Translate this page into:

Psychological Stress in Myocardial Infarction Patients

Daya Vaswani, DM Department of Cardiology, NIMS Punjagutta, Hyderabad, Telangana, 500082 India dayavaswani@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Background The interplay between mental and physical health is an area of inadequate research and hence poorly understood. However, decades of research have made surprising revelations—that both may actually cause each other—but the precise nature of these links is not clearly defined. Hence, the aim of this paper is to determine the prevalence of undiagnosed depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients presenting with Acute Myocardial Infarction (MI) in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of our hospital.

Materials and Methods This is a cross-sectional study conducted on 100 patients admitted with acute MI in the cardiology ICU of our tertiary hospital. A detailed history was obtained, including socioeconomic history and complete medical history. The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) was used to assess subjective psychological stress. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ9) was used to diagnose unrecognized depression, and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD7) was used to identify anxiety disorder among patients.

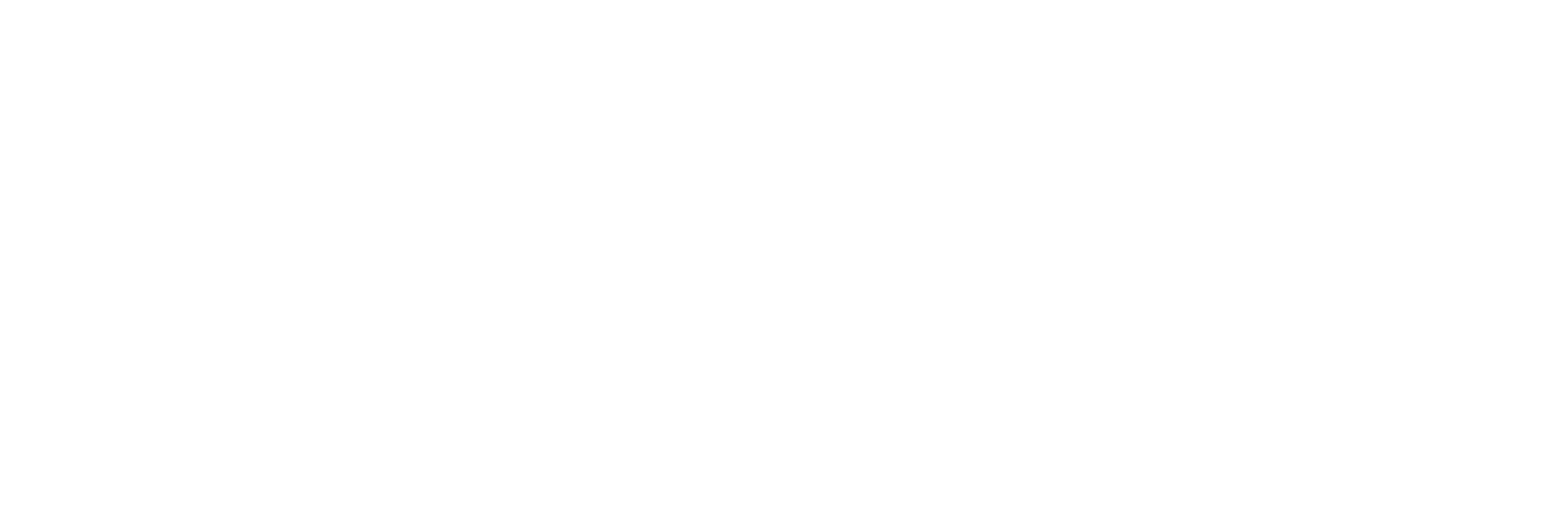

Results Out of total study population, 35% (n = 35) were females (mean age: 57.44 ± 13.54 years) and 65% (n = 65) were males (mean age: 55.90 ± 10.81 years). 82% (n = 82) of the patients were found to have subjective psychological distress, among which 70.73% (n = 58) patients had depressive symptoms, with 5.17% (n = 3) having major depression. Of the total patients diagnosed to have depression, 68.96% (n = 40) patients were males and 31.03% (n = 18) were females, with two out of three patients with major depression being females. Among the total study patients, 24% (n = 24) had anxiety symptoms, out of which 58.3% (n = 14) were males and 41.6% (n = 10) were females, with only two patients categorized as having severe anxiety disorder, both being females. Univariate analysis of study variables with depression showed that increased incidence of subjective psychological stress and lesser physical activity were strongly associated with depressive symptoms (P value: 0.04 and 0.01 respectively). Among the total study patients, 24% (n = 24) had anxiety symptoms out of which 58.3% (n = 14) were males and 41.6% (n = 10) were females, with only two patients categorized as having severe anxiety disorder, both being females. Univariate analysis of study variables with anxiety disorder showed significant association of older age > 60 years (P value 0.002), hypertension (HTN) (P value 0.001), T2DM (P value 0.02), and coexisting T2DM and HTN (P value 0.05), with anxiety disorder. Smoking and alcoholism also demonstrated an independent association with anxiety disorder (P value 0.04 and 0.01 respectively). Lesser physical activity demonstrated a strong association with anxiety (P value 0.0001).

Conclusion The prevalence of psychological stress among MI patients is high, with depression existing in 70.7% of patients, notably, major depression was more in females. Of the total study population, 24% of patients had anxiety, where a severe degree of anxiety was more in female patients.

Keywords

Myocardial Infarction (MI)

psychological stress

depression

anxiety disorder

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), mainly ischemic heart disease, account for a major disease burden globally and is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity.1 2 Affective disorders (mainly depression and anxiety disorders) are among the most common psychological disorders encountered in clinical practice3

Currently, CVD is regarded as the leading cause of global disease burden (GBD), with depression holding fourth place. However, depression is expected to become the second leading cause of GBD by 2020.4 5 A bidirectional relationship exists between depression and coronary heart disease (CHD) that does not involve only bidirectional causation but also common pathophysiology.6 7 8 The causation and association relationship between CHD and anxiety has not been studied as extensively as with depression. Although the association between anxiety and CHD has been known for over 100 years, the exact delineation of this association is lacking.9 10

An intriguing relationship between psychological disorders and CHD appears to exist. Conversely, people suffering from a psychological disorder seem to have an increased risk of CHD, possibly because of a common pathophysiological mechanism linking both diseases. The extent to which each of these psychological disorders jointly and independently contribute to CHD risk should be clarified.11 Hence, the objective of the study is to determine the prevalence and severity of unrecognized depression and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) in patients presenting with acute MI.

Methods

Study Design

This is a cross-sectional study design conducted in the cardiology department of a tertiary institute over a period of 6 months (October 1, 2018 to April 1, 2019).

Study Population

Patients presenting to the ICU with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), including ST Elevation MI (STEMI) and Non-ST Elevation MI (NSTEMI), were included in the study. The diagnosis of Acute MI was made following standard diagnostic criteria.12 Patients were included in the study after obtaining informed consent. Patients with a history of neuropsychiatric disorders or previously treated by a psychologist or psychiatrist were excluded from the study. The study was conducted on a total of 100 patients with ACS.

Study Procedure

The demographic details of all participants were noted. Participants were subjected to a detailed questionnaire in the language that they could speak and understand. Participants were asked about their lifestyle, occupation, and personality using a structured questionnaire that included their response at workplace, introvert or extrovert nature, social behavior, energy level, response to a stressful event, patience, competitive feeling, overthinking, and decision making. Based on their response, patients were designated as having Types A, B, C, D personality types. Past history of (H/O) Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), hypertension (HTN), cerebrovascular event (CVA), chronic kidney disease (CKD), bronchial asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was noted. Family history of T2DM, HTN, and MI was obtained. History of personal addictions of smoking, alcohol, and tobacco chewing was also obtained. History of alcohol use was assessed by asking each patient if on any typical day they consumed at least one drink for females and two drinks for males, for which they responded as “yes” or “no. Patients who have smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and are still smoking or had quit smoking in the last 12 months were taken as smokers.13

All patients were asked individually for the presence of subjective psychological stress by using item 3 of the PSS and scored on a Likert scale of 0,1,2,3, and 4.14 Scores of 3 and 4 were taken as significant psychological stress. Patients with significant psychological stress were then subjected to separate questionnaires for anxiety and depression. (Table 1).

|

Sr No. |

During last one month, how often you thought or felt a certain way |

Never |

Almost never |

Sometimes |

Fairly often |

Very often |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Courtesy: Cohen S. “Perceived Stress Scale.” Psychology. 1994:1–3. |

||||||

|

1. |

How often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly? |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

2. |

How often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life? |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

3. |

How often have you felt nervous and “stressed”? |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

4. |

How often have you felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems? |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

5. |

How often have you felt that things were going your way? |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

6. |

How often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do? |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

7. |

How often have you been able to control irritations in your life? |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

8. |

How often have you felt that you were on top of things? |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

9. |

How often have you been angered because of things that were outside of your control? |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

10. |

How often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them? |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

The nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was used to establish the presence and to assess the severity of depressive symptoms and major depression (Table 2). PHQ-9 is based on the DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorders and is considered a reliable and valid assessment tool. Patients responded to each question on a scale of 0–3 depending on the frequency of depressive symptoms experienced by them. A total score of 0 to 27 was calculated. The severity of depression was grouped into none (score 0–4), minimal symptoms (score 5–9), and major depression (score 10 or more). Major depression was then subcategorized as mild depression (score 10–14), moderately severe depression (score 15–19), and severe depression (score greater than 20).15

|

Sr No |

Over the last two weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems? (Use “✔” to indicate your answer) |

Not at all |

On several days |

More than half of the days |

Nearly every day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Courtesy: Adewuya A. O., Ola B. A., Afolabi O. Validity of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) as a screening tool for depression among Nigerian university students. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006; 96(1–2):89–93. |

|||||

|

1. |

Little interest or pleasure in doing things |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

2. |

Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

3. |

Trouble falling or staying asleep or sleeping too much |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

4. |

Feeling tired or having little energy |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

5. |

Poor appetite or overeating |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

6. |

Feeling bad about yourself—or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

7. |

Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

8. |

Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed. Or the opposite—being so fidgety or restless that you have been moving around a lot more than usual |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

9. |

Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

The seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire (GAD-7) was used to assess the presence and severity of anxiety symptoms (Table 3). Patients rated the frequency of their symptoms by using a Likert scale of 0–3. A total score of 0–21 was calculated. Anxiety disorder was then categorized as mild (score 0–5), moderate (score 6–10), moderately severe (score 11–15), and severe anxiety disorder (score 16–21).16

|

Sr No |

Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems? (Use “✔” to indicate your answer) |

Not at all |

On several days |

More than half of the days |

Nearly every day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Courtesy: Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al; A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006 May 22; 166(10):1092–7. |

|||||

|

1. |

Feeling nervous, anxious, or on the edge |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

2. |

Not being able to stop or control worrying |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

3. |

Worrying too much about different things |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

4. |

Trouble relaxing |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

5. |

Being so restless that it is hard to sit still |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

6. |

Becoming easily annoyed or irritable |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

7. |

Feeling afraid as if something awful might happen |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical data were expressed as proportions and percentages. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine the study variables associated with the presence or absence of depression and generalized anxiety disorder. P value of less than 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Ethical Clearance

The study was approved by the ethical committee of the institute where the study was conducted. All the participants were explained about the aim and objective of the study and were included in the study after signing informed consent form. Participants were also explained that they can withdraw their consent for the study at any time with no untoward consequences.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics and Medical History of Study Participants

Of the total study population, 35% (n = 35) were females, with a mean age of 57.44 ± 13.54 years, and with 42.85% (n = 15) of the females above the age of 60 years. Of the total participants, 64% (n = 64) were diagnosed cases of HTN and 60% (n = 60) were diagnosed with T2DM, and with 40% (n = 40) of the patients having comorbid T2DM and HTN. Family history of MI was found to be positive in 34% (n = 34) of the patients. History of smoking was positive in 41% (n = 41) of the patients. 48% (n = 48) had a history of regular alcohol consumption while 28% (n = 28) of the patients were found addicted to tobacco chewing. A majority of 72% (n = 72) of the patients were not engaged in adequate physical activity. A significant 82% (n = 82) of the participants were diagnosed to have subjective psychological stress (Figs. 1 2).

-

Fig. 1 Gender distribution.

Fig. 1 Gender distribution.

-

Fig. 2 Demographic characteristics based on gender.

Fig. 2 Demographic characteristics based on gender.

Of the total study population, a significant proportion of males were above the age of 60 years. There was an increased incidence of HTN, T2DM, and coexisting HTN and T2DM among males, which was found to be statistically significant when compared with females. Similarly, personal addictions of smoking, alcohol, and tobacco chewing were more predominant among males compared to females. Males were found to have more subjective psychological stress compared to females (P value 0.01). (Table 4 Fig. 2).

|

Variables |

Females (n = 35) (%) |

Males (n = 65) (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age < 60 years Age ≥ 60 years Mean age |

20 (57.15) 15 (42.85) 57.44 ± 13.54 years |

23 (35.4) 42 (64.6) 55.9 ± 10.81% |

0.73 0.006 |

|

Diagnosed HTN |

14 (40) |

50 (77) |

0.0003 |

|

Diagnosed T2DM |

18 (51.4) |

42 (64.6) |

0.015 |

|

Comorbid T2DM and HTN |

7 (20) |

33 (50.7) |

0.003 |

|

Diagnosed CVA |

7 (20) |

6 (9.2) |

0.84 |

|

Diagnosed CKD |

3 (8) |

11 (17) |

0.16 |

|

Diagnosed asthma |

2 (5.7) |

5 (7.7) |

0.46 |

|

Diagnosed COPD |

7 (20) |

5 (7.7) |

0.68 |

|

Positive history of HTN in first-degree relative |

15 (42.8) |

25 (38.5) |

0.24 |

|

Positive history of T2DM in first-degree relative |

15 (42.8) |

23 (35.4) |

0.34 |

|

Positive history of MI in first-degree relative |

12 (34.3) |

22 (33.8) |

0.22 |

|

Smoking |

7 (20) |

34 (52.3) |

0.003 |

|

Alcohol consumption |

5 (14.3) |

43 (66) |

0.0001 |

|

Tobacco chewing |

3 (8) |

25 (38.5) |

0.005 |

|

Engaged in less physical activity |

24 (68.6) |

48 (73.8) |

0.019 |

|

Significant subjective psychological stress |

28 (80) |

54 (83) |

0.01 |

The prevalence of depressive symptoms in the study population was 58% (n = 58), out of which 53.4% (n = 31) of the study participants had minimal depressive symptoms, 29.31% (n = 17) had mild depression, 12.06% (n = 7) had moderately severe depression, and only 5.17% (n = 3) had severe depression. Two out of three patients with severe depression were females (Table 5). Fig. 3 shows the severity of depression and Fig. 4 shows the depression as per sex-based distribution.

|

Variable |

n (%) |

Males (%) |

Females (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Total number of depressed patients |

58 (58%) |

40 (68.96%) |

18 (31.03%) |

|

Normal |

42 (42%) |

25 (59.52%) |

17 (40.47%) |

|

Level Of depression |

|||

|

PHQ-9 (Score 5–9) minimal symptoms |

31 (53.4%) |

21(36.2%) |

10 (17.24%) |

|

PHQ-9 (Score 10–14) mild |

17 (29.31%) |

13 (22.14%) |

4 (6.8%) |

|

PHQ-9 (Score 15–19) moderately severe |

7 (12.06%) |

5 (8.6%) |

2 (3.4%) |

|

PHQ-9 (Score ≥ 20) severe |

3 (5.17%) |

1 (1.7%) |

2 (3.4%) |

-

Fig. 3 Severity of depression.

Fig. 3 Severity of depression.

-

Fig. 4 Severity of depression based on gender.

Fig. 4 Severity of depression based on gender.

Of the total study population, 58% (n = 58) patients were diagnosed to have depression as per the PHQ-9 score. Among them, 18 patients were females and 40 were males. The incidence of minimal depressive symptoms was higher in males. Also, the incidence of mild and moderately severe depression was significantly higher in males. These findings may be due to disparity in the sample size of males and females in the study population. But out of the three patients diagnosed with severe depression, two were females (Fig. 4). Thus, it can be inferred from the above figure that the severity of depressive symptoms is more in females.

The incidence of depression was found to be significantly higher in males. But this finding may be confounded by the unequal distribution of males and females in the study population. Older age was not found to have a significant association with depression (p = 0.27) (Table 6). In this study, univariate analysis of the association of all known risk factors of MI was done with the presence of depression and it was observed that none of the conventional risk factors of MI demonstrated a statistically significant association with depression. Subjective psychological stress and lesser physical activity increased the odds of depressive symptoms (P value 0.04 and 0.01 respectively) (Table 6). In view of the disproportionate sample size of males and females, gender-wise comparison and multivariate analysis could not be done.

|

Variables |

Depressive Status (n = 58) (%) |

P Value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Depressed (n = 58) (%) |

Normal (n = 42) (%) |

|||

|

Sex |

Males |

40 (68.96) |

25 (59.52) |

0.1 |

|

Females |

18 (31.03) |

17 (40.47) |

0.89 |

|

|

Age |

< 60 Years |

34 (58.6) |

27 (64.28) |

0.45 |

|

> 60 Years |

24 (41.4) |

15 (35.71) |

0.27 |

|

|

HTN |

39 (67.24) |

25 (35.71) |

0.14 |

|

|

T2DM |

33 (56.9) |

27 (64.28) |

0.52 |

|

|

Comorbid HTN and T2DM |

19 (32.76) |

21 (50) |

0.80 |

|

|

History of CVA (H/O) |

5 (8.6) |

8 (19.05) |

0.54 |

|

|

Known CKD |

7 (12.06) |

7 (16.6) |

1.0 |

|

|

Diagnosed asthma |

4 (6.9) |

3 (7.14) |

0.79 |

|

|

Diagnosed COPD |

4 (6.9) |

8 (19.04) |

0.39 |

|

|

Smoking |

21 (36.2) |

20 (47.62) |

0.90 |

|

|

Alcoholism |

21 (36.2) |

27 (64.28) |

0.48 |

|

|

Tobacco chewers |

12 (20.7) |

16 (38.09) |

0.56 |

|

|

Family H/o HTN |

19 (32.75) |

21 (50) |

0.80 |

|

|

Family H/o DM |

19 (32.75) |

19 (45.24) |

1.0 |

|

|

Family H/o MI |

17 (29.31) |

17 (40.47) |

1.0 |

|

|

Engaged in lesser physical activity |

48 (82.75) |

24 (57.14) |

0.01 |

|

|

Significant subjective psychological stress |

51 (87.9) |

31 (73.8) |

0.04 |

|

A total of 24 patients were diagnosed to have generalized anxiety disorder as per GAD-7 scoring system. Out of these, 41.6% (n = 10) patients had mild anxiety symptoms, 33.3% (n = 8) had moderate anxiety, 16.6% (n = 4) had moderately severe anxiety, and 8.3% (n = 2) patients had severe anxiety disorder (both were females) (Table 7 Fig. 5).

|

Variables |

n (%) |

Males (%) |

Females (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Total |

24 (24) |

14 (58.3) |

10 (41.6) |

|

GAD-7 Score 0–5 (mild) |

10 (41.6) |

8 (33.33) |

2 (8.3) |

|

GAD-7 Score 6–10 (moderate) |

8 (33.3) |

5 (20.83) |

3 (12.5) |

|

GAD-7 Score 11–15 (moderately severe) |

4 (16.6) |

1 (4.16) |

3 (12.5) |

|

GAD-7 Score 16–21 (severe) |

2 (8.3) |

0 |

2 (8.3) |

-

Fig. 5 Severity of generalized anxiety disorder

Fig. 5 Severity of generalized anxiety disorder

Among the total patients diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder, 58.3% (n = 14) were males and 41.6% (n = 10) were females. The severity of generalized anxiety disorder was more in females, with 12.5% (n = 3) having moderately severe anxiety. Only two patients in the study population were diagnosed with severe anxiety and both were females. (Table 7 Fig. 6)

-

Fig. 6 Gender distribution of generalized anxiety disorder

Fig. 6 Gender distribution of generalized anxiety disorder

Univariate analysis of study variables with anxiety disorder showed a significant association of hypertension, T2DM, and coexisting T2DM and HTN with anxiety disorder. Smoking and alcoholism also demonstrated an independent association with anxiety disorder. Lesser physical activity and older age increased the odds of anxiety symptoms. The incidence of anxiety disorder was found to be higher in the male population. This observation may be confounded by the higher sample size of the male population under study (Table 8). Gender-wise comparison and multivariate analysis could not be done of disproportionate numbers of males and females under study.

|

Variables |

Anxiety Status |

P Value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Anxiety (n = 24) |

Normal (n = 76) |

|||

|

Sex |

Males |

14 |

51 |

0.001 |

|

Females |

10 |

25 |

0.12 |

|

|

Age |

< 60 Years |

13 |

30 |

0.09 |

|

> 60 Years |

11 |

46 |

0.002 |

|

|

HTN |

13 |

51 |

0.001 |

|

|

T2DM |

17 |

43 |

0.02 |

|

|

Comorbid HTN and T2DM |

10 |

30 |

0.05 |

|

|

History of CVA |

6 |

7 |

0.86 |

|

|

Known CKD |

2 |

12 |

0.14 |

|

|

Diagnosed asthma |

0 |

7 |

0.18 |

|

|

Diagnosed COPD |

4 |

8 |

0.50 |

|

|

Smoking |

10 |

31 |

0.04 |

|

|

Alcoholism |

11 |

37 |

0.01 |

|

|

Tobacco chewers |

6 |

22 |

0.07 |

|

|

Family H/o HTN |

9 |

31 |

0.03 |

|

|

Family H/o T2DM |

8 |

20 |

0.17 |

|

|

Family H/o MI |

8 |

26 |

0.06 |

|

|

Engaged in lesser physical activity |

13 |

59 |

0.0001 |

|

Discussion

Cardiovascular diseases, mainly ischemic heart disease, are the leading cause of GBD. As per the World Health Organization (WHO) 2015 statistics, CVDs account for 17.7 million or 31% of all deaths worldwide. Among these, an estimated number of 7 million deaths are due to CHD. According to data collected from India in 2015 of more than 2.1 million deaths, more than a quarter of all deaths was attributed to coronary artery diseases.2 17 18 19 The main risk factors associated with CHD include diabetes mellitus, HTN, dyslipidemia, and obesity, which themselves are chronic medical conditions requiring lifelong therapy. Other risk factors include old age, male gender, sedentary lifestyle, Type A and D personalities, stress, smoking, and family history of CHD.9

Psychological disorders are also a major contributor to GBD.20 21 According to a recent meta-analysis, 14.3% of total deaths worldwide are attributable to psychological disorders.22 Affective disorders (mainly depression and generalized anxiety disorders) are among the most common psychological disorders encountered in routine clinical practice.3

CVD is the leading cause of GBD worldwide, with depression occupying the fourth position in the queue.4 5 However, with its rapidly rising prevalence, depression is expected to become the second leading cause of GBD by 2020. The WHO report of 2012 estimated that ~350 million people are suffering from depressive symptoms and the figure is still rising.23 According to statistical data, depression is more prevalent among CVD patients than the general population.24 Thus, depression may be regarded as an important risk factor for CVD in the same way as conventional risk factors like diabetes and hypertension probably because of the common pathophysiological mechanism. Furthermore, the worse prognosis is observed in patients with comorbid depression and CVD (including all-cause mortality).25

The relationship between anxiety and CHD is not clearly established.26 Studies suggest that the prevalence of anxiety is more in patients with CVD and may be associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.26 This finding holds across the spectrum of anxiety disorder with generalized anxiety disorder imposing major risk for adverse cardiac events in CHD patients.27 28

Stress is a complex phenomenon that begins from exposure to a stressful event, followed by the individual’s perception of psychological stress induced by that event and the resultant behavioral response to that stressful event, which includes sympathetic stimulation and vagal inhibition. The PSS is a widely used psychological tool to assess an individual’s perception of his life events or situations. Higher scores are known to be associated with depressive symptoms related to current life situations.29 Alkhathami et al., through a study of 368 primary healthcare patients with diagnosed hypertension and diabetes, demonstrated that patients who were aware of their uncontrolled HTN or T2DM had increased levels of perceived stress and this was associated with increased prevalence of depression and anxiety. This feeling had no correlation with objective measures of control like glycated hemoglobin and measured blood pressure. Thus, the presence of subjective psychological stress indicates toward increased prevalence of depression and generalized anxiety disorder in patients with chronic diseases. Also, one cannot underestimate the role that having a first-degree relative with HTN, T2DM, CVD, or any chronic illness has to play on perceived stress, considering the role played by immediate family members in the care of other family members in the Indian setting and the subsequent caregiver burden.30

In our study, 58% of the study population had significant depression even though the majority (48%) was classified as having minimal symptoms and mild major depression. The key risk factors associated with depression being HTN, comorbid HTN and T2DM, positive family history of HTN, T2DM, and CVD, smoking and alcohol consumption, and reduced physical activity. A study that was conducted by Sandra et al. in Nigeria, which included 200 participants, concluded that 59.4% of patients had depressive symptoms, with 16.5% of the patients having major depression. In this study, old age and significant perceived stress were shown to be independently associated with depression, incurring a higher risk of CVD in these patients.30 According to a meta-analysis of 30 prospective studies (n = 893,850) conducted by Wu Q et al. in 2016, individuals with depression have a 30% increased risk of CHD compared to non-depressed persons (RR = 1.30, 95% CI: 1.22–1.40).7 Another meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies (n = 323709) conducted by Gan Y et al. in 2014 has found that depression increased the risk of MI by 31% (adjusted HR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.09–1.57) and that of coronary death by 36% (adjusted HR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.14–1.63) compared to non-depressed persons.31

In our study, 24% of patients were found to have generalized anxiety disorder, with only 1% having severe anxiety, and the key factors associated with anxiety were uncontrolled T2DM and tobacco chewing. According to a meta-analysis conducted by Emdin CA et al. in 2016, anxiety incurs an additional 41% risk of CHD in patients (RR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.23–1.61, P > 0.0001).32 Another meta-analysis of 20 studies (n = 249846), conducted by Roest AM et al. in 2010, analyzed the association between anxiety and incident CHD and they found that anxiety poses an additional risk of 26% for the incident CHD (HR = 1.26, 95% CI: 1.15–1.38, P > 0.0001), independent of demographic characteristics, other conventional risk factors, and health habits.33

Although all these findings are significant, it should be emphasized that high levels of heterogeneity exist among studies related to methodological differences and probably the risk associated with anxiety is not as remarkable as that with depression.34 35 Sensitivity analyses have shown that it is likely that the exclusion of depression (which is highly correlated with anxiety) substantially reduces the risk of CHD or attenuates the relationship between anxiety and adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with CHD.10 28 34 The extent to which both of these psychological disorders jointly and independently contribute to CHD risk still needs to be clarified.

Major depression and anxiety disorder can thus be considered as potential risk factors for ACS. Also, they may be associated with worsened outcomes in these patients. Furthermore, these psychological disorders are associated with worsened quality of life. Also, there is a significant overlap in the risk factors associated with CVD and depression and anxiety disorder, further emphasizing a common pathophysiological mechanism relating to these diseases. Thus, identifying the sets of patients with higher PSS scores and directing them to a psychiatric clinic for earlier diagnosis and treatment might improve the overall outcome for patients with CVD.

Conclusion

The study demonstrates a higher prevalence of depression (70.7%) and anxiety symptoms (24%) among patients presenting with ACS to cardiology ICU. Major depression and severe anxiety were more common in females compared with male patients.

Implementations of the Study

Hypertension and diabetes are two well-established and thoroughly studied risk factors for CVD. The importance of their proper control cannot be underestimated for favorable cardiovascular outcomes. Depression and anxiety have a negative impact on body controls, thus interfering with adequate control of HTN and T2DM and further influencing the manifestations of CVD. On the other hand, the stress of living with chronic medical illnesses and immediate family members with chronic illnesses also poses an additional risk of depression and anxiety. This emphasizes the need to screen all patients living with chronic medical illnesses for depressive symptoms and anxiety disorder and referring these patients to a professional clinical psychologist or psychiatrist at the earliest for integrated care and treatment.

Limitations

The study was conducted on a smaller sample population with a disproportionate number of males and females. Hence, gender-wise comparisons could not be done and multivariate analysis could not be done.

Larger sample size with multicentric trial should be done so as to ascertain the actual relationship between psychological stress and ACS. Because of the cross-sectional design of the study, the duration of symptoms was not studied and long term follow up of patients was not done.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014. World Health Organisation; 2014.

- [Google Scholar]

- The global burden of disease study and the preventable burden of NCD. Glob Heart. 2016;11(04):393-397.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101-2107.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:851-858. 9590

- [Google Scholar]

- Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10(11):e1001547.

- [Google Scholar]

- The interface of depression and cardiovascular disease: therapeutic implications. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1345:25-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depression and the risk of myocardial infarction and coronary death: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(06):e2815.

- [Google Scholar]

- Potential biomarkers for depression associated with coronary artery disease: a critical review. Curr Mol Med. 2016;16(02):137-164.

- [Google Scholar]

- Overt and covert anxiety as a toxic factor in ischemic heart disease in women: the link between psychological factors and heart disease. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:751-758.

- [Google Scholar]

- State of the art review: depression, stress, anxiety, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(11):1295-1302.

- [Google Scholar]

- The intriguing relationship between coronary heart disease and mental disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(01):31-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(18):2231-2264.

- [Google Scholar]

- Harrison‘s principles of Internal medicine. (19th ed). Newyork: Mcgraw Hill Companies; 2015. p. :2726-2732. et al. eds.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States.The Social Psychology of Health. Sage; 1988. p. :31-67. In:

- [Google Scholar]

- Validity of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) as a screening tool for depression amongst Nigerian university students. J Affect Disord. 2006;96:89-93. (1-2)

- [Google Scholar]

- A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092-1097.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ischemic heart disease worldwide, 1990 to 2013: estimates from the global burden of disease study 2013. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(04):455-456.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of stable coronary artery disease by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging: Current and emerging techniques. World J Cardiol. 2017;9(02):92-108.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2017). Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Fact sheet, updated May 2017

- Major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder predispose youth to accelerated atherosclerosis and early cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132(10):965-986.

- [Google Scholar]

- The genetic overlap between mood disorders and cardiometabolic diseases: a systematic review of genome wide and candidate gene studies. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7(01):e1007.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(04):334-341.

- [Google Scholar]

- DEPRESSION: A Global Crisis, World Ment Heal Day, 2012

- Prevalence of depression in patients with type II diabetes mellitus and its impact on quality of life. Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35(03):284-289.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anxiety disorders, hypertension, and cardiovascular risk: a review. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2011;41(04):365-377.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review of the affects of worry and generalized anxiety disorder upon cardiovascular health and coronary heart disease. Psychol Health Med. 2013;18(06):627-644.

- [Google Scholar]

- The anxious heart in whose mind? A systematic review and meta-regression of factors associated with anxiety disorder diagnosis, treatment and morbidity risk in coronary heart disease. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77(06):439-448.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association between perceived stress, multimorbidity and primary care health services: a Danish population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(02):e018323.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening for depressive symptoms among patients attending specialist medical outpatient clinics in a tertiary hospital in southern Nigeria. Psychiatry J. 2018;2018:7603580.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depression and the risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:371.

- [Google Scholar]

- Meta-analysis of anxiety as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118(04):511-519.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anxiety and risk of incident coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(01):38-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Panic disorder and incident coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-regression in 1 131 612 persons and 58 111 cardiac events. Psychol Med. 2015;45(14):2909-2920.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is there cardiac risk in panic disorder? An updated systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;194:38-49.

- [Google Scholar]