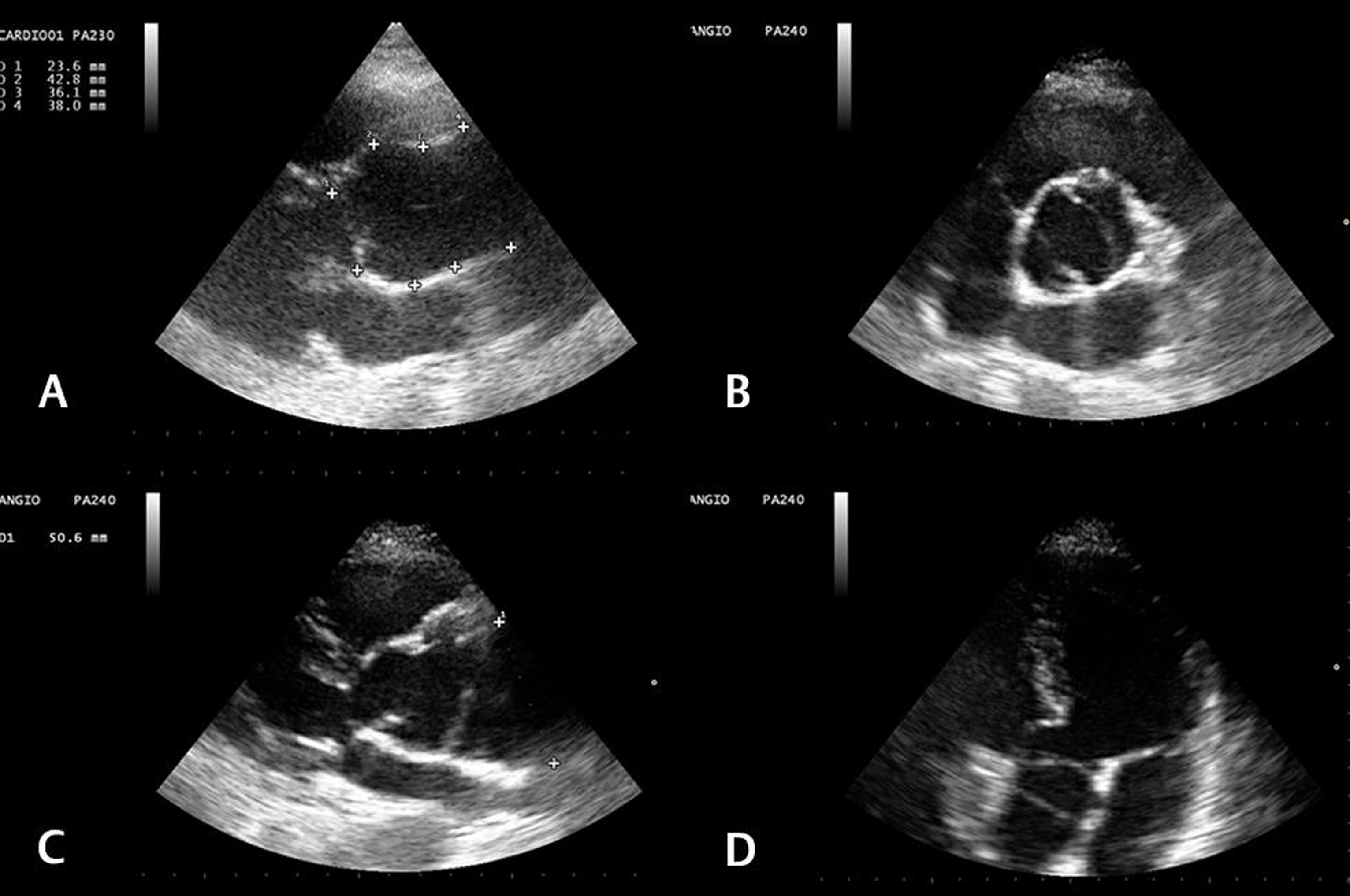

One month later, she underwent a routine follow-up check and a TTE performed showed aneurysmatic dilation of the ascending aorta (52 mm) with chronic dissection involving the aortic arch and supra-aortic vessels (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows the change in aortic dimension before pregnancy and after postpartum recovery. Considering the normal function of the aortic valve, the ascending aorta with aortic arch and supra-aortic vessels were replaced, and the aortic root was preserved by performing a valve-sparing operation (the so-called David operation). This technique involves the removal of the ascending aorta and the root after the detachment of the coronary ostia with the sparing of the native aortic valve. The valve is then reimplanted in a Dacron conduit (Valsalva Gealwave, Cardiva) restoring the cusps; the reimplantation of the coronary ostia on the conduit concludes the operation. The sparing of the aortic valve avoids the implantation of a prosthesis, an important advantage particularly in young patients. The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient was discharged at home on the 10th postoperative day.

-

Fig. 1 (A) Pregestational transthoracic echocardiogram (parasternal long axis view) of the aortic root and ascending aortic aneurysm. (B) Parasternal short axis view of the aortic valve 5 months after delivery. (C) Ascending aortic dissection. (D) Five-chamber view of the aortic dissection.

Fig. 1 (A) Pregestational transthoracic echocardiogram (parasternal long axis view) of the aortic root and ascending aortic aneurysm. (B) Parasternal short axis view of the aortic valve 5 months after delivery. (C) Ascending aortic dissection. (D) Five-chamber view of the aortic dissection.

Discussion

The incidence of aortic dissection in pregnant MS patients, directly related to the increasing size of the ascending aorta, is approximately 1 to 10%.1 Several factors could influence this complication, particularly in the third trimester and in patients with connective disorders, such as hormonal modification, increased cardiac output, and intimate tearing stress due to compression of the abdominal aorta and iliac arteries by the pregnant uterus.7

The increased risk of dissection or rupture of the aorta attributable to pregnancy is about 4 per million pregnancies not only in the population at risk but also in healthy women, as reported by Kamel et al.8

During pregnancy, hormonal modifications induce an alteration of the midwall arteries, with fragmentation of matrix proteins, causing an abnormal response in patients with connective disorders. For this reason, it is difficult to find a safe threshold and it is necessary to have a closer follow-up in these patients at particular risk.3 7

Pyeritz, and Smith and Gros reported a negligible risk of cardiovascular complications in patients with MS and ascending aorta size < 40 mm. In the literature, the risk of dissection and rupture in MS is 1% when the aortic diameter is <40 mm9 10

European guidelines on the management of ascending aortic disease in patients with MS recommend avoiding pregnancy or replacing the ascending aorta before when the aortic diameter is >45 mm or >40 mm if associated with a risk factor.1 Canadian guidelines on the management of aortic disease in patients with MS set the threshold for surgery when the aortic diameter is >50 mm, with a range of 41 to 45 mm in patients considering pregnancy.11

Acute type A aortic dissection is a catastrophic event with 56% mortality if not operated and even higher in pregnancy and in patients with connective tissue disorders. Therefore, the gold standard could be the repair/replacement of the ascending aorta before pregnancy, saving the aortic valve when possible.12

Valve-sparing and ascending aorta replacement eliminate in young women the need for long-term anticoagulation, which is necessary if a mechanical prosthesis is implanted, with a satisfactory long-term prognosis with respect to bioprosthesis degeneration. Patients with a tricuspid aortic valve without significant valvular regurgitation are preferred for this technique, although the 2017 European Valvular Disease Guidelines also identify patients with bicuspid valves, where aortic regurgitation is caused by aortic root enlargement and normal cusp movement (type I) or cusp prolapse (type II),1 as recruitable for this strategy.

In the literature, there are several approaches to treat this disease urgently based on gestational time, such as (1) repairing the ascending aorta with the fetus inside the uterus when the pregnancy is under 28 weeks, (2) performing an urgent C-section after 32 weeks of gestation and immediately after repair/replace the damaged aorta, and (3) performing aortic surgery and C-section simultaneously.2 13 It remains controversial whether to perform a C-section before or repair the ascending aorta when pregnancy is between 28 and 32 weeks.

In Chen et al’s case report, a 28-year-old young pregnant woman at the 16th gestational week underwent a successful surgical replacement of the aorta with an in situ fetus for an acute ascending aortic dissection involving the aortic arch and descending aorta using hypothermic circulatory arrest, highlighting the safety of replacing the damaged aorta even during the second trimester without performing a C-section first.14 When aortic surgery is performed after C-section, it may be useful to insert a balloon into the uterus to prevent postoperative bleeding, as suggested by Zhu et al.13

In our case, the dissection was not diagnosed and the patient was lucky enough to survive such a catastrophic event; we believe that a very strict follow-up conducted by all doctors involved with echocardiography should be performed in pregnant patients with connective tissue disorders, even when guidelines do not suggest an interventional approach.

Acute aortic dissection is a lethal cardiovascular complication in patients with MS during pregnancy that is difficult to treat. The gold standard is aortic repair/replacement before pregnancy, but the abnormal response of patients with connective tissue disorders makes it difficult to find a safe threshold above which to perform surgery.

For these reasons, a closer clinical and instrumental follow-up is needed in this particular group of patients at risk. The awareness of all physicians is mandatory.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Consent to Publish

Written consent to publish this information was obtained from the patient and kept in our database

Availability of Data and Materials

The data generated during this study are not publicly available because of privacy regulation but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

All authors collaborate to write and review the study. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Funding The authors declare that not founding sources were utilized.

References

- 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(34):3165-3241.

- [Google Scholar]

- Retrograde type a dissection in a 24th gestational week pregnant patient - the importance of interdisciplinary interaction to a successful outcome. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;13(01):36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physiological changes in cardiovascular system during normal pregnancy: a review. Indian J Cardiovasc Dis Women WINCARS. 2018;3:62-67/jrn. (2/3)

- [Google Scholar]

- Peripartum type B aortic dissection in patients with Marfan syndrome who underwent aortic root replacement: a case series study. BJOG. 2018;125(04):487-493.

- [Google Scholar]

- A classification system for the bicuspid aortic valve from 304 surgical specimens. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133(05):1226-1233.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute aortic dissection and pregnancy: review and meta-analysis of incidence, presentation, and pathologic substrates. J Card Surg. 2019;34(12):1591-1597.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy and the risk of aortic dissection or rupture: a cohort-crossover analysis. Circulation. 2016;134(07):527-533.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy-related acute aortic dissection in Marfan syndrome: a review of the literature. Congenit Heart Dis. 2017;12(03):251-260.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal and fetal complications of pregnancy in the Marfan syndrome. Am J Med. 1981;71(05):784-790.

- [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Cardiovascular Society. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on the management of thoracic aortic disease. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30(06):577-589.

- [Google Scholar]

- CCS/CSCS/CSVS Thoracic Aortic Disease Guidelines Committee. Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Society of Cardiac Surgeons/Canadian Society for Vascular Surgery joint position statement on open and endovascular surgery for thoracic aortic disease. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(06):703-713.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aortic dissection in pregnancy: management strategy and outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(04):1199-1206.

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful repair of acute type A aortic dissection during pregnancy at 16th gestational week with maternal and fetal survival: a case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7(18):2843-2850.

- [Google Scholar]